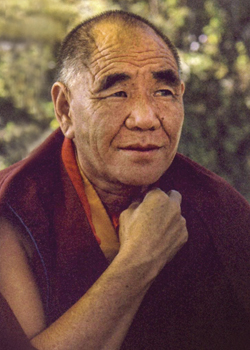

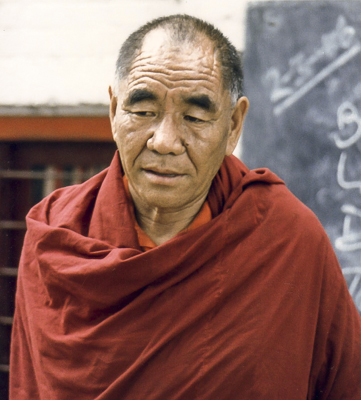

| The essence of the Buddha's 84,000 teachings is bodhicitta: the awakening mind that aspires toward enlightenment, in order to have the perfect ability to free all beings from suffering and lead them to peerless happiness. On his two visits to Singapore in 1997, Venerable Lama Ribur Rinpoche taught extensively on how to generate that precious mind of enlightenment. Rinpoche also gave insightful teachings on lojong (thought transformation), the practice that enables us to transform problems into the causes for enlightenment.

How to Generate Bodhicitta is available as an ebook from online vendors; see links on the Lama Yeshe Wisdom Archive website. |

CHAPTERS

How to Generate Bodhicitta

Preface and Short Biography

The Seven-Point Cause and Effect Instruction

Exchanging Oneself and Others

The second method of generating bodhicitta is that of exchanging oneself with others. The practice of equalizing and exchanging oneself with others combined with the practice of tonglen, or giving and taking, is known as "training the mind" (lojong). If we look at the lineage of these instructions, they began with Buddha Shakyamuni and Manjushri and were handed down from them in an uninterrupted lineage of great masters including Shantideva. The great master Atisha received the lineage from Lama Serlingpa. When Atisha went to Tibet, he taught the seven-point cause-and-effect instruction publicly, and gave the instructions on exchanging oneself with others only to Dromtonpa, because he felt that his other disciples were not fit vessels for such instructions.

Dromtonpa himself kept this lineage very secret—among his many disciples, he gave it only to his spiritual disciple, the foremost Kadampa virtuous friend, Geshe Potowa. Geshe Potowa also kept this instruction very, very secret. Although he too had many disciples, he gave these instructions only to the great Langri Tangpa and Geshe Sharawa. Geshe Langri Tangpa, on the basis of having received and realized these instructions, composed the renowned text, Eight Verses of Thought Transformation. Because these instructions had been put into writing, they became more widespread and many people were able to learn and practice them. Later, the great master Chekawa came to know them. Geshe Chekawa was a scholar learned in all the five sciences but was not satisfied with his knowledge and wished to learn the Dharma. One day he heard two lines of the Eight Verses of Thought Transformation, which said,

Give to others all gain and fortunes,

And take on yourself all loss and defeat.

Geshe Chekawa was intrigued by these lines and wanted to understand how to actually practice giving to others whatever victory and goodness there is and taking upon oneself all loss and defeat. Thus he went in search of these instructions. He traveled to the region of Penbo in Tibet, where Geshe Langri Tangpa lived, but discovered that this great master had already passed away. Fortunately, he met a disciple of Geshe Langri Tangpa, the master Geshe Sharawa, who gave him the complete instructions on exchanging oneself with others. By practicing these instructions, Geshe Chekawa gained the full realization of bodhicitta in his mind. He taught these instructions to many lepers, who were able to cure themselves of leprosy by practicing exchanging oneself with others and tonglen. These instructions thus came to be known as "the Dharma of lepers." Meditating extensively on tonglen, with clear and powerful visualization, is actually the supreme treatment for leprosy.

Geshe Chekawa, thinking that it would be a great loss if these instructions were kept secret, began to teach more publicly the practices of exchanging oneself with others and giving and taking.

The practice of tonglen, giving and taking, is indeed an inconceivably wonderful practice. In the past, when someone was sick, or had a spell cast on him, or was experiencing obstacles of some kind, he would seek the help of a Kadampa lama. The Kadampa lama would do the tonglen practice, taking upon himself both the suffering of the one who was being harmed and the one who was causing the harm, meditating on compassion especially toward the harm-giver. The lama would take upon himself all these sufferings with great compassion, and with great love would give away all virtues and benefits. The Kadampa lamas considered this practice to be the best remedy against spells, obstacles, sickness and so forth.

The instructions on exchanging oneself with others consist of five main points:

1. Equalizing oneself with others

2. The disadvantage of cherishing oneself

3. The advantages of cherishing others

4. The actual thought of exchanging oneself with others

5. The meditation on giving and taking (tonglen)

Equalizing Oneself with Others

At what point should you begin to meditate on the first subject, equalizing oneself with others? Prior to this meditation, you should meditate on the first five steps in the seven-point cause-and-effect instruction: equanimity, recognizing all beings as your mother, remembering their kindness, wishing to repay their kindness, and the affectionate love which sees them as beautiful. Thus you begin to meditate on equalizing yourself with others after having gone through these five steps, which I already explained.

How should you equalize yourself with others? First of all, you need to understand what you mean by "self", when you think in terms of yourself. When we think "myself and others", this "myself" has a sense of great importance, whereas "others" has a sense of much less importance.

So when you think in terms of "me" or "myself", there is a much greater sense of importance than when you think in terms of others. Whatever concerns you becomes extremely significant—whether you feel good or bad, whether you are cold or hot—it is always more important than how others feel. Also, everything related to you—"my body, my possessions, my friends, my family, my kids," everything which is part of your life, yourself—has a much greater sense of importance than the same things related to others—"their bodies, their families," and so forth.

Thinking in this way you can see how you do not regard self and others as equal—you esteem yourself much more than others. However, consider it from the point of view of numbers: you are just one, whereas others are countless. So there is a discrepancy in the way you regard yourself and others: although there are so many more others than yourself, you regard yourself as more important than others. This is completely wrong.

You should decide that your objective in this meditation is to correct this discrepancy and learn to equalize yourself and others. The way to do this is by thinking that you and all other beings are exactly the same in wanting to be happy and free from suffering. You need to think over and over again about the fact that there is not the slightest difference between yourself and others in terms of wanting to be happy and wanting to be free from suffering. In this regard, you and others are exactly the same.

If you compare the instructions of the seven points of cause-and-effect and exchanging oneself with others, the five points of recognizing all beings as mothers, remembering their kindness, wishing to repay their kindness, the extraordinary intention and bodhicitta, are the same. However, there is a difference when we come to the two points of affectionate love and great compassion. The strength of these feelings is different in the two practices. How is that? It is because when you meditate on the kindness of sentient beings according to the seven-point cause-and-effect instruction, you recollect how kind they were when they were your mother, whereas when you meditate according to the instructions on exchanging oneself with others, you recollect their kindness not only when they were your mother but also at other times, when they were not your mother. This meditation is more extensive. Therefore, when you train your mind in the instructions of exchanging oneself with others, the strength of your affectionate love and great compassion will be greater than when training the mind in the seven-point technique of cause-and-effect.

The aim of these instructions is to train your mind in actually exchanging yourself with others, and the way to push the mind in that direction is by contemplating both the faults of cherishing oneself and the advantages of cherishing others. Therefore the next step in the meditation is contemplating the many faults or disadvantages of cherishing oneself.

The Disadvantages of Cherishing Oneself

The sources of these instructions on recognising the disadvantages of the self-cherishing thought or egoism are texts such as Shantideva's Bodhisattvacaryavatara (A Guide to the Bodhisattva Way of Life), and the Guru Puja. There is a verse in the Guru Puja which says:

This chronic disease of cherishing ourselves

Is the cause giving rise to our unsought suffering;

Perceiving this, we seek your blessings to blame, begrudge

And destroy the monstrous demon of selfishness.

A verse from the Bodhisattvacaryavatara says: "All the suffering in the world comes from the desire for one's own happiness" and so forth. In the root text of The Seven-Point Thought Transformation, it says: "Banish the one to blame for everything." This means that all suffering—whatever unwanted problems, obstacles, shortcomings, and sufferings that exist—should be blamed on the self-cherishing thought alone. "All suffering" includes not only the problems that you yourself experience in your life, but from a larger point of view, it also includes wars between countries, disagreements between the leaders of different countries, disagreements at work, arguments within a family such as husband and wife fighting or parents and children fighting, and so forth. All these unwanted experiences come from egoism, the thought of cherishing oneself, and thus they should be blamed on the self-cherishing thought.

As another example of the disadvantages of the self-cherishing thought, let's say you eat too much and get indigestion, and maybe even die from indigestion. Although it may seem that the cause is some kind of digestive ailment, in fact the real cause of the problem is that your self-cherishing mind was not satisfied but wanted more and more food. So you died not from indigestion but due to the self-cherishing thought.

Even in situations where it seems you are not responsible—for example, you are falsely accused of having done something wrong, or you are robbed of your possessions or killed—even in these situations, the cause is the self-cherishing thought. These experiences are the result of your past evolutionary actions [karma] which were motivated by the self-cherishing thought. In past lives, due to egoism, wanting happiness just for yourself, you harmed others, robbed and killed. In this life you are experiencing the results of those actions, therefore those sufferings are to be blamed only on egoism, the self-cherishing thought.

In the past, you were born countless times in the three lower realms, and this too is due to self-cherishing. The self-cherishing thought motivated you to create the causes to experience the sufferings of rebirth as a preta [hungry ghost], as a hell being and as an animal. For example, being born as a preta is the result of miserliness, which in turn comes from egoism, cherishing yourself more than others. Also, if, out of self-cherishing, you point out the physical faults of someone, saying that his face resembles that of an animal, you create the cause to be born as an animal. Therefore, all the sufferings you experienced in countless rebirths in the three lower realms come from nothing other than the self-cherishing thought.

Even from an ordinary point of view, the egoistic self-cherishing thought causes us so much harm. For example, because of holding yourself in high esteem, feeling that you are so great, when you meet someone who seems better than you, you become miserable with envy. When you meet someone who is equal to you, you will want to compete with that person. For example, you could be a businessman who always wants to be on top—that competitive attitude leads to so many problems. Then, when you meet people who are lower than you, you bully them, put them down and point out their faults. All this comes from the self-cherishing thought, feeling that you are so important, so high, so good. Because of these actions you create a great deal of problems in the present as well as the causes for future suffering. Actually, if you really think about all the disadvantages of egoism, the self-cherishing thought, they are inconceivable.

In brief, all the sufferings and difficulties you have encountered from beginningless time until now, all the unwanted experiences in cyclic existence are caused by egoism, the self-cherishing thought. In fact, all the sufferings of cyclic existence are caused both by self-grasping ignorance and the self-cherishing thought. From the philosophical point of view these are two different things, but in the context of mind training they are considered to be the same. On the one hand there is self-grasping—grasping at a true identity, a true I—and on the other hand there is a mind that, instead of letting go of the I, cherishes it, thinking, "I want to be happy, I need this, I need that." That is the self-cherishing thought, and on that basis all suffering, all unwanted experiences and all negativities are generated. Therefore it is the one to blame for everything.

Those of us who practice the Dharma must think continuously over and over again, about the disadvantages of the self-cherishing thought and the advantages of cherishing others—taking care of others rather than oneself. We also need to consider the disadvantages of taking care of this life and the advantages of preparing for the next life. These are things that we need to do.

The Advantages of Cherishing Others

The next point is contemplating the advantages or qualities of cherishing others, or altruism.

This point is clearly stated in the Bodhisattvacaryavatara by Shantideva, which says, "All the happiness of the world comes from altruism." Also, there is a verse in the Guru Puja which says,

I see that cherishing these beings, my mothers,

Is the thought that leads to happiness

And the door leading to infinite qualities.

The root text of the Seven-Point Thought Transformation says, "Meditate on the great kindness of all sentient beings."

On the basis of these quotations you should realize the advantage of cherishing others. For instance, all the happiness of the human rebirth and other fortunate rebirths—having perfect wealth, surroundings, relations and so forth—comes from altruism, cherishing others. Why? Due to cherishing others' lives you abandon killing, and the result of abandoning killing is a fortunate rebirth and also a long life. So having a long life and a fortunate rebirth come directly from having abandoned killing because of cherishing others' lives. Also, having perfect wealth and surroundings is the result of abandoning stealing and practicing generosity, both of which are done on the basis of cherishing others.

In brief, as it says in the Bodhisattvacaryavatara, "There is no need to elaborate more than this; just look at the childish beings who work for their own benefit, and the Buddhas who work for the benefit of others." And there is a verse in the Guru Puja which says, "In short, childish beings work only for their own welfare, while Buddha Shakyamuni acted solely for the benefit of others."

Childish beings act solely for themselves, thinking of their own happiness, in the same way that a child thinks only about himself. On the other hand, the Buddhas became enlightened by cherishing others. Without needing to go into detail, just by looking at the differences between these two types of beings and their actions, we can clearly recognize the differences between self-cherishing and cherishing others.

Consider Buddha Shakyamuni—in the past, since from beginningless time, Buddha Shakyamuni had been like us, trapped in cyclic existence. Then, at some point, He began to cherish others and on the basis of practicing altruism, was able to fulfill the two purposes [of attaining enlightenment and leading others to enlightenment]. Now look at ourselves—because of continuously caring for ourselves alone, cherishing ourselves, we haven't been able to achieve even our own purpose but have been wandering in cyclic existence and the three lower realms again and again since beginningless time. We don't need to go into much detail, just compare the results of Buddha Shakyamuni's actions and our own—one comes from cherishing others and the other comes from egoism, cherishing ourselves. Therefore, by following the self-cherishing thought, no good will come about—only the three unfortunate rebirths.

At this point, Lama Dorje Chang Pabongka would tell stories from the life of Drukpa Kunley, a great meditator of the Drukpa Kagyü tradition who was famous for having an unusual way of speaking which made people laugh.

One day Drukpa Kunley went to Lhasa and paid a visit to the Jokhang, the main temple of Lhasa where you find the Jowo, a very famous statue of Buddha Shakyamuni. Normally, you enter and pay homage to the Jowo, then you circumambulate and take blessings. Drukpa Kunley did this—he circumambulated the statue and took blessings—but then he stood directly in front of the Jowo and said, "In the past you and I were the same, but then you began to practice altruism and to take care of others, so you have become a perfect Buddha. I have been taking care only of myself and I'm still in samsara. Indeed I should now prostrate to you."

Drukpa Kunley was an unconventional yogi; he would express the Dharma truth in a very humorous way. It is said that he once visited the Boudhanath Stupa in Nepal, which has an unusual shape, unlike other stupas which are built in one of eight standard designs. When he arrived at the stupa, he prostrated and said "Although you look like a round heap and unlike one of the eight stupas gone to bliss, I still prostrate to you."

Another time he said, "I've lost three important, precious things." When asked what it was he had lost he said, "One precious thing which I lost is called ignorance, another one is called desire, and the third is called aversion. I have lost these three things which others regard as important and cherish so much." This shows his achievements, but it was expressed in an unusual, funny way. At any rate, Drukpa Kunley was a great adept, and I think that there is a translation of his biography containing all these stories.1

Therefore, we should consider what Buddha Shakyamuni achieved by cherishing others and compare this with the difficulties we are still experiencing because of cherishing ourselves alone. It is very useful to read the stories of Buddha Shakyamuni's previous lives when he was still practicing on the path as related, for example, in the Jataka Tales. These stories show how he performed many incredible deeds in order to cherish others, and thus they can inspire us to practice thought transformation.

It is at this point in the meditation that you reflect on the kindness of sentient beings, both when they were your mothers and when they were not. This reflection becomes very helpful because you realize even more reasons to cherish others rather than to cherish yourself. To give an easy example of the kindness of others when they were not your mothers: the simple fact that we are able to gather in this room and enjoy listening to the Mahayana Dharma is completely due to the kindness of others. Many people put in a great deal of effort so that we can be here. First of all, there may have been another building here that had to be torn down, and that required a number of workers. Then other people worked to design the new building and buy the materials such as bricks, cement and so forth. Other people were needed to operate the machines, since machines don't work by themselves, and to do the actual construction work on the building. Then, when the building was finished, people worked on decorating the interior and collecting the representations of the Buddha's Body, Speech and Mind to place on the altar. Therefore, the fact that we can enjoy coming together here today and listening to the Mahayana Dharma is entirely due to the kindness of others, isn't it?

The same applies to your own home, your belongings, the things you enjoy—all of these are due to the kindness of others. You might say, "No, this is not true. I bought my house with my own money; I bought my clothes with my own money." Yes, that is true, but you earned your money on the basis of others. "Okay, I got the money from others but this is because I worked hard: I did something to receive this money in return." Yes, but the fact that you are able to work is because of others, isn't it? If you think about it carefully, you will see that whatever happiness you now enjoy comes exclusively from the kindness of others.

When you reflect on the advantages of cherishing others, it is very effective to incorporate all these different thoughts. You can also contemplate that all the benefits right up to the attainment of Buddha's state come about because of cherishing others. How is this? If you want to become a Buddha, you must generate the precious mind of bodhicitta, because without bodhicitta, there is no Buddha. The generation of bodhicitta comes about because of the wish to benefit others: "I must achieve the state of Enlightenment in order to benefit others." Also, the exceptional cause of bodhicitta is great compassion, and great compassion comes from cherishing others. Therefore, it is because of others that you generate great compassion.

Furthermore, the practice of the six perfections depends on others. For example, you practice morality in relation to others, and in order to practice generosity and patience you need an object, and these objects are others. It is so true what Shantideva taught in the Bodhisattvacaryavatara, when he says,

Both the Victorious Ones and sentient beings are indispensable to achieving the supreme enlightenment, and since I pay homage to the victors, why don't I pay homage to sentient beings as well?

This is saying that the achievement of supreme enlightenment is half due to the kindness of the Buddhas and half due to the kindness of sentient beings. When we give so much importance to honoring the Buddhas, why don't we give the same importance to honoring the sentient beings who are equally indispensable to our achievement of enlightenment? As the great master Langri Tangpa says in his Eight Verses of Thought Transformation,

I can achieve the supreme state of enlightenment due to the kindness of sentient beings, therefore they are more precious than a wish-fulfilling jewel and I should cherish them to that extent.

There are so many heart-warming instructions on the kindness of sentient beings.

This great master Tangri Langpa was so exceptional, he was truly a superior being. (By the way, he is in the line of the previous incarnations of the late Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche.) It is said that Langri Tangpa was always very serious and smiled only three times in his whole life, so he was known as "Langri Tangpa of the black face" (in Tibetan the term "black face" means "serious"). He spent all of his time meditating on the disadvantages of cyclic existence and bodhicitta, and that is why he didn't find many occasions to laugh.

I'll tell you the story of one of the three occasions when Langri Tangpa laughed and what made him laugh. This story is about his mandala set. In the Kadampa tradition and in the tradition of Lama Pabongka Dorje Chang, the practice of offering the mandala is very much emphasized. When I was young in Tibet, most of us would bring our mandala sets to teachings, so that at the point of offering the mandala very few would be without one. In the row of the tulkus [reincarnated lamas], each tulku would have his own beautiful mandala set—some made of gold, some of silver—but the top would always be of gold. It was quite a scene when all the tulkus offered their mandalas! But that was in the past, and then at a certain point everything was taken away. My own mandala set was taken away. There is also a particular implement used to offer the hundred tormas, which is a kind of flat container decorated with symbols. I had one of these because the Kadampa tradition places so much emphasis on the practice of offering tormas, but that was taken away as well. By "taken away" I mean confiscated by the Communists. Nowadays, I use something very simple.

Anyway, one day Langri Tangpa was meditating, and he had his mandala set on the table next to him. It was probably a simple mandala set, not a beautiful or elaborate one. As he was meditating, he noticed that a mouse had come and was eating some of the grains of his mandala. Among the grains was a big turquoise and for some reason, the mouse was attracted to the turquoise and started to pick at it, trying to get hold of it, but it was too big for him. Then another mouse came and began helping the first one, so both of them were trying to get hold of it. Pretty soon there were five mice and they devised a way to get the turquoise: one mouse laid on his back and held the turquoise on his stomach, and the other four mice held his head and legs and were pulling him along. Langri Tangpa had been watching the mice and when he saw this he broke into a slight laugh. Why did he laugh? Because he thought that in cyclic existence when it comes to fulfilling one's needs, animals are more clever than human beings. It's true, sometimes animals can be smarter than human beings in taking care of the needs and happiness of this life.

The Actual Thought of Exchanging Oneself with Others

So now we come to the fourth step in the meditation, which is the actual thought of exchanging oneself with others. What is meant by exchanging oneself with others? Prior to this, we contemplated deeply the disadvantages of cherishing oneself, realizing that all unwanted experiences and bad things come from egoism. Like a chronic disease which slowly, gradually destroys your health and physical form, the self-cherishing thought has, from beginningless time, been the source of all your suffering and problems. On the other hand, all the good things—good qualities, happiness, advantages and so forth—derive from cherishing others, from altruism. Realizing this, you now begin to train your mind in exchanging the thought which cherishes oneself and disregards others for the thought which cherishes others and disregards yourself.

Until now we have been disregarding others and taking care of ourselves, but from now on, we have to take care of others and disregard ourselves. Exchanging oneself with others doesn't mean that you take others in your place and put yourself in others' place. Instead it means that you exchange the mind which cherishes oneself and ignores others with the mind which cherishes others and ignores oneself. You need to meditate on this again and again, continuously, and in this way train your mind in exchanging yourself with others.

The Meditation on Giving and Taking (Tonglen)

On the basis of the thought of exchanging oneself with others, you practice the meditation on giving and taking. What is giving and taking? With the mind of compassion you take on the suffering of others and with the mind of love you give them happiness. The root text of the Seven-Point Thought Transformation says, "giving and taking should be practised alternately." In the Tibetan term, tonglen, giving comes first—tong means "giving" and len means "taking"—but in actual practice, you first train your mind in taking—taking upon yourself the suffering of others—and leave aside the practice of giving.

Taking

You begin the practice of taking by contemplating the sufferings of the precious mother sentient beings until an unbearable sense of compassion arises within you. Then you visualise that suffering in the aspect of black light, which separates from the sentient beings in the same way that hairs separate from your skin when you shave. You visualise that this suffering in the aspect of black light comes and absorbs into the self-cherishing thought which is at the centre of your heart.

You can do the meditation in an elaborate way, going one by one through all the different realms of the sentient beings, starting from the hells. For example, you can think about the sufferings of sentient beings in the hot hells—sufferings due to the intense heat, fire and so forth—and then take upon yourself this suffering in the form of hot fire, visualising that it absorbs straight into the centre of your heart, into the egoistic, self-cherishing thought.

You continue to meditate in this way, gradually progressing through all the different levels and kinds of sentient beings all the way up the bodhisattvas of the tenth bhumi, taking all their suffering into the centre of the self-cherishing thought in your heart. You take on not only their sufferings but all the obscurations and negativities as well, wishing that they actually ripen upon you, and feel that in this way, all these negativities are completely purified.

For some individuals, it may be difficult immediately to visualise taking the sufferings of others, such as those of the hell beings, pretas and so forth—upon yourself. If that is the case, you need to first train your mind in taking on your own suffering. As mentioned in the root text, "You should begin by taking from yourself." The way to do this is to consider the sufferings that you will experience tomorrow, and take these sufferings upon yourself in the aspect of black light as I explained before. Then take on the sufferings you will experience the day after tomorrow, and so forth—contemplating and taking on all the sufferings of the coming month, the coming year, the rest of your life, the next life, and all the future rebirths—you gradually take on all these sufferings in the aspect of black light, and they absorb into the self-cherishing thought in your heart.

Once you have trained your mind in this meditation and become familiar with taking upon yourself all the sufferings you will experience in the future, from tomorrow through your future lives, then you train in taking on the sufferings of loved ones: your parents, relatives, friends and those who are close to you. Then, when you are familiar with this, train in taking on the sufferings of strangers, those for whom you feel neither attachment nor aversion. Then you switch to your enemies. In this way, meditating with the thought of compassion, you gradually widen your scope to include all sentient beings, taking upon yourself their sufferings in the aspect of black light that ripens in the centre of your heart, the self-cherishing thought.

Giving

Taking is practiced on the basis of intense compassion, and giving is practiced on the basis of love. The way in which you meditate on giving is as explained in the verse, "In order to benefit sentient beings, may my body turn into whatever they wish for." You emanate replicas of your body and visualise that these bodies transform the environment and sentient beings. Let's say you start with the hot hells: you first send out countless bodies which become a cooling rain that completely extinguishes the fires of the hells. Due to the soothing rain, the bodies of the hell-beings transform and they achieve precious human rebirths, with the freedoms and endowments. The bodies you send out also transform into pleasant, enjoyable things such as the objects of the six senses, and in this way you completely fulfil their wishes. Then you again emanate countless bodies which take the aspect of spiritual masters teaching Dharma to those beings who then practice Dharma and gradually achieve enlightenment.

Next, you move on to the sentient beings in the cold hells. This time the bodies you emanate become bright sunlight which completely warms up the freezing environment, and you provide the sentient beings with warm clothes. Again, the beings of the cold hells transform and achieve precious human rebirths, and by emanating countless bodies in the aspect of spiritual guides, you teach them the Dharma and they all reach enlightenment.

You progress through the meditation on each type of sentient being in the same way. For the pretas, the bodies you emanate become food and drink; for the animals, they become wisdom that clears away their ignorance; for the titans, they become armour to protect their bodies; for the devas, they become enjoyments of the five senses; and for human beings, who have such strong desire, they become whatever people need or desire. For the Buddhas and spiritual masters, when you train in giving, you emanate inconceivable clouds of offerings and make prayers for their long lives.

While you are training your mind in the practice of taking and giving, you should also practice the following advice given in the root text of the Seven-Point Thought Transformation: "The instruction to be followed, in brief, is to take these words to heart in all activities." This means that in your meditation and in all your activities, you should use the special words of the tonglen practice as a way to recollect and empower your meditation. For example, you can use the verse from the Guru Puja which says:

O venerable, compassionate Guru, bless me.

May all the sufferings, negative actions and obscurations

Of all beings, who were once my mothers,

Ripen on me now, without exception.

May I give all my happiness and virtue to others

And may all beings have happiness.

So while you are training, in your actual meditation and throughout all your daily activities, you should continuously recite this verse. These words from the Guru Puja are so powerful, so full of blessings, that it is indeed very important to recite them all the time. There is even a practice of accumulating one hundred thousand repetitions of this verse while meditating, and this would be an excellent practice to do.

In the prayer, you first entreat the lama by saying, "O venerable, compassionate Guru," and then you say, "bless me—may all the sufferings and negativities of all the precious mother sentient beings ripen on me right now, without exception. And bless me to give all my roots of virtue and goodness to others, so that these may ripen upon them." The verse concludes with the prayer: "may all sentient beings have happiness." This is really an exceptional, powerful prayer.

It has become a tradition that when the Guru Puja is recited, this verse is repeated three times. This tradition was initiated by Lama Pabongka Dorje Chang. Before his time, the Guru Puja would be recited straight from the beginning to the end, but because he placed so much importance on this verse, he began the practice of reciting it three times. So the fact that this tradition has continued up to now is due to the kindness of Lama Dorje Chang.

Practicing Giving and Taking with the Breath

The next verse in the root text says, "These two, taking and giving, should be made to ride on the breath." This means that after you have become familiar and proficient with the meditation as explained, then you should combine the meditation with your breathing. The way to do this is as follows: while you are breathing out, think that you breathe out all your goodness, and this transforms into whatever is needed for the benefit of sentient beings. You breathe whatever goodness there is within you—your body, virtues, richness, and so forth—and this transforms into whatever benefits all sentient beings.

Then, when you breathe in, think that along with the flow of your breath come all the sufferings of all sentient beings in the form of black light. These sufferings in the aspect of black light enter you and go straight to the source of all the negativities and sufferings you have experienced since beginningless time—your egoistic, self-cherishing thought—and they ripen right there, in your heart. Your see, the mind and the breath are inseparable. The mind rides on the breath, so this visualization that combines giving and taking with the breathing becomes a powerful cause for generating bodhicitta. It's also similar to the vajra recitation which is found in the practice of highest yoga tantra.

It is very beneficial to do this practice as you are going to sleep. Before you go to sleep, generate the thought of love and do the visualization of giving while breathing out; then with the thought of compassion do the visualization of taking while breathing in. If you go to sleep doing this practice, then the whole time you are asleep, especially if you like to sleep a lot—until eight or nine in the morning!

As for myself, the more i progress in years, the more I need to sleep, and also my sleep gets deeper. But when I was young and studying at Sera Monastery, I had the habit of staying up all night. The night is very long and you can do so many things—you can do prayers, read texts, whatever you want to do. In the early morning, at dawn, I would feel so happy. My mind would feel very fresh and I would rejoice from the depths of my heart, thinking, "How lucky I am! I was up all night and was able to do these things while the majority of the people around me were asleep." I would consider myself so fortunate to be able to stay up all night and practice. This is something Venerable Lama Thubten Zopa Rinpoche does. But now, as I grow older, I need more sleep, so I am unable to stay awake all night even if I want to.

I really want to stress the importance of transforming sleep into virtuous practice because if you calculate the way you spend your life, almost half of it is spent sleeping. Therefore it becomes very crucial that the time you spend sleeping becomes virtuous practice, doesn't it?

In his Songs of Experience, Milarepa said, "At night, sometimes I sleep, and when I sleep I practice merging sleep with the clear light, because I have received instructions on the clear light of sleep. Other people do not have these instructions—how lucky I am!" There are very few people who are actually able to merge sleep with the clear light practice, so for the majority of us who are beginners, it is extremely practical and useful to go to sleep while meditating on giving and taking. In this way, the entire time you spend sleeping becomes the actual practice of tong-len, and thus becomes virtuous.

Practicing in Daily Life

Actually it is extremely important that all the actions we do—sitting, walking, going, coming and so forth—become Dharma. If you divide twenty-four hours into two parts, almost the whole of one part is spent sleeping, and if your sleep is not transformed into virtuous practice, then it becomes empty and even non-virtuous. That means that half the day has disappeared in non-virtue. Then you wake up and, even if you generate a very strong motivation to practice virtue during the day, it is extremely difficult to maintain it. When you sit down to do your prayers, sometimes your mind is so distracted and goes in so many different directions that you're not even sure whether or not you have done all the prayers up to the point you've reached in your recitation. So you have to go back and recite those prayers all over again to make sure that you have at least completed all your commitments.

If it is difficult to generate a pure, virtuous state of mind when reciting prayers, how much harder it is to do so during the day when we are engaged in social activities, especially when most of our time is spent gossiping. Whenever we have the chance to talk, right away we start talking and then we spend so much time gossiping, which is a non-virtuous action, isn't it? Therefore it is extremely crucial that we transform as many of our actions during the day and night as we possibly can into virtue, into Dharma practice.

If we transform our actions into Dharma then we will make our life meaningful. The most important thing is to begin in the morning, as soon as we open our eyes, by generating a very strong motivation. We should think, "I'm still alive this morning, so I'm very fortunate. Due to the kindness of the Three Jewels, I didn't die last night. Therefore I must make this coming day as meaningful as possible by practicing Dharma."

After generating a strong motivation in the morning, you should carry it through the day, reminding yourself of it again and again, in all your activities. Normally, the first thing you do after getting up is to jump into the shower, so while taking a shower you can practice the yoga of washing together with the ablution mantras, or do a purification practice. Following that, if you don't have to go to work, you can sit down and begin your daily meditation commitments. Otherwise, if you have to go to work, you can use your time at work to create virtue. If your job mainly involves physical activity, then you can turn your speech and mind to virtue—the mind especially can be made virtuous by recollecting again and again the motivation you generated in the morning.

Then you come to lunchtime. We normally eat at least three times a day, and when eating we can practise the yoga of taking food, which is part of deity yoga. There is a quotation from the great yogi Drogchen Lingrepa which says, "All the holy places are in your body—in your chakras. You don't have to go away. If you want to make pilgrimage, visit there. If you want to do the practice of purification and collecting merit, do it there, in your chakras, in your holy places." According to the practice of deity yoga, the assembly of deities resides in the subtle body of the psychic channels and chakras. Therefore, when you practice the yoga of eating, you visualise the deity's holy body or the body mandala and use the food to make tsog offering. Lama Dorje Chang used to quote this verse—it's very nice.

As you continue with your usual daily activities, remind yourself again and again of the motivation you generated in the morning. Then at night, before going to sleep, think over what you did during the day and check whether or not you have acted in accordance with your motivation. If you realise that you did any negative actions, confess and purify them, but if you realise that your actions were completely compatible with your motivation, then rejoice in all the virtues you created throughout the day.

The Kadampa lamas of the past used to keep count of their virtuous and non-virtuous actions. They kept two piles of stones, one black and one white. Whenever they noticed a delusion or a disturbing thought in their mind, they would add a black stone, and whenever a virtuous thought rose, they would add a white stone. At the end of the day they would count the black and white stones. They would confess and purify the delusions and negativities they had created, and generate the strong intention to keep their mind free from those negativities the following day. They would rejoice in whatever virtues they created and resolve to create even more the next day. Then they would go to sleep doing the practice of merging sleep with the clear light. This may be very difficult for us to practice, so it is important for us to go to sleep merging our sleep with the practice of tonglen.

The Eleven-Point Meditation of Developing Bodhicitta

As I mentioned earlier, when you actually undertake the practice of training the mind in bodhicitta, there is a way of combining the two sets of instructions—the seven-point technique of cause and effect and exchanging oneself with others—into eleven steps. This is according to the tradition of Lama Tsongkhapa. By meditating on either of the two techniques alone, you will definitely generate bodhicitta. However, this uncommon way of merging the two and meditating on the eleven points enables you to generate bodhicitta more quickly and with less hardship.

How do we merge the two techniques into eleven steps?

(1) First of all you meditate on equanimity, visualising a friend, enemy and stranger.

(2) The second point is to recognize all sentient beings as your mother, by using the reasoning of the beginningless nature of the mind and by reflecting on different quotations.

(3) Third is recognizing the kindness of sentient beings when they were your mother, just as your mother of this life is kind to you in the beginning, middle and end.

(4) Next is the uncommon point of recollecting the special kindness of sentient beings when they were not your mother.

Then you meditate on:

(5) the equality of self and others,

(6) the disadvantages of the self-cherishing thought; and

(7) the advantages of cherishing others.

(8) Following that, with a mind filled with compassion, you do the meditation of taking upon yourself all the sufferings of sentient beings, and later incorporate this meditation with the breath.

(9) Then with a mind of incredible love, you give all sentient beings all your goodness and roots of virtue, sending these out with the breath as you exhale.

10) At this point you generate the extraordinary intention by thinking, "I have been meditating on taking upon myself the suffering of all sentient beings and giving them all my goodness and roots of virtue, but this has been only on the level of visualization—it hasn't actually happened, but I am definitely going to make it happen in reality. I myself will definitely take on the suffering of all sentient beings and give them all the roots of virtue and happiness that they wish for." Thinking this way you generate a very special sense of responsibility.

11) In order to fulfill this responsibility, you generate bodhicitta: "I am going to become a Buddha in order to help all sentient beings."

At this point you take the result of bodhicitta into the path by visualizing that you transform into the aspect of Buddha Shakyamuni, emanating countless rays of light which purify all sentient beings and lead them to the state of the Buddha. Visualize that they all transform into Buddhas, and stabilise your meditation on this. Conclude the meditation session by rejoicing that you have actually been able to bring all sentient beings to the state of enlightenment.

Transforming Adverse Circumstances into the Path to Enlightenment

The next section of the root text, the Seven-Point Thought Transformation, deals with transforming adverse circumstances into the path to enlightenment. This practice is absolutely crucial, especially for the present degenerate time in which we live. In this degenerate age there are so many obstacles, especially for Dharma practitioners. This practice enables the practitioner to take all the obstacles, all the adverse circumstances, and transform them into conducive circumstances and even into the actual path to enlightenment. In fact, it enables the practitioner to not have any obstacles at all.

This section is divided into two points: transforming adverse circumstances by way of thought and by way of action. The first, transforming adverse circumstances into the path to enlightenment by way of thought is further divided into two: by using reasoning and by using the view.

With regard to the first, using reasoning, the root text says, "When the environment and its inhabitants overflow with unwholesomeness, transform adverse circumstances into the path to enlightenment." And the commentary quotes from the Guru Puja:

Should even the environment and the beings therein be filled

With the fruits of their karmic debts

And unwished-for sufferings pour down like rain,

We seek your blessings to take these miserable conditions as a path

By seeing them as causes to exhaust the results of our negative karma.

For example, when we get sick we tend to think that it is because of the food we ate, or because of spirits or obstacles, or because someone had cast a spell on us. These are the reasons that come to our mind. This is a clear indication that we are not able to recognise the real root of the sickness and to understand why we are experiencing that particular problem. We need to go back and look at [the section in the lamrim on] the training for the individual of the small scope, which explains the teachings on evolutionary actions and results. Here it clearly explains that results are experienced due to karma, due to actions which we created in the past. It does not explain that a result such as sickness comes from eating a particular kind of food, or because someone has cast a spell on us, or because we are possessed by spirits. It explains that the results we experience are due to evolutionary actions created in the past. Therefore it really is indispensable to know how to transform adverse circumstances such as sickness into circumstances conducive to the attainment of enlightenment.

If you pay very careful attention to the advice of the old Kadampa lamas, it is so beneficial for the mind. They said, "Sickness and pain are the broom which sweeps away negativities." If you think about this advice, it is really powerful. It means that what bring the results of sickness, pain and suffering are the negative evolutionary actions which you accumulated in the past. By experiencing the result, that particular negative karma is cleared away, swept away by the broom of suffering. The advice of the old Kadampa lamas is so powerful.

This advice must be practised continuously. We should think in this way whenever we experience physical or mental suffering. In particular, we should think that up to now we have meditated so much on tonglen, giving and taking, and have made many prayers that all the suffering of all sentient beings without exception may ripen upon us. Now our prayers are bringing some result—we are getting what we wished for—therefore we should rejoice. We should even wish for more suffering to come—the more suffering, the better. Why? Because the more suffering we experience, the more accumulated negativities are cleansed. We can actually get to the point where we wish for more suffering to ripen upon ourselves because we understand that that is what cleanses the negativities.

There is nothing more beneficial that the practice of lamrim and thought transformation at times of experiencing physical and mental suffering. This is something I have experienced myself. For instance, there were times when I experienced incredible hardships, incredible sufferings of body and mind. At those times, I was able to think that all these sufferings and hardships were the result of past evolutionary actions and that by experiencing them, the negativities will be completely purified. Then in my mind came the thought that the more suffering that comes, the better it is, because in that way more negativities will be purified. It is due to the kindness of my gurus—having received the teachings of thought transformation from Lama Pabongka Dorje Chang and also many times from the late Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche—that when I went through incredible pain, suffering and hardships of body and mind, I experienced the thought of not wishing the suffering to end. When difficulties come, I don't need to be afraid. In Tibetan the word for "existence" is sipa, which also means "possible". In existence, anything is possible, anything can happen. However, on the basis of practicing the teachings of lamrim and thought transformation, you can reach a point where no matter what hardships or difficulties occur, your mind is unshakeable. Your mind cannot be shaken by suffering, hardship or adverse circumstances.

The sayings of the Kadampa lamas are so true. For example, they say, "Adverse circumstances are an incentive for practice," and "Sprits and possession are manifestations of buddhas, and suffering is the manifestation of emptiness." Another saying goes, "I don't like happiness, but I like suffering." Why did they say this? When we experience happiness, we consume the merits accumulated in the past; when we experience suffering, we purify negativities accumulated in the past. Therefore it is much better to experience suffering that happiness. As for ourselves, we like happiness and don't like suffering, but the advice of the Kadampa lamas is completely opposite: "I don't like happiness because in that way I consume merits, but I like suffering because in that way I purify negativities."

Another advice of the Kadampa lamas is, "I don't like a high position, I like a lower position." For us it is completely the opposite: we always like to be on top and don't like to be down below. However, the lower position is the position of the Victorious Ones, which allows one to proceed to become a Buddha. The Kadampa lamas also said, "I don't like praise, but I like criticism." Why is this so? Although we feel uneasy when we receive it, criticism is actually very beneficial because it allows us to see our faults and to change on the basis of that. If we receive nothing but praise, the only thing that increases is our pride. Praise is therefore not beneficial, and it is even damaging because it increases our delusions. Criticism on the other hand allows us to identify our faults and work on them.

Transforming Adverse Circumstances by Way of the View

So now we come to the thought transformation practice of transforming adverse circumstances into the path by way of the view. This is done by reflecting again and again on the fact that if you search for the actual entity of what an adverse circumstance appears to be, if you search in depth, you cannot find a single atom which exists on its own, by its own nature. Instead, what you find is just what is merely labeled. It is completely unfindable in nature; ultimately it is not there. You have to bring this thought into your mind again and again.

However, if you are not proficient in analyzing the nature of phenomena with the view, then you should think in this way, "Whatever happens to me in this very short life, whether it is happiness or suffering, at the end of this life all those experiences will be just memories. They are like dreams, completely insubstantial, so there is absolutely no reason to grasp at them with attachment or aversion. There is not even a single atom of them that I can grasp with attachment or aversion."2

The Importance of Bodhicitta

In conclusion, the most important thing is to apply one's energy as much as possible towards the development of bodhicitta in this life. The significance of bodhicitta was shown by the way Lama Atisha greeted people. When we meet people we usually say, "How are you?" or Ni how ma? Lama Atisha, however, would greet people by asking, "Do you have a good heart?" or "Has the good heart arisen within you yet?" This showed the importance he gave to the practice of bodhicitta.

As I mentioned earlier, the great master Shantideva said that just as we churn milk to extract its essence, butter, we should extract the essence of the 84,000 heaps of teachings given by Buddha Shakyamuni—this essence is bodhicitta. Therefore, as bodhicitta is the essence of the entirety of Buddha Shakyamuni's teachings, we must definitely make an effort to develop bodhicitta in our mind in this very life.

Notes

1. See Keith Dowman & Sonam Paljor, The Divine Madman—The Sublime Life and Songs of Drukpa Kunley. London, 1980. [Return to text]

2. Earlier Ribur Rinpoche mentioned that one can also transform adverse circumstances into the path to enlightenment by way of action, but he did not elaborate on the point. As found in Advice from a Spiritual Friend (Geshe Rabten and Geshe Ngawang Dargyey; wisdom Publications, London, 1986, pgs. 68-69), this includes the practice of accumulating merit, purifying negative karma, and making offerings to harmful spirits and dharma protectors. [Return to text]

Lama Tsongkhapa said, in Songs of Experience, that to have attained a human body is a very rare experience and it should be used to its maximum potential for the Dharma. This human body has great potential if used positively but also great power if used negatively. We can illustrate the great potential of human rebirth by putting all the animals of this universe on one side and a single human on the other; even the combined number of the other sentient beings cannot equal the potential and ability that one human has to do positive actions.

Lama Tsongkhapa said, in Songs of Experience, that to have attained a human body is a very rare experience and it should be used to its maximum potential for the Dharma. This human body has great potential if used positively but also great power if used negatively. We can illustrate the great potential of human rebirth by putting all the animals of this universe on one side and a single human on the other; even the combined number of the other sentient beings cannot equal the potential and ability that one human has to do positive actions.