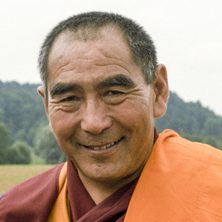

| A teaching on The Three Principal Aspects of the Path by Ven. Denma Lochö Rinpoche at Jamyang Buddhist Centre, London, in early October 2001.The Three Principal Aspects of the Path is a text by Lama Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) which covers the entire Buddhist path to enlightenment. |

CHAPTERS

Part 1: Renunciation

Part 2: Renunciation

Part 3: Bodhicitta

Part 4: Correct View of Emptiness

Part 1: Renunciation

Motivation

So when we begin the teaching with the prayer of going for refuge and then the aspiration to the highest enlightenment, that is to say, buddhahood for the sake of all sentient beings, then we recite the four-line prayer as we have just done. So within that, as you know, we should recite, 'through the merit I receive by engaging in listening to this teaching, may I achieve buddhahood for the sake of all sentient beings'. The lama who is giving the discourse recites 'through the merit I achieve through explaining the Dharma'. So as we, the disciples, are not explaining the Dharma, then we needn't recite this, so we should recite 'through the merit I receive through listening to this teaching, may I achieve buddhahood for the sake of all sentient beings'.

So one of the most important things before receiving a Dharma teaching is one's motivation for receiving the teaching. So our motivation should be one that is in accordance with the Dharma, that is to say, in accordance with the Three Jewels. So what should our motivation be? Most of us already know, but it's good to go over that. One should listen to the teaching with the thought 'I must achieve the highest unsurpassable enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings in order to lead them out of the state of dissatisfaction into one of everlasting satisfaction'. So with this motivation one should then listen to the teachings, not rather with the motivation to gain fame or renown or some kind of strange blessings; rather one should adjust one's motivation or attitude to one of achieving the highest enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings.

The Benefits of Listening to the Dharma

So with regard to this attitude or motivation for receiving the teaching - initially if we understand the benefits of listening to the teaching, of receiving the Dharma discourses, then we will willingly engage in the practice of hearing the teaching, or delight in hearing the teaching. So then we should understand this through an example: If we are engaging in some kind of worldly work, for example a business, if we understand the benefits of engaging in a certain business deal, then we will put a lot of effort into that business deal, we won't have a two-pointed mind, that is to say, we won't have doubt with regard to that deal because we will have firstly seen the benefits, understood the actual deal itself and then engaged in that action. So in the same way when engaging in the practice of Buddhism, then initially one should understand the benefits of engaging in the Dharma practice.

So this is understood through understanding a quotation from a book which talks about the benefits of hearing the Dharma. So within this text then it first instructs that we should delight in the practice of hearing the Dharma because through this all qualities arise. So what is meant by this is that through engaging in the three higher trainings, we achieve the state of liberation; whether we are engaging in a lesser vehicle practice or in a greater vehicle practice, we achieve the result which is the state of liberation. Of those three higher trainings, the most important is the one of wisdom. So with regard to this wisdom which is crucial at the base and path and resultant level of the path, then how does this come about, how do we generate this wisdom within our mind, or within our being? We generate this through initially hearing a teaching about wisdom and then engaging in that particular practice. So initially then, the benefits that come about through engaging in the three higher trainings - the state of liberation and so forth - all come about through initially hearing the Dharma teaching.

Then the second line from that text goes on to say that through listening, negativity, or non-virtue, is reversed. So what this means is that through hearing the teaching, we understand what is virtuous to take up and what is non-virtuous and thus what are the objects to be abandoned. So this is principally talking about the higher training of morality. So here then if we talk about restraint - what is meant by 'restraint' here is the subduing of negative actions or negative states of mind. So this again is something that is learned through hearing the teaching. So through hearing the teaching we understand what is meant by a negative action and how to refrain from that particular action - we understand what is the base, what is the motivating factor, what is the intention with regard to the particular action or the particular karmic deed which we are going to perform and then what is meant by the rejoicing in that action afterwards. So then if we don't understand this fourfold mode of action, then we can easily engage in negative actions, and then the ripening result of those, or the negative result of those, which will inevitably come will just be something that causes us displeasure later on.

For example, if we have not heard the Dharma teaching about the necessity of abandoning the negative action of stealing, we might engage in the practice of stealing, through borrowing something and not returning it, or we might engage in the practice of killing through being pestered by an insect, and through this we will inevitably receive the result of such actions. If we don't want to have such unpleasant karmic results, we need to know what actions to abandon, and the only way we are going to understand what actions are to be abandoned is through hearing the Dharma teachings. So again here then, the praise of listening to the Dharma teaching is that one will know exactly what negative actions to reverse and this is only understood through initially engaging in the practice of hearing a teaching upon that.

So then the third line talks about the higher training of concentration. So if we talk about the mind of calm abiding, or shamatha, then this mind is one which spontaneously and effortlessly remains single-pointedly upon its object of observation. So let's talk about the achieving of that state of mind - what does one need to initially engage in? One needs to initially understand what is meant by the object of observation, the object upon which we are going to generate this single-pointed mind, this single-pointed concentration. Then we need to understand what are the beneficial mental factors which we need to take up, for example faith in the practice, introspection and so forth. Then we also need to know the objects of abandonment which are abandoned by these positive attitudes, for example mental sinking, laxity and so forth. So when we understand what is to be taken up and what is to be abandoned on this path of achieving this single-pointed mind of concentration, we will be able to engage in this particular practice of achieving a mind of calm-abiding. So again, we only know what objects are to be taken up and what objects are to be abandoned (in this case, mind-states) through engaging in the practice of hearing the teaching about this particular mind-state, or the mind of calm abiding.

Then the last line says that in essence one achieves the state of liberation through hearing the teaching. So here when we talk about having engaged in the practice of the three higher trainings, the natural result of that is to achieve the state of liberation. If we look for the root cause of achieving the state of liberation, we will find that it is hearing the teaching. So initially when one engages in the practice of hearing the teaching, then generating the various wisdoms which arise form hearing, and then contemplating the teaching, and then meditating single-pointedly on the teaching, then through having done that one generates the yogic direct perception of suchness, and then through single-pointed placement on that, one goes through the various stages and paths and achieves then the state of omniscience. So all good qualities arise through initially engaging in the practice of hearing the teaching, thus hearing the teaching is incredibly important.

The Root Text

So after having gone through the benefits of listening to the Dharma, we should engage in the practice of listening to the Dharma teaching. So the Dharma teaching which we are going to receive today is known as The Three Principals of the Path. So when we talk hear about 'path', what is meant by 'path'? In general we can talk about various kinds of path, for example, a road or a rail-track, something which gets us from A to B. However in this instance, we are not talking about a worldly path, we are rather talking about a spiritual path, and what is meant here by a spiritual path is one which gets us from a spiritual A to B, travelling through the various stages, based upon the oral instructions of the past masters, the present masters, and then taking those instructions to heart, putting them into practice, and through that moving through various stages of spiritual evolution. Here 'principal' then refers to the main points of the path, like for example snatching the essence from what is known as the Lam-rim (or the graduated stages of the path to enlightenment) teachings. So when we talk of these 'three principals of the path', we talk about a person of smaller, middling and greater capacities and then the practices which are in common with a person of smaller, middling and then the pinnacle practice which is unique to a person of greater capacity. So within that division of three, what we find are various divisions and sub-divisions, but the essence is all kind of snatched together and put in these three principals of the path, which we are going to go through.

So this particular text was composed by Lama Tsongkhapa and it was something which he received while in communication, if you like, with Manjushri, and it is the heart-essence of his practice and also of the Lam-rim genre of texts. So this was requested by a disciple of his who lived in a place called Gameron which is on the Chinese-Tibetan border. This monk requested him to give him some inspiring word for his practice, and then Lama Tsongkhapa wrote this to him based on the teachings he had received in the pure vision, thus we have the written form of The Three Principals of the Path.

The Three Principals

So if you ask – ‘what are these three principals of the path?’ Initially then it’s renunciation. So 'renunciation' here refers to a turning away from the faults of the cycle of existence and yearning or directing one’s spiritual career towards liberation from such a state of existence. Then the second is the mind of bodhicitta. This refers to a mind which for the benefit of all sentient beings, through seeing sentient beings’ suffering, strives to achieve the highest state of enlightenment in order to be of maximum or optimum benefit. So through seeing the faults in one’s state of mind, through abandoning those, gathering all the qualities, achieving the mind of omniscience of the Buddha - this desire to achieve such a state - the mind of bodhicitta - is the second of the three. Then the third of the three is what is known as the 'correct view', also known as 'wisdom'. 'Wisdom' here then refers to the mode of abiding of phenomena, that is to say the middle way view - 'middle way' here being a middle way between the two extremes of annihilation and permanence. So this correct view of reality then is the third of the three principal aspects of the path.

Prostration

So then initially we have the prostration and then the promise to compose the text. So initially then we have the first line of the text:

I bow down to the venerable lamas.

So then we should understand what is meant by this prostration - who is the object towards which the author is making this prostration? It is the field of merit, that is to say, the field upon which the prostrator, or the one making the supplication, receives the maximum amount of merit, that is to say, one's spiritual mentor, or one's lama. So here then the prostration is made to the venerable lamas. So here then we should understand what is meant by 'venerable lamas' by looking at the Tibetan word. If we look at the etymology of [Tib] - the first part [Tib] refers to the lama having heard a lot of teaching, that is to say, the lama is very knowledgeable about the Buddhist practice. Then the second part of that word [Tib] refers to not only having heard the teaching but then has accomplished, or has gained realisation of, that teaching through putting it into practice in a faultless fashion. So this then refers to the level of realisation of the lama. So here then [Tib] together refer to the lama's knowledge and then the realisation of that knowledge. Then the third word 'lama' - if we look at the meaning of this word, what we find is that it refers to the highest, or that of which there is none higher. So then this is the name given to one's spiritual master with whom there is none higher with regard to the knowledge of the teaching and the realisation of that teaching. So thus we have [Tib]. In Tibetan, there is the plural [Tib] - so [Tib] here refers to the various lamas of the various lineages, that is to say, of the profound lineage, of the vast lineage, there are many what we call 'lineage lamas'. So through saying 'I bow down to the venerable lamas' - using the plural, the author is showing his willingness to bow down before all the lamas of the lineage and in particular then his principal teachers.

The Promise to Compose the Text

So then we have now reached the first stanza which is the promise of composition, so I will read from the root text:

I will explain as well as I am able

the essence of all the teachings of the Conqueror,

the path praised by the Conqueror's offspring,

the entrance for the fortunate ones who desire liberation.

So here when we talk about 'the teachings of the Conqueror', the 'Conqueror' here then refers to the Fully Enlightened One, the Buddha, and then 'the essence of the teachings' here - whether it be the various sutras or the various teachings of the Secret Mantra and the fourfold division therein, the essential part of all of this is what is going to be explained. So here then we have to understand what is meant by the teaching of the Buddha. It wasn't that the Buddha just gave a teaching and then everybody had to follow that teaching. Rather, as is mentioned by Nagarjuna in the 'Precious Garland', the Buddha teaches as a grammarian instructs his pupils. That is to say, a grammarian doesn't just teach advanced grammar to... [end of side - tape breaks here]

Renunciation

…initially then one would learn the alphabet, so you would learn the basic Tibetan grammar like [Tib], or in English 'A, B, C', then in dependence upon that you would learn how to form words and then sentences and then advance up into advanced grammar and so forth. So the Buddha taught his disciples in much the same way, that is to say, in a method which would lead them along a path. So 'path' here then is referring initially to renunciation. So there are two kinds of renunciation which are mentioned - one is to turn one's attention away from this life in and of itself and towards one's future lives; then to turn one's mind even away from future lives and put one's mind in a state where one wishes to achieve liberation from the cycle of existence. So thus then there is turning away from this life and then turning away from future lives, thus two kinds of turning away, and these are taught in stages to the aspiring disciples. In essence, we can say that the Buddhist teachings are taught as a method to subdue one's unruly mind, to subdue the destructive emotions which we find therein, and then to develop the spiritual qualities on top of that. So this is what is meant by 'the essence of all the teachings of the Conqueror', and here 'Conqueror' refers to having conquered all others, thus the Fully Enlightened One.

Bodhicitta

So then the second line of The Three Principal Teachings of the Path (which is the first in Tibetan) talks about the practice of renunciation. The third in English (and the second in Tibetan) - 'the path praised by the Conqueror's offspring'. So here then let us have a look at the word 'Conqueror's offspring'. Here then if we read from the Tibetan it says the holy Conqueror's offspring, or the exalted Conqueror's offspring. So this word 'exalted' means that a person in whose mental continuum, or mind, the wish to achieve full awakening for the benefit of all sentient beings has arisen, becomes a superior individual, thus kind of a holy individual. At that moment of generating the mind aspiring to the highest enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings, a lot of negative karma is destroyed, and that person then becomes what is known as one of the 'Conqueror's offspring', or the son or daughter of the Victorious One. This is mentioned quite clearly in Shantideva's book called The Bodhicaryavatara where it says that just through having given rise to this, no matter what caste one is born to, one becomes renowned as the son or the daughter of the Victorious One. So no matter what caste or what colour one might be, one is equal in the sense that one will be equally regarded, through having given rise to this mind, as the offspring of the Victorious One. This mind then is one is which is extremely important and its importance cannot be overestimated because through this mind one achieves the state of buddhahood, and if one doesn't have this mind, if one hasn’t given rise to this thought, then no matter what practice one engages in, one will not come any closer to the state of omniscience.

Correct View

Then the next line reads 'the entrance for the fortunate ones who desire liberation'. So 'fortunate ones' here then refers to those who are engaging in the Buddhist practice - fortunate in the sense that we have become into contact with the Buddha's teaching and are able to put them into practice, and in particular, fortunate in the sense that we have come into contact with the teaching of the greater vehicle, or the Mahayana teaching. So this sentence is describing the third of the three principals of the path which is correct view, correct view of reality. Because as the line says, 'the entrance for the fortunate ones who desire liberation'.

So here then 'desire liberation' - what is meant by 'liberation' and how does this sentence teach us about the correct view of reality? Here we have to understand what is meant by 'liberation'. So liberation then refers to a kind of release or an escape. So if there is a release, something has to loosen so we can escape from it, or if there is an escape there has to be something from which we are going to escape. So here then what we are escaping from or loosening and then getting away from is the destructive emotions, and then action, or karma. So these are the two fetters which bind us to the wheel, or cycle, of existence. So it is only through removing ourselves from the destructive emotions and action that one is able to achieve liberation.

So then if we think about what the cause of the destructive emotions and karma is, we can say that the root of the causes of cyclic existence (that is to say, of the destructive emotions and then the action which is brought about through them) is grasping at a truly existent or self-existent self or 'I'. So then if one wants to reverse this root, one needs to understand how this root is baseless, that is to say, we need to understand how phenomena actually exist and how, perceiving them in a wrong way, we develop these destructive emotions and then through having brought about these destructive emotions, we engage in action, the result of which is the wheel of existence, that is to say, the state of dissatisfaction. If we look at action and destructive emotions in and of themselves, then we find that the strongest of the two is the destructive emotions. If we look at the destructive emotions, then we find in the various college text books that there are two kinds, that is to say, the root and then the secondary destructive emotions, but whether it be root or secondary, these destructive emotions are emotions which cause us to have an unpeaceful or disturbed mind. So those states of mind are those which we are seeking to abandon through uprooting the root of those destructive emotions, that is to say, wrong view. So that which is going to uproot the wrong view is the correct view which is taught here in the third line - 'the entrance for the fortunate ones who desire liberation'. 'Entrance' here then referring to the path which one has to engage in if one wants to achieve liberation, that is, the removal of the destructive emotions and the actions which come about through that.

Then the last line in the Tibetan which is the first in English is 'I will explain as well as I am able'. So through this we see that Je Rinpoche was a very humble individual. He in fact was an incredibly learned person, so he could easily have written 'I am going to explain the subject matter better than others or in a different way to others' but rather than that he wrote 'I will explain as much as I can, as well as I am able', then he went on to give the rest of the verse. So this clearly shows that Lama Tsongkhapa himself was a very humble individual who always took a low status.

The Cycle of Existence

So that concludes the promise to compose the text. The next stanza is a request to listen well to the teaching which is to follow. So in English it reads:

'Listen with clear minds you fortunate ones

who direct your minds to the path pleasing to the Buddha,

who strive to make good use of leisure and opportunity

and are not attached to the joys of samsara.'

'Not attached to the joys of samsara' here refers to having turned away from the pleasures in which one may indulge in the wheel of existence, that is to say, samsara. So having gained precious human existence which is adorned with leisure and opportunity, then engaging with effort in the practice of the path, then to make use of this human opportunity which we now have in our hands by directing our minds to the path which is pleasing to the Buddha. Here 'pleasing to the Buddha' means the path of the greater vehicle, that is to say, having engaged with effort in the practice of generating the mind aspiring to highest enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings, and then engaging single-pointedly in that practice, thus the path which is pleasing to the Buddha. Then for the disciples listening to the discourse then - 'listen with clear minds you fortunate ones' - 'fortunate' in the sense of having come into contact with this particular teaching and then engaging in the practice thereafter.

So then the next stanza of the text reads:

Those with bodies are bound by the craving for existence;

without pure renunciation there is no way

to still attraction to the pleasures of samsara.

Thus from the outset, seek renunciation.'

So this stanza then teaches us that initially one should strive to generate a mind which is turned away from the world, that is to say, a mind which is free from seeking the pleasures of the cycle of existence, so one's attraction to those fetters have been reversed and thus one is striving in the opposite direction, that is to say, striving to achieve release from the cycle of existence. If one initially doesn't seek release from the cycle of existence, one isn't going to be able to get out of the cycle of existence, one isn't going to find any release from the cycle of existence within that. So initially one should seek renunciation from that cycle of existence. So as the text tells us, 'without pure renunciation, there is no way to still attraction to the pleasures of samsara', thus one will not be able to turn away from the pleasures of samsara, therefore one will still be trapped within that. So the first line reads 'those with bodies are bound by the craving for existence' - 'those whose bodies' then refers in particular to human beings who are bound by this craving for existence. So this craving is one which has to be reversed before one can really start out on the path of liberation.

Contemplation on the Preciousness of Human Existence

So then the next stanza reads:

Leisure and opportunity are difficult to find;

there us no time to waste.

Reverse attraction to this life, reverse attraction to future lives.

Think repeatedly of the infallible effects of karma

and the misery of this world.

So here then we are taught about renunciation, renunciation away from initially this life and then subsequently from future lives, so two kinds of renunciation are thus taught. So with regard to the first practice of turning one's mind from this life, one can bring about this change in one's attitude through reflecting on the preciousness of human existence, precious human rebirth, and then through the impermanence of human life. So through these kind of contemplations and the contemplation of action (cause and effect), one can turn one's mind away from the pleasures of this life and bring to mind the future lives which are yet to come. So the basis on which we can do this kind of contemplation is our human existence, that is to say our precious human rebirth which we now possess, a life of leisure and opportunity, which the text then tells us are difficult to find.

So if we want to quote, for example, from Lama Tsongkhapa's works, then we read that this human existence is more precious than a wish-fulfilling gem. So how is it more precious than that gem? In the worldly sense, if we have a wish-fulfilling gem, if we polish it, and put it atop a pole then whatever prayers we make to this wish-fulfilling gem are instantly fulfilled, through which we can have all the riches and enjoyments in one lifetime. But with regard to future lifetimes, there is nothing we can take with us. It is only in dependence upon this kind of human existence which we have now that we can put ourselves in a position where we will achieve the status of human being or god in the future, or if we so wish, the various kinds of liberation, that is to say, the greater and the lesser vehicle liberations from the cycle of existence. This can all be brought about only through dependence upon the support of precious human existence which is more precious than the wish-fulfilling gem in that we can fulfil our future aims through and in dependence upon this precious human existence.

Then it says that this human existence is something which is difficult to find. So here then we should understand why it is difficult of find, and this we can understand through two key points, that is to say, difficult to find because its cause is difficult, and through an example. So initially then through an example: In the sutras we read that the Buddha was once asked 'What is the difference between beings in the higher realms and those in the lower realms?' So to answer this the Buddha put his finger in the earth and said 'the amount of dust which I have on my fingertip symbolises those beings in the pleasurable states, or the states of bliss, whereas all the other grains of sand and dust which are on the face of the earth resemble those who are in the unfortunate states, or the states of suffering and misery'. So through that example we can see that having an existence which is within this fingertip of dust, that is to say, in the realms of bliss, or the higher realms, is something extremely difficult to achieve, whereas if we look all around us it's impossible even to count the amount of dust one might come into contact with in the street, something which is completely uncountable.

Then with regard to the cause, the cause is principally to guard ethical behaviour. So this is the root cause and this needs to be supplemented with the practice of the six perfections and complemented by stainless prayers. So we might think that if we don't keep virtuous or ethical behaviour but rather engage in the practice of the six perfections we may achieve some higher existence as a human, but as Nagarjuna mentions in his book, what we find is that wealth comes about through the practice of the perfection of giving, while the states of bliss (that is to say, the higher realms of existence humans, gods and so forth) come about through engaging in the practice of ethical conduct. This is commented upon by Chandrakirti in his book Entrance to the Middle Way when he says that through engaging in the practice of generosity, it doesn't necessarily follow that one will be reborn in the states of bliss (that is to say, in the higher states of existence), because even if one engages in the practice of giving, if one doesn’t protect one's ethical behaviour one may be reborn as a spirit which is quite wealthy or, for example, a snake spirit, a naga spirit, which is well-renowned for having plentiful jewels. Having wealth or jewels in that instance comes about through engaging in the practice of generosity; however, that individual hasn't engaged correctly in the practice of the protection of morality, therefore hasn't achieved the status of humans or gods (that is to say the realms of bliss) through the very fact of not protecting the cause, that is, ethical behaviour. So through contemplating these things we can come to see how the precious human existence which we now have in our hands is something which is not only more useful than a wish-fulfilling gem, but is also something which is incredibly difficult to come by.

Contemplation on Death

So then through these contemplations of one's precious human existence, one abandons all non-beneficial action. Then through contemplating how difficult it is to find such a human existence, one will seek out what will take the essence of this precious human existence, that is to say, one will put a lot of effort into engaging in the practice of the Dharma through seeing that one has in one's hands the incredible opportunity to make use of this life, and then the preciousness of one's life won't be carried off by the thief of laziness. So here we have to understand that this precious human life which we have is not something which is going to last forever - at some point there is going to be the separation of the mind and the body.

So when we talk about having a life-force within us, this life-force is basically referring to one's physical body and one's mind being joined together, so that when this joining of these two aggregates is broken, this is what is known as 'death', or the separation of the life-force. So when this occurs, one's physical form remains and is buried or whatever and then aggregate of consciousness goes on to one's future existence. So this is what is meant by 'death', and this is something which is definitely going to happen to all of us.

Now death is something which is definitely going to happen to all of us, but the time of our death is something which is not sure, not definite. If it were definite then we could mark it on the calendar and then just practice a bit beforehand, but however that is not the case - we could pass away at any time. So this being the case, we should really strive to engage in the practice of the Dharma while we have the chance to do that.

Then the third contemplation on death is that nothing is of any use to us at the time of death apart from the amount of time we have engaged in the practice of the Dharma. The reason for this is if we look at our predicament - when we are dying, no matter how rich we are, all our wealth gets left behind; no matter how many friends or associates we have, they all get left behind; even our body which we have striven so hard to protect and adorn and make look beautiful - this at the time of death gets left behind; and all that goes on to the future existence is the aggregate of one's mind and the amount of positive potential and Dharma practice which one has imprinted upon the aggregate of one's consciousness. So then we should contemplate that not only do we have this precious human existence which is difficult to find and has great meaning, but we should strive to put this into use through contemplating the great purpose of human life and how difficult it is to achieve that, through contemplating that we are definitely going to die, that the time of our death is uncertain, and that the only thing that will be of any use to us at the time of death is how much Dharma practice we have done in our life.

So the second line then:

There is no time to waste;

reverse attraction to this life…

So here what we are advised to do is to engage in the practices which we have gone through - contemplating the preciousness of one's human existence, how it is something difficult to come by and has great meaning and that it is not something which is going to last but rather is something that is at some point going to pass away. So through these contemplations, we come to the state of reversing attraction to this life. The sign of this is that we do not engage in any worldly actions, that is to say, actions which will bring about a result in this life, rather we are striving to utilise all our time to generate positive potential and positive Dharma training that will be of use to us in future lives. So once that has been developed fully within us, we can be said to be on our way with the practice which is in common with an individual of lesser capacity. Then we should try to emulate the great Kadampa geshe Potowa who used to spend all his time engaged in the practice of meditation or explaining the Dharma or engaging in different kinds of practice. He was continually meditating, reading Dharma, explaining the Dharma - he wasn't an individual like us who runs around doing this and that, but rather had just put his mind solely into Dharma practice, so we should strive to emulate such an individual.

Contemplation on the Karmic Law

So then the text goes on to tell us to:

reverse attraction to future lives;

think repeatedly of the infallible effects of karma

and the misery of this world.

So then one has a human existence now; if one turns one's attention away from this life and directs it towards one's future lives, the very best one can hope to achieve is another human existence like the one we have now or perhaps birth as a god or as a demigod (thus the three realms of bliss, or three higher realms). But if we investigate those three higher realms, they are not something which is stable, that is to say, they are not going to last for a long time - even having been born in those states we will inevitably fall from those states when the time of our death comes.

So the way we can reverse attraction towards, or thinking solely about, one's future existence is thus through contemplating the karmic law, that is to say, the law of cause and effect. So here this is a very profound subject, something which is quite difficult to go into great detail upon in such a short space of time, but if we go through the outline of four. Initially we should understand that karma, or action, is something which is definite, its increase is also something which is definite, and then one will not get certain results, for example a positive result, unless one engages in a positive action, that is to say the cause of such a result, and one won't get a result from which one hasn't planted the cause for its arising.

So if we look at this outline of four serially: Initially then that karma, or action, is definite. This means that if we engage in a positive action it is definite that the result of such an action, or such a karma, will be something positive. For example our human life now is the result of engaging in a positive cause in a past existence, and thus this is the ripening effect of that cause. Now the doubt can come - if someone is born as a human and is continually ill or undergoes a great amount of difficulty in their life, then we might feel 'well, that person is born as a human which, you say, is the result of a positive action; however, their human existence is not anything particularly joyous, anything particularly blissful - so how can that be the result of a positive cause?' So here we should understand a distinction between the different kinds of causes and the different kinds of results of those causes. The very fact that a sick individual has a human body is the result of a positive seed which was planted sometime in a previous existence. However, the various difficulties that this individual undergoes are not the result of the same cause, they are rather the results of different causes, or different karmas. That is to say, that individual has not only committed positive actions in the past, but has also committed negative actions, the ripening results of which are manifest as various difficulties, that is to say, illness etc.

So we can also understand this in reverse - if we look at certain kinds of animals, for example, dogs and cats - even though they are members of what we call the animal kingdom, or are included in the lower realms of existence, then they can still have the results of having committed positive causes in a previous existence. For example, we see dogs that are very, very beautiful, have very beautiful barking, cats that have very beautiful purring and so forth, very beautiful fur, very beautiful tails etc. So these results are not the results of negative causes, or negatives karmas, but rather are the result of positive causes, even though the basis for their ripening is an inferior one which is brought about through a negative karmic action, or a negative cause.

Then the second part of the outline is that karmas, or actions, once committed, increase. We can learn this through a very simple worldly example - if we plant a seed, the result of that seed can be something as huge as a great tree and yield lots of fruit. So a huge tree comes about through a tiny seed and in the same way a small action can bring about a great result, whether it be positive or negative. We read in the biography of the Buddha that a child threw some grains into the Buddha's begging bowl when the Buddha was walking past. Obviously the child couldn't just reach up and put them in the bowl because he was just a child and the Buddha was an adult, so there was a great difference in height. But even through throwing these grains, it is said that four of the grains fell in the begging bowl and one fell on the circular rim of the bowl, and even though this cause was something very, very small, it is said that the result of this was that the individual was born as a wheel-turning king with complete power over the four continents. So even from a small karmic action such as that, the result is something which is much, much bigger and this is explained clearly in the sutras.

Then the latter two of the outline of four are that if one hasn't generated certain causes then one won't experience the result of those causes, and the opposite - if one has accrued certain causes then one will definitely receive the result of those causes. So here then if one engages in a virtuous action then the result of that is something definite which will come to one and vice versa - if one has engaged in a negative action then the result of that is certain to come to one no matter what one's circumstances. We can still see this through an example given in the sutras: When the Sakya lineage of India (that which the Buddha belonged to) were destroyed, all wiped out simultaneously, two of them were hiding in a field, and it is said that even though they were far away from the battleground, owing to the light of the sun, the field caught fire and they perished in the fire. So the Buddha was asked about this: 'These two people who escaped from the battleground then went to this field to hide - how is it that they died at the same time that the Sakya clan was wiped out?' He explained that even though they weren't in the actual battleground, then they still had a similar karma to die at that particular time. So we can see various stories which give us solid examples of how that if we have accrued certain kinds of causes, their effect is definitely going to occur at that time unless that karma is exhausted in some way.

This brings us to the fourth of the outline of four which is that karma in and of itself never goes to waste, that is to say, it doesn't grow rotten and then suddenly disappear in and of itself, rather it is something that stays with us unless it is destroyed. So here then we have the understanding that karma is not something which we have to undergo - we can, if we apply the right antidotes, rid ourselves of these particular positive or negative karmic actions. So as it said then, the only good thing about bad karma is that is can be removed from our mindstream, or from our being. For example if we engage in the practice of love, this is the antidote to anger, and the reverse is quite the same - if we generate anger, this is the thing which destroys love ie virtuous states of mind. So if we have accrued a great amount of positive potential, or karma, this can be destroyed in a moment of anger. And with regard to negative states of mind which we may have generated in the past, if we engage in the opponent powers practices of regretting and then applying the various methods of confession and so forth, we can rid ourselves of these negative karmic seeds which we have in our being since we have accrued them in the past.

So the stanza then tells us to also reflect upon the misery of this world, or the cycle of existence, but tomorrow in the section on compassion, we will engage in the contemplation on the misery of the cycle of existence, so there's no need to go into this now. So if you have a question or two?

Question: I wanted to ask about collective karma. Rinpoche talked a bit about karma but how is it that one karma over-rides and brings a whole group of people to one disaster out of all the karma that there could be?

Rinpoche: With regard to the understanding of karma for an individual - if we understand this well, we will understand that through engaging in positive causes a positive result comes about, and the same for engaging in destructive karmic actions or causes - the result of that will be something unpleasant. So it is not that a group of people collectively engages in one particular action and then goes on to another action, but rather if we understand that through engaging in a positive cause, a positive effect comes around, not only for ourselves but if say everyone in the room has generated a similar cause in the past then the result for all of us can ripen at the same time. It's not that a group has to create a cause as a group, and then kind of all gather back and, as another group, have that result. For example, if we look at time - now we are in the time of the five degenerations, so it's not that we were all in some previous existence engaging in a particular action and the particular result of that is now undergoing the time of the five degenerations; but rather it is that we have engaged in various kinds of negative actions in the past, the result of which - the time of the five degenerations - is being experienced by all people, albeit in slightly different ways.

Question: I have a question for Rinpoche about renunciation. Here in the West we like to have comfortable homes, we have nice clothes, things like that, so I ask how we can practice renunciation without giving up all these things? [Big laugh from class!]

Rinpoche: It's very important to have a sense of satisfaction with oneself, that is to say, if we in general look at the way we behave, if we have some kind of enjoyment, we are always looking to better that enjoyment. If we are wearing some kind of particular clothing, we are always seeking something which is more beautiful, if we have some delicious food, we are always looking for something to match that or better that food. So our mind is not something very content at this point, so it's very important to develop a content and peaceful mind which is looking at one's enjoyments in a realistic fashion. That is to say, whatever we get, be it the very best, we are never going to be satisfied with that if we engage in desire for perfect objects, or beautiful objects - we are always going to try to find something which is better than what we have at the moment. With relationships, having friends, be they Dharma friends or whatever, when we come together, there is always going to come a time at the end when we disperse; and, for example, with our body, we have perfect human existence now, but this is not something which is going to last, it is something which is going to pass out of existence. So if we have a mind which is attached to and desirous of better and better objects, we are always going to be within a state of dissatisfaction, so a mind of satisfaction is something that is extremely important to develop, and more will be said about this in tomorrow's session.

So before tomorrow's session it would be excellent if you could contemplate the subject matter which we have gone through today. I have received this teaching many, many times from many high and extremely realised masters and they in return have received this from their teachers and thus we can trace the lineage back to Buddha himself. So through the blessing of the lineage there is definitely some benefit to be derived from engaging in these contemplations. Whether there is any direct benefit coming from me or not, there is doubt with regard to that, but with regard to the blessing of the lineage, as I mentioned I have received this teaching many times from many highly realised lamas, so remembering their instructions, I am imparting them to you. So if you could engage in the practice of contemplation on the subject matter, that would be excellent.

Searching for happiness

Searching for happiness The wisdom and form bodies of a buddha

The wisdom and form bodies of a buddha