CHAPTERS

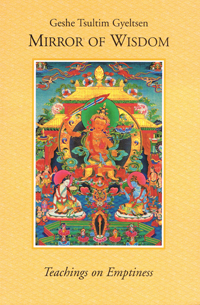

Mirror of Wisdom

Part One: Introduction

Part One: Mind Training - Developing Bodhicitta

Part One: Mind Training - Developing Emptiness

Part One: Learning to Become a Buddha

Part Two: Commentary on the Heart Sutra

THE WISDOM THAT PERCEIVES EMPTINESS

We have already dealt with training our mind in cultivating conventional bodhicitta, or the conventional mind of enlightenment. We now need to look at how to cultivate ultimate bodhicitta-the mind of enlightenment that deals with emptiness. The mind training text we are studying presents actual instructions for cultivating the ultimate awakening mind. In certain texts such as this one, you will find that the conventional mind of enlightenment is presented first and followed by the ultimate mind of enlightenment. In other texts, the order of presentation is reversed. The reason has to do with the mental faculties of Mahayana practitioners. For those with sharp faculties, emptiness is presented first. For those with relatively less sharp faculties the conventional truth is taught before the ultimate.

There are four major traditions within Tibetan Buddhism- Gelug, Kagyu, Nyingma and Sakya. We may find differences between them in terminology or the emphasis of certain practices, but they are all authentic Buddhist traditions. The Kagyu and Gelug traditions use the term mahamudra-"The Great Seal"-to talk about emptiness, whereas the Nyingmapas use the term dzog-chen-"The Great Perfection"-to refer to the same thing. In the Nyingma tradition, there is a tantric practice called atiyoga, which means the pinnacle, or topmost, vehicle. This could be compared to dzog-rim, the completion stage practice of the Gelug tradition, which is the most exalted practice of highest yoga tantra.

When people hear about The Great Perfection of the Nyingmapas they may think that this tradition has something that other Tibetan Buddhist traditions do not, but this is not the case. Each of these traditions is talking about the ultimate nature or reality, which we also call the profound Middle View, or Middle Way. Also, some people might think that because dzog-rim practice is said to be very profound, it must be a quick and easy way to reach enlightenment without having to do meditation. It is never like that. Meditation is as essential in Tantrayana as it is in Sutrayana. It's not as if in tantric practice you just do some rituals, ring the bell-ding! ding! ding!- and then you get enlightened. No; you have to meditate.

As the great Atisha tells us, the way to conduct one's studies of meditation and contemplation in order to realize the true nature of emptiness is by following the instructions of Nagarjuna's disciple, Chandrakirti. Lama Tsongkhapa elucidates the view of emptiness in accordance with the system of Arya Nagarjuna and Chandrakirti. It is within Lama Tsongkhapa's mind-stream that we find the presence of the buddhas of the three times, and I am going to explain emptiness in accordance with Lama Tsongkhapa's way.

WHY DID THE BUDDHA TEACH EMPTINESS?

The historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, taught the profound middle path-the way of the wisdom perceiving emptiness, or selflessness- in order to liberate us from samsara. It is by way of perceiving and experiencing emptiness that we will be able to counteract our basic sense of ignorance, or grasping at self.

There is a passage from the sutras: "Thus, not being able to realize that which is known as emptiness, peaceful and unproduced, sentient beings have been helplessly wandering in different states of cyclic existence. Seeing this, the enlightened one has revealed, or established, emptiness through hundred-fold reasoning." What this tells us is that we ordinary sentient beings, who are unable to see the ultimate nature of everything that exists, create all kinds of negative karmic actions for ourselves and face unwanted problems and sufferings as a result. All the teachings Buddha gave either directly or indirectly point to what emptiness is. This is because the sole purpose of Buddha's teaching is to free all of us from the causes of suffering.

TRUTH AND FORM BODIES

For us to reach the state of enlightenment we need to understand the basis, the path and the result. The basis consists of the two truths, the conventional truth and the ultimate truth. The path is method and wisdom, or skillful means and awareness. The result consists of the two enlightened bodies-the form body, or rupakaya, and the truth body, or dharmakaya. First we must study the view of emptiness as presented by enlightened beings. This is our basis. Then, as trainees on the path, we need to integrate method and wisdom. We must never separate method and wisdom from one another. If we focus on one and forget the other, we are going to get stuck. Eventually, as a result of this practice, each of us will reach the enlightened state and be able to realize the form body and the truth body.

Although nominally different from each other, these enlightened bodies actually share the same nature. For example, Avalokiteshvara, whom Tibetans call Chenrezig, can manifest in innumerable ways to work for sentient beings, yet all these manifestations are Avalokiteshvara. When we become buddhas we will do so in the form of the buddhas of the five families, the five dhyani buddhas. So, you may ask, what happens when I become a buddha, a completely awakened being? Having actualized the form and truth bodies, you will be working solely to help others become free from cyclic existence. You will be constantly working for their benefit until samsara is empty of all sentient beings.

The primary cause for accomplishing the enlightened form body is the practice of method, the collection of positive energy, or merit. The primary cause for accomplishing the truth body is the collection of wisdom, or insight, particularly the wisdom realizing emptiness. This does not mean that accumulating either merit or wisdom alone will allow us to reach the state of enlightenment. When we understand that the wisdom realizing emptiness is the primary cause for the truth body, implicitly we should understand that in order to accomplish that body we must practice method as well.

THE MUTUAL DEPENDENCE OF SUBJECTAND OBJECT

Everything that exists can be classified into objects or subjects. There isn't any phenomenon that doesn't belong to one of these two categories. However, object and subject-the observed and the observer -are actually mutually dependent upon one another. If there is no object, there cannot be an observer of that object. This is what Chandrakirti states in his Supplement to the Middle Way: "Without an object, one cannot establish its perceiver."

There is a line from the mind training text that says, "Consider all phenomena as like a dream." This does not mean that everything that exists is a dream, but that it can be compared to a dream. If you miss this emphasis, then when you read in the Heart Sutra, "no ear, no nose, no tongue" and so forth, you will interpret this passage to mean that those things don't exist at all, which is a totally bizarre notion. This is the position of the nihilist-someone who rejects even the conventional existence of phenomena. We know that the things in our dreams don't really exist, that they are dependent upon our mind. Also, for us to experience a dream, the necessary causes and conditions must come together. First we have to sleep, but if we go into a very deep sleep then we're not going to dream. Just as a dream occurs as a result of certain causes and conditions, such is the case with everything that exists. Every functional phenomenon depends upon causes and conditions for its existence. This is a fact of reality. Nothing exists in and of itself, inherently, or objectively. Everything exists dependently, that is, in dependence upon its parts, and so we say that things are emptyof inherent, or objective, existence.

The next line in the stanza reads: "Analyze the nature of unborn/unproduced awareness." What this means is that this subjective mind, or consciousness, is not born or produced inherently, in and of itself. As much as objective phenomena are to be seen like dreams, which arise from their causes and conditions and are empty of inherent existence, subjective phenomena, too, exist dependently and are empty of inherent existence. We must analyze the non-inherent nature of our awareness, or mind.

With the line, "Consider all phenomena like a dream," we are primarily dealing with the observed, or the object. When we discuss awareness we shift our focus onto the observer, or the subject. If you perceive that objects don't exist independently, or inherently, then what about their subjects? Do they exist inherently? Again, the answer is no. Just like the object, the subject does not exist inherently, in and of itself. Just as objects and their perception exist dependently, so does the person who is experiencing and interacting with the objects and perceptions. The observed and the observer are both empty of inherent existence.

INTELLECTUAL AND INNATE FORMS OF IGNORANCE

Ignorance is the grasping at inherent existence, especially the inherent existence of the self. There are two forms, the intellectual and the innate. The intellectual form of ignorance-grasping at the inherent existence of "I," or self-is found in those whose minds have been affected by some kind of philosophical ideas, but the innate form exists in the mind of every sentient being.

The type of grasping at inherent existence that is presented in the Abhidharmakosha, the Treasury of Knowledge, and its commentaries is the intellectual form. If this were to be taken as the root cause of samsara, then our position would have to be that only those whose minds have been influenced by philosophical concepts could possess the root cause of cyclic existence. According to this view, birds and other animals couldn't have this cause of cyclic existence because they can't study or be influenced by philosophy. It is certainly true that yaks and goats don't sit around discussing philosophy, so they don't have the intellectual form of grasping at self. However, the root cause of samsara exists in the mind-streams of allsentient beings who are trapped in cyclic existence.

The text provides a quote from the Supplement to the Middle Way to clarify this point. "Even those who have spent many eons as animals and have not beheld an unproduced or permanent self are seen to be involved in the misconception of an I." What this passage is telling us is that beings who remain in the animal realm for many lifetimes do not possess the intellectual grasping at self but they do have the innately developed form of ignorance. Therefore, the root cause of cyclic existence cannot be intellectual but must be the innately, or spontaneously, developed ignorant conception that grasps at the self.

INNATE IGNORANCE IS THE ROOT OF CYCLIC EXISTENCE

We need to ask ourselves what the original root cause of cyclic existence is. How did we get here in the first place? Having discovered this cause, we can then apply the method to counteract it. Due to our ignorant attachment to self, we grasp at and get attached to everything that we perceive as being ours and at anything that we think will help to make us happy. This is the root delusion. When we discuss the process of coming into and getting out of cyclic existence- taking rebirth and becoming liberated-we talk about what are known as the twelve links of interdependent origination. In the mind training text, there is a quote that spells out three of these twelve links, which are the main reasons we remain in samsara.

Our innate self-grasping ignorance is the root cause of samsara, so ignorance is the first link. It is because of this ignorance that we create karmic actions, therefore the second link is called karmic formation. This refers not only to bad karmic actions but also includes positive and neutral ones as well. These karmic actions then deposit their latencies upon our consciousness, or mind-stream. Our minds carry the imprints of all the good and bad karmic actions we have created, and when any of these karmic imprints get activated, they can precipitate all the other links and lead to our rebirth either in either a positive or a negative state.

There are six types of sentient beings in cyclic existence. Of these six, three are relatively fortunate types of rebirth and three are unfortunate. Under the influence of ignorance we could create positive karmic actions and, as a result, take one of the good rebirths as a human being, a demigod (asura) or a god (sura). For a positive karmic action to lead to a fortunate rebirth it must be activated by positive conditions. However, even someone who takes a good rebirth is still bound to cyclic existence.

Similarly, under the influence of the delusions of ignorance, attachment or aversion we might create negative karmic actions. These leave imprints on our mental consciousness such that when they are activated by other negative actions or conditioning factors, we can be reborn in one of the three bad migrations. Great negativities precipitate rebirth in the hells. Negativities of medium intensity precipitate rebirth as a hungry ghost. Small negativities can still cause us to be reborn in the lower realms as some kind of animal. Karmic formations connect us to our next conception in our mother's womb, which is the tenth dependent link of existence. These three links of ignorance, karmic actions and existence are very important. To substantiate this point we have a quote from Arya Nagarjuna's Seventy Stanzas on Emptiness, "Actions are caused by disturbing emotions." In other words, the karmic actions we create can be traced back to our innate self-grasping, which is the origin of our disturbing emotions, or delusions. Nagarjuna continues, "Karmic formations have a disturbed nature and the body is caused by karmic actions. So, all three are empty of their own entity." This means that because ignorance, karmic formations and existence all interact with one another to cause our rebirth, they are therefore all empty of inherent existence.

We should train ourselves to clearly ascertain the way in which we enter cyclic existence because then we can work to reverse this process. Once we have put an end to our delusions and contaminated karmic actions we will achieve the state of liberation. This is what Nagarjuna refers to in his Fundamental Wisdom Treatise when he says, "You are liberated when your delusions and contaminated karmic actions are exhausted." We must all understand that any situation we go through is nothing but our own creation-the results of our karmic actions. Usually when things go wrong we find someone else to blame as if others were responsible for our wellbeing. If we can't find other fellow beings to blame then we blame inanimate objects like food. Either way, we always view ourselves as pure and separate from things.

Again, we can use the example of a seed to understand karma. If the seed is not there in the first place, then even if all the other conditions needed for growth are present, we are not going to see any fruit.

MIND TRAINING, DEVELOPING EMPTINESS

In the same way, if we ourselves do not create any good or bad karmic actions, conditioning factors alone cannot bring us any good or bad results. However, once we have created these actions, they can be activated or ripened by other conditions. It is in that sense that other people can act as conditioning factors to activate our good and bad karmic actions. Even the kind of food we eat can be a conditioning factor to activate certain karmic actions we have created. Even so, it is the karmic actions themselves that are the most important factor in bringing good and bad situations upon us. We should adopt positive actions and abandon negative ones because it is us who will experience their results. We should feel that every good and bad experience is the result of our own seed-like karmic actions. This is a very good subject for meditation.

We should understand that the ignorance of grasping at self, which all of us have within our mind-stream, is the very ignorance that locks us like a jailer within the walls of samsara. In the diagram of the wheel of life, which depicts the twelve dependent links, a blind person represents ignorance. We are blind with regard to what we need to abandon in our lives-to what we should not be doing-and also blind to what we need to cultivate in our lives-to what we should be doing. Just as an untrained blind person will create a big mess around himself or herself, so we make a mess of our lives. And we continue doing this, repeating the whole process of samsara and perpetuating a cycle that is very difficult to stop.

We all wish for happiness, but the happiness that we experience is very small. We don't want any kind of pain or problem, but innumerable pains and problems befall us. Deep down we are motivated by the ignorance of grasping at self and engage in different kinds of karmic actions, which bring forth all kinds of experiences. The wisdom that realizes selflessness is the direct antidote to our ignorant self-grasping.

All of us who want to reach the state of highest enlightenment must combine the practice of the two aspects of the path-skillful means, the extensive aspect of the path, and wisdom, the profound aspect of the path-as presented by the two great pioneers of Buddhadharma, Arya Asanga and Arya Nagarjuna respectively. First, we must recognize that the innate ignorance of self-grasping is the root cause of cyclic existence, or samsara. Then we have to deal with the presentation of selflessness, or emptiness, which is the antidote to this ignorance. The Tibetan word, rig-pa, literally means "to see," and ma-rig-pa means "to not see." Ma-rig-pa is translated as "ignorance" while rig-pa is translated as "wisdom." In other words, wisdom directly opposes, or counteracts, ignorance. Rig-pa doesn't just mean any kind of awareness or wisdom-it refers specifically to the awareness, or wisdom, that realizes emptiness.

GRASPING AT SELF AND PHENOMENA

There are two kinds of objects of this ignorant grasping-the grasping at the self of persons and the grasping at the self of phenomena. Both kinds of grasping are misconceptions because the focus of both is non-existent. The grasping at the self of persons means perceiving a person to exist inherently and objectively. This grasping is an active misconception because it is projecting something that doesn't actually exist. The self does not exist in and of itself-it is not inherently existent -however, our innate self-grasping perceives the self, or I, to exist in that manner. Our self-grasping, or ego-grasping, (dag-dzin in Tibetan) actually serves to fabricate the way that the self appears to exist for us. Similarly, grasping at the self of phenomena means that a person perceives phenomena to exist inherently and objectively. There isn't a self of phenomena but our grasping makes one up. It exaggerates and fabricates a self of phenomena and then grasps at its supposed inherent reality. So, we can talk about two kinds of selflessness, the selflessness of a person and the selflessness of phenomena. When we refute the inherent existence of a person, we are dealing with the selflessness of a person, but when we refute the inherent existence of anything else we are dealing with the selflessness of phenomena.

What we mean by "a person" is a projection, or label, that is placed onto the collection of someone's five physical and mental aggregates of form, feeling, discriminative awareness, conditioning factors and consciousness. When we take a person as our basis of investigation and think that this person exists in and of himself or herself, that is what is called "grasping at the self of a person." If we grasp at the inherent existence of the aggregates, that is, at any part of a person, whether it be a part of body or mind, that is called "grasping at the self of phenomena." This is described as including all things from "form to omniscient mind." In Nagarjuna's Precious Garland, it is stated, "So long as the aggregates are misconceived, an I is misconceived upon them. If we have this conception of an I, then there is action that results in birth." What this passage is saying is that as long as we grasp at the physical and mental constituents, or aggregates, as being truly and inherently existent, then we will have the misconception of a truly existent I. Due to this grasping we create karmic actions that precipitate our rebirth and cause us to become trapped again and again within cyclic existence.

The object of our grasping at the self of a person is an inherently existing self. This is something that doesn't exist at all, yet our grasping makes it feel as if that kind of self truly exists and we cling to it in this way. Similarly, the object of the grasping at the self of phenomena is an inherently existent self of phenomena. From these two innate forms of grasping come attachment to the happiness of I. Attachment to one's own happiness actually depends upon the concept of "my" and "mine"-my feelings, my possessions, my body, my family etc. As Chandrakirti states in Supplement to the Middle Way, "At first there arises the conception of and attachment to I, or self, and then there arises the conception of and attachment to mine." We experience the grasping at the self of a person, and this grasping then induces the grasping at the self of phenomena, which is the grasping at mine. Due to the strength of our clinging to these feelings of I, my and mine, we are not able to see the fallacy of seeking self-happiness. This attachment obscures our mind and we are unable to see what is wrong with it.

From being attached to ourselves we become so attached to our things and different parts of our bodies that some of us even change our appearance through plastic surgery. If we weren't attached to our I, we could be totally liberated and free, like Milarepa. He turned a strange greenish color from eating nettles, but this didn't matter to him because he wasn't attached to his appearance. As we look into this mirror of teaching, we can see a different kind of reflection of ourselves-one that shows us how we grasp at things and how attachment arises within us.

It is important for us to understand that "I" and "mine" are not identical. If we can't differentiate between these two, we will have problems later on. The object of our innate grasping at self is the "I" not the "mine," because mine includes the physical and mental aggregates. Chandrakirti explains that if the aggregates of the person were the object of our innate grasping at the self of a person, then we should be able to perceive our aggregates as being I, which we are not able to do. Also, if the aggregates are taken to be the self, then we have to assert that there are five selves because there are five aggregates. The kind of conception that arises with regard to the aggregates is not the conception of I but the conception of mine. We do not think about our ears or our nose as our self, but as things belonging to our self. In the same way, when we investigate our mind, we don't find any part that is I.

We should examine, investigate and analyze the mode of apprehension of our innate grasping at self. In other words, how does our innate grasping perceive the self to exist? What does our innate ignorance perceive? What does it grasp at? We should always focus upon our own condition and not point our finger at someone else's ignorance. Having discovered this, we must then find the means of generating a different kind of perception, one that directly contradicts the mistaken one that grasps at self. This perception is the perfect view of emptiness, or selflessness. However, in order to realize this view, we first have to be clear about what this view actually is. We need to establish the correct view of emptiness.

USING A BASIS TO DESCRIBE EMPTINESS

There is no way to reveal emptiness nakedly or directly because we must use words and terminology. It is only through conventional terms that emptiness can be revealed. In other words, there is no way to discuss emptiness without using something as a basis. For example, when we talk about the emptiness of forms, these forms constitute the basis upon which their emptiness is then established. This is also

the case with any other phenomenon-sound, smell, taste and so forth. Everything around us is characterized by emptiness and so our body or any other phenomenon constitutes the basis upon which we can then understand its emptiness.

In the Heart Sutra we read that "Form is emptiness and emptiness is form." This means that the ultimate nature of form is emptiness and that emptiness relates to form. Emptiness is not the same as form, but in order to understand emptiness we have to take form into consideration as our focal object. Without dealing with a form, we cannot understand its emptiness. There is a line of a prayer that states, "The wisdom gone beyond (emptiness) is beyond words and expression." The Tibetan translation suggests that it is also beyond thought. This means that without depending upon a basis you cannot even conceptualize what emptiness is.

The same thing is stated by Arya Nagarjuna in his Root Wisdom Treatise, where we read, "Without depending upon conventional terms or terminology, one cannot reveal the ultimate truth or reality." When we deal with emptiness, however, it may have nothing to do with form at all. In certain mental states, for example, we don't perceive forms; for instance, when we are in a deep sleep. Even so, it is empty.

When we deal with the selflessness of a person, the basis for that selflessness is the person. Therefore, it is in relation to the person that we establish the person's emptiness. When we deal with a person's aggregates (body, feelings, thoughts, perceptions and so forth), we are dealing with a different kind of basis, one that is the selflessness of phenomena. The text tells us that with regard to what is being refuted, there is no difference in subtlety between establishing the selflessness of a person and establishing the selflessness of phenomena. So, once we understand the selflessness of a person, we don't have to repeat our reasoning over again to understand the selflessness of phenomena. We can simply shift our focus onto another object while remembering the same reasoning with which we realized the selflessness of a person. This is what the great Indian master Aryadeva was saying in his Four Hundred Stanzas on the Middle View when he stated, "The view of an object is the view of everything else."

THE OBJECT OF NEGATION, OR REFUTATION

In order to realize what selflessness or emptiness is, we must first understand its opposite. What is the antithesis of selflessness? What is it that we are trying to refute, or negate, in order to establish what emptiness is? What we are refuting is the way that our innate selfgrasping perceives the self as existing truly, inherently and objectively. Therefore, we say that inherent, objective or true existence of the self is the "object of refutation" or the "object of negation." The object of refutation, or negation, is the thing that we are denying exists. There are a few terms that may sound different from one another but which, in the context of Prasangika-Madhyamaka (the school of philosophy that we are studying here), all mean the same thing. They are "existing by way of its own characteristic," "existing from its own side," "existing in and of itself," "inherent existence," "objective existence", "independent existence" and "true existence." Also, the terms "I," "self" and "person" all mean the same thing.

We can speak about the object of refutation on two levels-the object of refutation by reasoning and the object of refutation by scriptural authority. Inherent existence is the object of refutation by one's own valid reasoning, because nothing exists in and of itself without being imputed by terms and concepts. The object of refutation according to scriptural authority, however, is the grasping at that object, such as the grasping at the inherent, or true, existence of the self. Even though it is an object of refutation, that grasping actually does exist. There is no inherently existent self; however, there is grasping at the self's inherent existence as if it existed inherently. Therefore, the object of refutation by reasoning (inherent existence) refers to something that does not exist, but the object of refutation according to scriptural authority (grasping at inherent existence) refers to something that does exist.

Let us say that we want to investigate the emptiness of a particular form, such as a vase. As we analyze the vase, we must remember that we cannot perceive its emptiness by negating its very existence. Perceiving the vase's emptiness is not the same as concluding that the vase does not exist at all. If we refute, or negate, the conventional existence of the vase, then we have fallen into the extreme position of the nihilist. We have annihilated the vase's very existence and, as a result, we are not going to discover its emptiness. So, if we are not refuting the conventional or nominal existence of form in our search for emptiness, what is it that we are refuting? What is it that doesn't really exist? What we are refuting and what does not exist is the inherent existence of form. If we want to hit a target with an arrow we need to be able to see exactly where that target is. In the same way, to understand what emptiness is, we must be able to precisely identify what it is that is being refuted.

REFUTING TOO MUCH AND NOT REFUTING ENOUGH

If we overestimate the object of negation then we will be refuting too much, but if we underestimate the object of negation we won't be refuting enough. An example of refuting too much is when we take conventional existence and inherent existence to be one and the same, concluding that because phenomena don't exist inherently they must not exist at all. When we take this position we are denying the existence of everything and have become nihilists. Remember, conventional existence and true existence do not mean the same thing.

If we deny the existence of everything then we won't be able to assert the distinction between the two types of phenomena-deluded phenomena (which includes our contaminated karmic actions and delusions, or afflictive emotions) and the liberated aspect of phenomena (which includes the spiritual paths, the true cessation of suffering and so forth). We won't be able to talk about the infallible law of karmic actions and their results because we will be asserting that its existence is merely a hallucination. If we cannot present the existence of both contaminated and uncontaminated phenomena, then we cannot present the complete structure of the path leading to spiritual liberation.

On the other hand, if we underestimate the object of negation and don't refute enough, that is as much of a problem as refuting too much. Certain schools of Buddhism assert only the selflessness of a person and not the selflessness of phenomena. Other schools assert both types of selflessness. Within each of the four schools of Buddhist thought-Vaibhashika, Sautrantika, Cittamatra and Madhyamaka- we find sub-schools. In the Madhyamaka, or Middle Way, school we find two major sub-schools, the Svatantrika-Madhyamaka, or Inference Validators, and the Prasangika-Madhyamaka, or Consequentialists. The Prasangika-Madhyamaka school's presentation of emptiness is considered the most authentic and it is this presentation that we are studying. The schools of Vaibhashika, Sautrantika, Cittamatra and Svatantrika-Madhyamaka all present an assertion of deluded states of mind that we find in Jamgon Kongtrul Yonten Gyatso's Treasury of Knowledge, the root text of which is the Abhidharmakosha.

The Prasangika-Madhyamaka school, however, presents in addition to these delusions, a subtle form of delusion that the other schools have not been able to identify-the conceptual grasping at inherent existence. Except for the Prasangika-Madhyamaka, all the other Buddhist schools assert the inherent existence of phenomena. They assert that if things don't exist inherently, they can't exist at all. The Svatantrika-Madhyamikas, who are in the same school as the Prasangikas, make a distinction between the true existence of phenomena and the inherent existence of phenomena. They say that things do exist inherently, from their own side, but that they do not exist truly. Their explanation for this distinction is that things exist from their own side as well as being posited by thought, or concept. According to them, a phenomenon exists as a combination of existence from its own side and of the mental thought imputed onto it.

They don't include the conceptual grasping at inherent existence as a subtle delusion. Therefore, the Svatantrika-Madhyamaka and other Buddhist schools, apart from the Prasangika-Madhyamaka, have not been able to refute enough in order to establish selflessness or emptiness. In other words, the object of negation identified in their schools is inadequate.

There are many people who try to meditate on emptiness, but I believe that those who really know such meditation are very few. If you overestimate the object of negation and refute too much, you are off track, and if you underestimate the object of negation and don't refute enough, you again miss the point. It's like a mathematical equation. The text cautions us that we have to be very precise in identifying what is to be refuted and refute exactly that amount-no more and no less.

HOW INNATE IGNORANCE PERCEIVES SELF AND PHENOMENA

We have seen how the innate form of ignorance is the root cause of our being in samsara, therefore, we must study how this ignorance perceives or apprehends its object, be it a person, a person's thoughts or a physical thing. Naturally, ignorance apprehends its object in a distorted way, yet how exactly does our innate ignorance perceive things? It perceives things to exist in and of themselves, from their own side, by way of their own characteristics and without being imputed by terms and concepts. However, this is not the way in which things actually exist. In fact, this kind of existence is a complete fabrication.

There is a popular Tibetan children's story that illustrates this point. A lion was always bothering a rabbit, so the rabbit began to plan a way to get rid of him. The rabbit went to the lion and said, "I have seen another beast even more ferocious than you." The lion was outraged by this notion because he felt that he was the king of all the animals. The rabbit said, "Come with me, I'll show you," and took the lion to a lake and told him to look into the water. The lion looked carefully into the water and when he saw his own reflection, he thought it was actually another lion. He bared his teeth at his own reflection but it did exactly the same thing back at him from the water. The rabbit said, "You see that dangerous animal down there? He is the one who is more ferocious than you and if you don't kill him, you won't be the strongest guy in the forest." The lion became even angrier and jumped right into the water. He struggled and splashed for a while but could not find the other lion, so he crawled out onto the bank. The poor lion looked really confused and bedraggled, but the rabbit, laughing to himself, said, "I think you didn't dive deep enough; try again." So, the lion went even deeper into the lake and eventually drowned trying to fight with his own reflection. We have seen that the ignorance of self-grasping is of two kinds- an intellectual form and an innately developed form, and we have established that it is the innate ignorance, the innate self-grasping, that is the root cause of all our problems. So, how does this innate form of ignorance perceive or grasp at I? Without knowing this, even if we try to engage in analytical meditation on selflessness we will never understand it. If a thief has run into a forest, his footprints will be in the forest. If we look for his footprints in the meadow, we will never find the thief.

Also, we must have a clear idea or picture of what inherent or selfexistence is. If the I were inherently existent then how would it exist? Until we can precisely identify the inherent existence of I, we will never be able to realize the absence of the inherently existing I, that is selflessness. It is for that reason that the great bodhisattva, Shantideva, states in his Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life, or Bodhisattvacaryavatara, that until you identify the object of grasping at true existence you won't be able to understand its non-existence; its lack of inherent, or true, existence. Therefore, we need to make a great deal of effort to identify how the I appears to our innate form of ignorance. It is relatively easy for us to understand that we do have this innate grasping at our self but we have difficulty seeing exactly how this grasping perceives the I to exist. Once we are sure that we have found the object of refutation, then in order to realize what emptiness is, we have to refute that object.

We all know that snow is white but it is possible that someone with certain sensory defects will perceive snow as yellow. That is an example of a distorted perception that misconceives the true color of snow. In a similar way, our grasping at self is a distorted perception that misconceives the self to exist in and of itself. The valid perception of snow as white invalidates the perception of snow as yellow. In the same way, our grasping at I is invalidated by the wisdom that perceives selflessness. When we actualize and experience this wisdom, then the grasping at self must leave because we understand that the way in which the self actually exists is the opposite of the way that our self-grasping perceived it.

Through this reasoning, we are trying to establish that the self could not exist in and of itself. As we refute the inherent existence of I, what we are establishing on the other hand is selflessness. If the self does not exist inherently, then how does it exist? It exists being empty of inherent existence. This is how we establish selflessness. We will deal with this topic from different perspectives and angles so that we can really understand it.

The self is apprehended as existing objectively, in and of itself. The example given in the text is a person who is completely ignorant about the fact that the reflection of a face in the mirror is not the real face. Like the lion in the story, such a person cannot tell what is real from what is not real.

WHAT IS SELF?

When someone calls you by your name, by the time you respond there is some kind of concept or picture of yourself that has emerged in your mind. You may not get a very clear or lucid concept of this self, but you do experience some kind of rough imagery of yourself before you answer. This self is something that seems to exist independently of anything else. It's a sort of solid point, a fixed entity that is just there by itself. It's very important for each of us to personally find out where this image of self or concept of I comes from. Does it come from the collection of our body and mind? Or does it come from a single part of our body or mind?

If an I exists then we should be able to find it within either our body or our mind. We have to analyze each part to find where the sense, concept, or image of I comes from. Let's say that your name is John. Who or what is John? You should investigate from the hair of your head down to your toes whether or not any particular part of your body is John. When you have eliminated one part, go on to the next. Then do the same kind of analytical meditation on your mind. Like your body, your mind also has many parts, so you should try to find out whether any one part of the mind can be identified as I. There are many levels or kinds of mind and every one has its preceding and subsequent moments. You have to look at every minor detail and ask yourself, "Is this moment responsible for the sense of I?"

Westerners love to do research; this is a good topic to research. If you feel that your concept or image of I comes out of a particular part of yourself, be it body or mind, then that is what you identify as being your self. You might think, for example, that your sense of I comes from your brain. However, because each aspect of your body and mind has multiple parts, then logically, you must have that many I's or selves within you. Mind is a whole world in itself, with many states and levels. So which one is the self?

At the end of your analytical meditation, you will not be able to pinpoint any part of your body and mind as being an inherently existent I. At this point you might get scared because you haven't found yourself. You may feel that you've lost your sense of identity. There is a vacuity-an absence of something. However, when you really develop certitude of the absence of an inherent I, you should then simply try to remain in that state of meditation as long as you can. As your understanding of the absence of self improves, then outside your meditation sessions you will be able to realize that although the self seemed to exist inherently, this perception was simply the result of your innate grasping. Next time someone calls your name, try to do this examination.

The mind training text states that when we investigate how our innate conception of I apprehends the self to exist, we must make sure that our investigation is not mixed up with the intellectual grasping at self. The text reads, "Detailed recognition of this comes about through cultivating a close relationship with a spiritual friend of the Great Vehicle and pleasing him for a long time." Thus, if we want to comprehend every detail and subtlety of this issue, it is essential that we consistently rely upon a qualified Mahayana guide.

DEPENDENT ARISING

At the end of your analysis it may seem as though no conventional realities or phenomena exist, including the law of karmic actions and results. However, they do exist-they just don't exist in the way that you thought they did. They exist dependently; that is, their existence depends upon certain causes and conditions. Therefore, we say that phenomena are "dependently arising." All the teachings of Buddha are based upon the principle of the view of dependent arising. As Lama Tsongkhapa states in his Three Principal Paths, "…it eliminates the extreme of eternalism." This means that because things appear to your perceptions to exist only conventionally or nominally, their true, or inherent, existence is eliminated. The next line says, "...it eliminates the extreme of nihilism." So, when you understand emptiness you will be able to eliminate the idea of complete nonexistence. You will understand that it is not that things are completely non-existent, it is just that they exist dependently. They are dependent arisings.

In Arya Nagarjuna's Root Wisdom Treatise, he says that there isn't any phenomenon that is not dependently existent, therefore there isn't any phenomenon that is not empty of independent, or inherent, existence. Dependent arising is what we use to establish emptiness. Everything exists by depending upon something else, therefore everything is empty of inherent existence. When we use the valid reasoning of dependent arising we can find the emptiness of everything that exists. For example, by understanding that the self is dependently arising, we establish the selflessness of a person.

An example we could use is the reflection of our own face in the mirror. We all know that the reflection is not the real face, but how is it produced? Does it come just from the glass, the light, the face? Our face has to be there, but there also has to be a mirror, enough light for us to see and so on. Therefore, we see the reflection of our face in the mirror as a result of several things interacting with one another. We can investigate the appearance of our self to our perception in the same way. The self appears to us, but where does this appearance come from? Just like the reflection of the face in a mirror, it is an example of dependent arising.

This is quite clear in the case of functional things such as produced, or composite, phenomena, but there are other phenomena that are not produced by causes and conditions. However, they too exist dependently, that is, through mutual dependence upon other factors. For example, in the Precious Garland, Nagarjuna talks about how the descriptive terms of "long" and "short" are established through mutual comparison. "If there exists something that is long, then there would be something that is short." This kind of existence is dependently arising, but it is not dependent upon causes and conditions. So, dependent arising can mean several things. As we practice analytical meditation on emptiness we need to bring these different meanings into our meditation.

Dependent arising also refers to how everything is imputed by terms and concepts. Everything is labeled by a conceptual thought onto a certain basis of imputation. There is the label, there is that which labels things and then there is the basis upon which the label is given. So, phenomena exist as a result of all these things and the interaction between them. In his Four Hundred Stanzas, Aryadeva says, "If there is no imputation by thought, even desire and so forth have no existence. Then who with intelligence would maintain that a real object is produced dependent on thought?" In the commentary, Mind Training Like the Rays of the Sun, we read, "Undoubtedly, those that exist only through the existence of thought and those that do not exist when there is no thought are to be understood as not existing by way of their own entities, just as a snake is imputed onto a coiled rope." The example I gave earlier is how perceiving snow as yellow is a distorted perception. The example of distorted perception given here is mistaking a coiled rope for a snake.

Several conditions and factors need to come together for a person to misapprehend a coiled rope as a snake. It's not enough just to have a coiled rope in a corner on a bright day. No one is going to be fooled by that. There has to be some obscuration or darkness and distorted perception in the mind as well. Only then can the misapprehension take place. Even if we analyze every inch of that coiled rope we will not find a snake. In the same way, even if we analyze every aspect of self or phenomena we will not find inherent existence.

In the mind training text we find the following explanation. "An easier way of reaching a conviction about the way the innate misconception of self within our mind-stream gives rise to the misconception of self of persons and phenomena is that, as explained before, when a rope is mistaken for a snake, both the snake and the appearance of a snake in relation to the basis are merely projected by the force of a mistaken mind. Besides this, from the point of view of the rope, there is

not the slightest trace of the existence of such an object [as a snake], which is merely projected by the mind. Similarly, when a face appears to be inside a mirror, even a canny old man knows that the appearance in the mirror of the eyes, nose and so forth and the reflection is merely a projection. Taking these as examples it is easy to discern, easy to understand and easy to realize that there is not the slightest trace of existence from the side of the object itself." The moment that a person thinks that there is a snake where the coiled rope lies, the appearance of a snake arises in that person's mind. That appearance, however, is nothing but a projection.

Similarly, although there isn't a self that exists independently and objectively, our grasping misapprehends the self to exist in that way. So then how does the self exist? Like any other phenomenon, the self exists imputedly. It exists by labeling, or imputation, by terms and concepts projected onto a valid basis of imputation. We must be able to clearly distinguish between the imputed self that is the basis for performing karmic actions and experiencing their results, and the inherently existent self that is the object that needs to be negated. When we consider our own sense of self, we don't really get the sense of an imputed self. The feeling we have is more as if the self were existing inherently. Let me explain how the labeling, or imputation, works. People use names for one another but those names aren't the person. The words "John" and "Francis" are merely labels for a person. Just as the reflection of a face in a mirror does not exist from the side of the face, in the same way, the names John and Francis don't exist independently. The names are applied to a valid basis of imputation -that is, the person. When you apply a label onto any base of any phenomenon, it works to define that thing's existence-a vase, a pillar, a shoe and so forth. They are merely labels applied to their respective valid bases of imputation.

There is a common conceptual process involved in labeling things. Things don't exist from their own side, but they are labeled from our subjective point of view and that's how they exist. Let's take the example of a vase that we used earlier. In order to understand the selflessness, or emptiness, of the vase, we need to refute its inherent, true or independent existence, just as we have to refute the inherent, or true, existence of a person in order to understand the selflessness of a person. We must also be able to establish what a vase is conventionally or nominally because we cannot annihilate the conventional reality of a vase.

Conventionally, a vase exists. It is made out of whatever materials were used to create it. It has hundreds and thousands of atoms and then there is its design, the influence of the potter and so forth. All these factors contribute to the production of a vase. So, a vase exists as a mere labeling, or imputation, onto the various factors that form its conventional existence, that is, its valid basis of imputation. If we look for what is being imputed, if we look for "vase," we cannot find it. Just as we cannot find the imputed vase through ultimate analysis, we cannot find the imputed person through ultimate analysis.

The person, self or I is neither the continuity nor the continuum of a person, nor his or her collection or assembly of aggregates. So, what is a person? Chandrakirti gives the example of how the existence of a chariot depends upon the collection of its various parts. In today's terms we could use the example of a car. When we examine a car we discover that no single part is "car." The front wheels are not the car, the back wheels are not the car, neither is the steering wheel or any other part of it; there is no car that is not dependent upon these individual parts. Therefore, a car is nothing but a mere imputation onto its assembled parts, which constitutes its valid basis of imputation. Once the various parts of a car have been put together, the term "car" is imputed onto it. Just as a car is dependent upon its parts, so too is everything else.

Chandrakirti continues, "In the same way, we speak of a sentient being conventionally, in dependence upon its aggregates." So, we should understand that a person also depends upon his or her collection of aggregates. No one aggregate is the person, self, or I, yet there isn't a person who is not dependent upon their aggregates. A person or sentient being is nothing but a label projected onto his or her valid basis. As we find stated in the mind training text, "Such a technique for determining the selflessness of the person is one of the best methods for cognizing the reality of things quickly. The same reasoning should be applied to all phenomena, from form up to omniscient mind."

REFUTING INHERENT EXISTENCE THROUGH VALID REASONING

We need to use our intelligence to establish that the way in which our innate ignorance perceives the self to exist is not really the way that the self exists at all. This is what we call "refuting inherent existence through valid reasoning." It is not enough to say, "Everything is emptiness" or "Things don't inherently exist." We need a process of sound reasoning to back up this viewpoint. Once we have that, we will understand that there isn't anything that exists objectively. However, this is still only an intellectual understanding. We have to develop an intimacy between our perception and the true understanding of emptiness.

When we gain what is known as "definite ascertainment"-certitude with regard to the absence of inherent existence-we will be able to realize emptiness experientially. To substantiate this point, the mind training text offers a quote from the Indian master Dignaga's Compendium of Valid Cognition. "Without discarding this object, one is unable to eliminate it." This is telling us that once we have discovered the object of apprehension of our self-grasping-that is, the inherently existent self-we then need to train our mind to get rid of the idea of this object from our perception.

We must be aware of three examples of mistaken approaches to emptiness. The first example is of people who don't even allow their minds to investigate what self and selflessness are. They just never engage themselves in these questions. People with this kind of attitude will never be able to cultivate the wisdom realizing emptiness because they haven't made any kind of connection with the concept. Again we find a quote from Dignaga's Compendium: "Since love and so forth do not directly counter ignorance, they cannot eliminate that great fault." What this tells us is that even if we cultivate any or all of the four immeasurables-immeasurable love, immeasurable compassion, immeasurable joy and immeasurable equanimity-we still will not be able to understand selflessness. However wonderful these attitudes may be, they do not directly counteract the way in which our innate grasping perceives the self to exist.

The second example is given in another quote from the text: "We acquaint ourselves with a non-conceptual state in which thoughts about whether things are existent or non-existent, whether they are or are not, no longer arise." This refers to people who remain in a blank state of mind during their meditation, without investigating the nature of existence. They stop all kinds of conceptual thoughts. It's almost as if they are in a state of nothingness. Such people also will not understand selflessness, for they have exaggerated the object of refutation and refuted too much. They consider every conceptual thought as if it were the object of refutation; as if to allow a conceptual thought to enter one's mind would be to accept the inherent existence of that thought. They view all thought processes as something to be abandoned. Therefore, they don't think about anything at all. They have confused what is being refuted through valid reasoning-the inherent existence of the self, or I-with something that actually conventionally exists, that is, a thought. In other words, they have taken conventional existence as being identical with inherent existence.

If the wonderful attitudes of love, compassion, joy and equanimity cannot directly counteract our innate self-grasping, how can thinking about nothing achieve this aim? If we stop thinking about anything, that is not a meditation on emptiness because we are not allowing the wisdom understanding emptiness to arise. If we could ever reach the state of enlightenment by this method we would be buddhas without omniscient wisdom or compassion, because we would not have let anything arise in our minds. I encourage you to investigate this for yourselves.

The next example of this mistaken approach to emptiness is, "If, in meditation, following analysis of the general appearance of what is negated, our analytical understanding differs from the meaning intended or we meditate merely on a non-conceptual state in which we do not recognize emptiness, no matter how long we do this meditation, we will never be able to rid ourselves of the seed of the misconception of self." What this is saying is that if we refute inherent existence through valid reasoning and then meditate on something else, our meditation is not going to work. The text continues, "The third mistaken approach is to have established something other than the view of selflessness through analytical awareness so that when we meditate, our meditation is misplaced." We will never realize selflessness with this approach either, because we have disconnected the focus of our valid reasoning from the focus of our meditation. This is, as the text describes, "like being shown the racetrack but running in the opposite direction."

INTERPRETATIONS OF EMPTINESS BY EARLIER MASTERS

In order to realize what selflessness is, we have to understand the self that does not exist. Different schools of Buddhist thought have different interpretations in regard to this. The commentary on one of Lama Tsongkhapa's greatest works, The Essence of Eloquent Presentation on that which is Definitive and that which is Interpretable, tells us that Tsongkhapa asserted that many earlier Tibetan masters, although endowed with many great qualities, somehow missed the true meaning of emptiness. By "earlier Tibetan masters" Tsongkhapa is referring to the period after the eighth century when Acharya Padmasambhava and Abbot Sangharakshita were invited to Tibet and also to the period after the eleventh century, including the arrival of Atisha up until the time of Tsongkhapa in the fourteenth century.

What Lama Tsongkhapa meant was that in terms of the aspect of the path, which has to do with method or skillful means, these masters had innumerable great qualities such as bodhicitta. They had perfected the method aspect of Buddhism, but somehow many of them had missed the view of emptiness. They couldn't quite grasp it completely. Then, in the eleventh century, the great Indian master Atisha was invited to Tibet. He composed a very beautiful text called Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, and with this work Atisha refined the complete teachings of the Buddha, including both sutra and tantra.

In the fourteenth century, Lama Tsongkhapa realized the view of emptiness with the help of the deity, Manjushri. Tsongkhapa said that in order to understand emptiness, our understanding must be free from the two extremes of refuting too much and refuting too little. Some earlier Tibetan masters did not precisely identify the object of refutation. They asserted that the ultimate truth is findable under ultimate analysis. This is a case of underestimating the object of refutation. They have not refuted enough and, in so doing, have missed the view of emptiness. We need to purify much negativity and accumulate great merit in order to realize emptiness. If such great masters can miss it, we can easily miss it as well.

EMPTINESS INDIFFERENT BUDDHISTS CHOOLS

There are four essential points of Buddhism called the "four seals"- every composite phenomenon is impermanent; everything that is contaminated or deluded is suffering in nature; everything that exists is selfless, or empty; and nirvana, or liberation, is peace. All Buddhists accept these four points as definitive teachings, but in regard to the third point-that all phenomena are selfless, or empty-different Buddhist schools have different interpretations.

Theravadins interpret the third seal as meaning only that there is no self of a person. This Buddhist tradition does not accept the selflessness of phenomena. Within the four major tenet schools of Buddhism-Vaibhashika, Sautrantika, Cittamatra and Madhyamaka -we find different assertions and presentations with regard to selflessness, and also in regard to the object of refutation. The two lower schools are the Vaibhashika-sometimes called Particularists or Realists-and the Sautrantika-Followers of Sutra. Like the higher schools, the tenets of these schools say that there isn't a self-sufficient and substantially existent self of a person. However, they also only assert the selflessness of a person and not the selflessness of phenomena.

As we go higher in Buddhist philosophy we find the Cittamatra, or Mind Only, school of thought. Their presentation is different. They talk about two types of selflessness, the selflessness of persons and the selflessness of phenomena. According to the Mind Only school, it is the "duality between subject and object" that is the object of negation or the thing that one is denying exists. They establish the selflessness of phenomena by saying that the subject and its object have the same nature and that it is the division between subject and object as being separate entities that is the object of negation. In other words, the subject and object are empty of being dual and separate entities.

The Mind Only school talks about three different categories of phenomena -"imputed phenomena," which do not exist by way of their own characteristics, and "thoroughly established phenomena" and "dependent phenomena," which do exist by way of their own characteristics.

As mentioned before, in the Middle Way school we find two subschools -the Prasangika-Madhyamaka and the Svatantrika- Madhyamaka. These two philosophical schools present selflessness differently. The Svatantrika-Madhyamaka school also talks about two kinds of selflessness, the selflessness of a person and the selflessness of phenomena. They agree with the Mind Only school that the selflessness of a person is easier to understand than the selflessness of the phenomenal world. They agree with the Mind Only School and the other two Buddhist schools as far as the selflessness of a person is concerned, but their selflessness of phenomena is different.

Most Buddhist schools assert that if something does not exist from its own side or by way of its own characteristics, it does not exist at all. The Svatantrika-Madhyamikas, however, assert that things do exist by way of their own characteristics but do not exist truly. So, according to this school, the terms "true existence" and "existing by way of its own characteristics" are not synonymous. The Svatantrika- Madhyamaka school asserts that everything exists as a combination of projection and inherent existence. They believe that things exist partly as a result of our mind's conceptual projections, or imputations, and partly from their own side. They believe that nothing exists in and of itself without labeling, or conceptual imputation, and this assertion is their object of negation, but they believe that things do exist from their own side to some degree. In other words, phenomena possess a characteristic that we can call objective existence.

In the highest Buddhist school of thought, the Prasangikas, it is said that nothing exists from its own side, even to the slightest extent. Everything is imputed, or labeled. Unlike other schools, they assert that the selflessness of a person does not simply mean that there is no self-sufficient or substantially-existent person. They talk about a person not existing inherently, or in and of itself. According to the Prasangikas, the "emptiness of true existence" and the "emptiness of inherent existence" mean the same thing. Like the Mind Only and Svatantrika-Madhyamaka schools, the Prasangikas assert two types of selflessness, the selflessness of a person and the selflessness of phenomena.

However, in terms of what is being refuted, they assert that there isn't any difference between them. One is just as easy to understand as the other because the process of discovering them is the same. Supposing that you as the meditator want to focus on the selflessness of I, using the person as the basis. When, through reasoning, you perceive the selflessness of I, as you shift your focus onto any other object or phenomenon you can understand the selflessness of that phenomenon by the power of the same reasoning. You don't need to re-establish the selflessness of phenomena using some other method.

For the Prasangika school, there is not even a subtle difference between the selflessness of a person and the selflessness of phenomena.

When we realize that a person exists through mere labeling by terms and concepts and does not exist in and of itself we have realized the selflessness of a person. Taking phenomena as our focus, when we realize phenomena as mere labeling by terms and concepts and not existing in and of themselves, we have realized the selflessness of phenomena. There is a difference with regard to the basis of imputation, but there isn't any difference between the two types of selflessness in terms of what they actually are. It is for that reason that Chandrakirti states that "selflessness is taught in order for sentient beings to be liberated from cyclic existence. The two kinds of selflessness are simply posited on their bases of imputation." When we take a person as the basis of imputation, we are dealing with the selflessness of a person. When we take any other phenomenon as the basis of imputation, we are dealing with the selflessness of phenomena.

According to the Svatantrika-Madhyamikas and the three schools below them, phenomena are not just names or labels. They assert that phenomena should be findable under what is known as "ultimate analysis." When things are found under this type of analysis, they say we can validate the existence of these phenomena. When something is not findable under this kind of analysis, they are not able to assert its existence.

The assertion of the Prasangika-Madhyamaka school is totally different. According to the Prasangikas, nothing should be findable under ultimate analysis. If something is found then that thing must truly exist, and it is true existence, or findability under ultimate analysis, that is the object of refutation according to this school. Arya Nagarjuna said, "Knowing that all phenomena are empty like this and relying on actions and their results is a miracle amongst miracles, magnificence amidst magnificence." So, even though we understand the emptiness of all phenomena, we still rely upon the understanding of the infallible nature of cause and effect.

According to the Prasangika-Madhyamaka school, the terms "existing by way of its own characteristic," "inherent existence" and "true existence" all mean the same thing. For the Prasangikas, all these terms describe the object of negation-the kind of existence that is being refuted or negated. For that reason, our innate grasping at the inherent existence of the self (that is, the innate grasping at the self, existing by way of its own characteristics) is a distorted perception. It is exactly that distorted perception that needs to be cut through and eliminated by cultivating the wisdom that understands emptiness.

THE MEANING OF I, OR SELF, INDIFFERENT BUDDHIST SCHOOLS

All Buddhist schools of thought agree that the I, or self, constitutes the focus of our innate grasping. Where they differ, however, is in terms of what a person is. Certain lower Buddhist schools assert that a person is their five physical and mental aggregates. Other schools say that it's just the mind that is the person and not the other aggregates. In the Mind Only school there is one sub-school that follows a sutra tradition and another that follows reasoning. The sutra followers of the Mind Only school assert that the mind is the person.

The majority of Buddhist schools assert six consciousnesses-the five sensory consciousnesses (eye consciousness, ear consciousness, nose consciousness, tongue consciousness and body consciousness) and mental consciousness. In addition to these six consciousnesses, however, the sutra followers of the Mind Only school talk about "deluded mental consciousness" and "mind basis of all," sometimes translated as "store consciousness." According to them, the mind basis of all is the person and as such it is the focus of the deluded mental consciousness. Those who assert this position say that all our karmic actions deposit their imprints on this particular consciousness.

According to Bhavaviveka, the great Indian master of the Svatantrika-Madhyamaka school, the person is a stream of mental consciousness. So, according to these two schools, when we create karmic actions, the imprints of these actions are stored or deposited on this mind-stream. The reason that the sensory consciousnesses don't store any of these imprints is because they only function here and now. When we die they cease to exist. They are confined to this existence and so cannot become connected to our future lives. Bhavaviveka has presented his position or assertion of what a person is in his work called Blaze of Reasoning.

Now, all the Buddhist schools of thought agree that the person, or self, is an imputed phenomenon-something that is imputed onto its aggregates. Yet, when you ask many of them to pinpoint what that imputed self is, the examples they give are some kind of substantially existent self, or person. Such is the case with some of the assertions we have just been considering. According to the Buddhist school of thought below the Svatantrika-Madhyamaka school, in order to know whether something exists, its existence must be proved by a valid cognition. According to these schools, when we look for a phenomenon it should be findable under analysis. When you find something under such analysis, that thing is said to exist by way of its own characteristics. If you don't find something, then that means that thing doesn't exist at all. However, according to the Prasangika-Madhyamaka school, things should not be findable under ultimate analysis. If you find something, you've gone wrong. That is how the Prasangika position totally opposes that of these other schools.

According to the Prasangika-Madhyamaka school, when you investigate self, you will not find anything such as a person existing from its own side at the end of your analysis. A person is merely a projection that is imputed onto the aggregates. If you do find a person existing from its own side, it should be inherently existent, existing in and of itself, which is impossible because things exist dependently.

THE DIFFICULTY OF UNDERSTANDING EMPTINESS

These are very technical points and you need to take time to think about them. After contemplating the profundity of these teachings, you may simply come to the conclusion that the wisdom realizing emptiness is too difficult to achieve. It is important to understand that however difficult it is, with perseverance and the passage of time, you will be able to see progress within yourself and gain this wisdom. This is simply the law of nature. If we keep doing something, through the power of familiarization, it gradually becomes easier to do.

You may find it very hard even to conceptualize the view of emptiness, especially at the beginning, but think positively and make continuous effort. If you keep inspiring yourself, you can develop what is called an "affinity" with the view of emptiness-an inkling of what it all means, even if you don't yet have a full understanding. You develop a positive doubt about the nature of reality, a question as to whether things actually exist in the way that they normally appear to you. Such positive doubt is somewhat in tune with what we might call the "music" of emptiness and is said to be very beneficial and powerful. The text states that, "Buddha, the transcendent subduer, prophesied that the protector, Nagarjuna, would establish the unmistaken, definitive and interpretable meaning of emptiness as the essence of his teaching." The commentary given on these lines explains that before he spoke on emptiness Buddha knew that ordinary people would find it difficult to understand these concepts. So, even though you may find it very difficult to follow this teaching, you must never give up hope. Determine that you are going to make every effort to understand and please remember that it is better to put your effort into these matters by trying to understand them slowly. After all, if you don't want to suffer any more, you have no choice!

DEFINITIVE AND INTERPRETABLE TEACHINGS

All the teachings of the historical Buddha are contained in the sutras and can be classified into two groups-definitive teachings, which need no elucidation, and interpretable teachings, which require explanation. A definitive teaching is one that can be accepted literally, in the way that Buddha presented it. An interpretable teaching is one that, if it were accepted as it is literally presented, would cause misunderstanding. The Buddha predicted the coming of two great spiritual pioneers, Arya Nagarjuna and Arya Asanga, who would illustrate the real meaning of his teachings and distinguish both their definitive and interpretable nature.

There is a sutra passage that states, "Father and mother are to be killed. The subjects and the country are to be destroyed. Thereby you will attain the state of purity." This passage is obviously an example of Buddha's interpretable teaching, as it requires interpretation. The background to this passage is something that took place in the ancient Indian city of Rajgir, in the present state of Bihar.

Devadatta, a cousin of the Buddha who was always trying to compete with him, befriended a young prince named Ajatashatru. Devadatta poisoned the prince's ears, saying that his father the king was clinging to the throne. He plotted with the prince to have the king assassinated so that Ajatashatru could take his place. Devadatta also plotted to kill the Buddha because he was jealous of Buddha's spiritual attainments. Devadatta told the prince, "I have a beautiful plan. Your father often invites the Buddha and his followers for alms, so you should ask the Buddha and his entourage to lunch. Dig a big fire pit right before the entrance to your palace and cover it so that it's well hidden. Buddha always walks ahead of his monks so, when he steps onto the pit, he will fall in and burn to death." The prince argued that the Buddha was too clever to be deceived, but Devadatta told him that, to be certain, he should poison Buddha's food in case the first plan didn't succeed.

One day, when the king was not at home, the young prince invited Buddha and his monks to the palace for lunch. He constructed a fire pit and poisoned the food just as Devadatta had instructed him. However, when Buddha placed his foot on the hidden fire pit, it instantly turned into a beautiful lake covered with lotus flowers. Buddha and the entire sangha walked safely across the lake on these flowers and entered the palace. The young prince was totally amazed and immediately confessed to Buddha that he wouldn't be able to serve the lunch because it was poisoned. Buddha told him to go ahead and bring the food anyway. When his meal arrived the Buddha blessed it and ate it without any harm coming to him. Meanwhile, the assassins who had been sent by the prince had caught his father.

Before they killed him, the king asked them to take a message back to his son. The message read, "By killing me you have committed two heinous crimes of boundless negative karma because I am your father and an arhat, having already achieved the state of freedom." When Ajatashatru received this message he felt tremendous remorse for his actions. The emotional burden was so great that he felt he would die right then and there. He decided to go to the Buddha and tell him everything. Buddha wanted to give the prince more time to do confession and purification and so he told him, "Father and mother are to be killed and if you destroy the king and his ministers and subjects, you will become a pure and perfect human being."

Of course, at that moment the prince didn't understand the meaning behind the Buddha's statement, but later on when he had given it more thought he realized that the terms "father" and "mother" stood for contaminated karmic actions and delusions and that these were to be killed, or destroyed, within himself. The remainder of the passage meant that other negativities associated with negative karmic actions and delusions also needed to be destroyed in the sense of being purified, and by doing that the prince would be able to attain the state of pure and perfect liberation.

The Heart Sutra is another example of an interpretable sutra, because it contains many statements that require explanation. For example, it doesn't make any sense to say "no ear, no nose, no tongue," and so forth. We know all these things exist. We need to understand that what Buddha really meant by these terms is that the ear, nose and tongue don't exist inherently.

An example of Buddha's definitive teaching is the sutra that presents the "four seals" of Buddhism. As I mentioned before, the four seals are that every composite phenomenon is impermanent, that which is contaminated is suffering in nature, everything that exists is empty, or selfless, and nirvana is peace. This teaching doesn't require any additional interpretation.

When we don't know how to differentiate between the definitive and interpretive teachings of Buddha, we get really confused. The Tibetans say that we make porridge of our misunderstanding. There is a very popular statement from the sutras: "O bhikshus and wise men, you should analyze and investigate my teaching just as a goldsmith analyzes gold. Just as a goldsmith tests gold by cutting it, rubbing it and burning it, so should you examine and investigate my teaching. Do not accept my teaching just out of devotion to me." So, just as a goldsmith tests gold in three ways, so should we examine and analyze the validity of Buddha's teaching through what are known as the "three types of valid cognition."

First, there is "direct valid perception." Then there is "inferential valid perception," which is not direct but based on reasoning. Finally, we use another form of inferential valid perception, which is more like a form of conviction based upon authentic reasoning. Having applied these three kinds of investigation, when we discover the refined goldlike teaching of Buddha, we should then adopt and practice it.

Buddha taught different things to different people at different times and under different circumstances. So, one thing we must do is understand the context of the situation in which he gave the teaching and to whom it was addressed. Without taking all these factors into consideration we cannot understand Buddha's intention. This is why it is important to study both the definitive and the interpretable teachings.