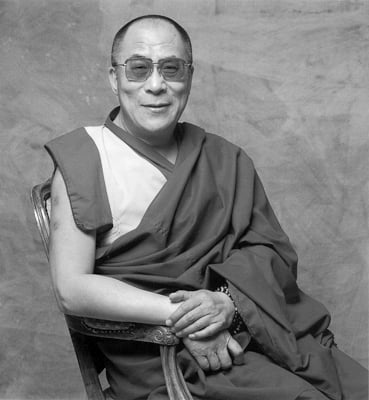

| His Holiness the Dalai Lama gave this teaching in Dharamsala, 7 October 1981. It was translated by Alexander Berzin, clarified by Lama Zopa Rinpoche, edited by Nicholas Ribush and first published in the souvenir booklet for Tushita Mahayana Meditation Centre's Second Dharma Celebration, November 5-8 1982, New Delhi, India.

Published in 2005 in the LYWA publication Teachings From Tibet. |

When the great universal teacher Shakyamuni Buddha first spoke about the Dharma in the noble land of India, he taught the four noble truths: the truths of suffering, the cause of suffering, the cessation of suffering and the path to the cessation of suffering. Since many books contain discussions of the four noble truths in English, they (as well as the eightfold path) are very well known.1 These four are all-encompassing, including many things within them.

Considering the four noble truths in general and the fact that none of us wants suffering and we all desire happiness, we can speak of an effect and a cause on both the disturbing side and the liberating side. True sufferings and true causes are the effect and cause on the side of things that we do not want; true cessation and true paths are the effect and cause on the side of things that we desire.

The truth of suffering

We experience many different types of suffering. All are included in three categories: the suffering of suffering, the suffering of change and all-pervasive suffering.

Suffering of suffering refers to things such as headaches and so forth. Even animals recognize this kind of suffering and, like us, want to be free from it. Because beings have fear of and experience discomfort from these kinds of suffering, they engage in various activities to eliminate them.

Suffering of change refers to situations where, for example, we are sitting very comfortably relaxed and at first, everything seems all right, but after a while we lose that feeling and get restless and uncomfortable.

In certain countries we see a great deal of poverty and disease: these are sufferings of the first category. Everybody realizes that these are suffering conditions to be eliminated and improved upon. In many Western countries, poverty may not be that much of a problem, but where there is a high degree of material development there are different kinds of problems. At first we may be happy having overcome the problems that our predecessors faced, but as soon as we have solved certain problems, new ones arise. We have plenty of money, plenty of food and nice housing, but by exaggerating the value of these things we render them ultimately worthless. This sort of experience is the suffering of change.

A very poor, underprivileged person might think that it would be wonderful to have a car or a television set and, should he acquire them, would at first feel very happy and satisfied. Now, if such happiness were permanent, as long as he had the car and the TV set he would remain happy. But he does not; his happiness goes away. After a few months he wants another kind of car; if he has the money, he will buy a better television set. The old things, the same objects that once gave him much satisfaction, now cause dissatisfaction. That is the nature of change; that is the problem of the suffering of change.

All-pervasive suffering is the third type of suffering. It is called all-pervasive [Tib: kyab-pa du-che kyi dug-ngäl—literally, the suffering of pervasive compounding] because it acts as the basis of the first two.

There may be those who, even in developed countries, want to be liberated from the second suffering, the suffering of change. Bored with the defiled feelings of happiness, they seek the feeling of equanimity, which can lead to rebirth in the formlessness realm that has only that feeling.

Now, desiring liberation from the first two categories of suffering is not the principal motivation for seeking liberation [from cyclic existence]; the Buddha taught that the root of the three sufferings is the third: all-pervasive suffering. Some people commit suicide; they seem to think that there is suffering simply because there is human life and that by ending their life there will be nothing. This third, all-pervasive, suffering is under the control of karma and the disturbing mind. We can see, without having to think very deeply, that this is under the control of the karma and disturbing mind of previous lives: anger and attachment arise simply because we have these present aggregates.2 The aggregate of compounding phenomena is like an enabler for us to generate karma and these disturbing minds; this is called nä-ngän len [literally, taking a bad place]. Because that which forms is related to taking the bad place of disturbing minds and is under their control, it supports our generating disturbing minds and keeps us from virtue. All our suffering can be traced back to these aggregates of attachment and clinging.

Perhaps, when you realize that your aggregates are the cause of all your suffering, you might think that suicide is the way out. Well, if there were no continuity of mind, no future life, all right—if you had the courage you could finish yourself off. But, according to the Buddhist viewpoint, that’s not the case; your consciousness will continue. Even if you take your own life, this life, you will have to take another body that will again be the basis of suffering. If you really want to get rid of all your suffering, all the difficulties you experience in your life, you have to get rid of the fundamental cause that gives rise to the aggregates that are the basis of all suffering. Killing yourself isn’t going to solve your problems.

Because this is the case, we must now investigate the cause of suffering: is there a cause or not? If there is, what kind of cause is it: a natural cause, which cannot be eliminated, or a cause that depends on its own cause and therefore can be? If it is a cause that can be overcome, is it possible for us to overcome it? Thus we come to the second noble truth, the truth of the cause of suffering.

The truth of the cause of suffering

Buddhists maintain that there is no external creator and that even though a buddha is the highest being, even a buddha does not have the power to create new life. So now, what is the cause of suffering?

Generally, the ultimate cause is the mind; the mind that is influenced by negative thoughts such as anger, attachment, jealousy and so forth is the main cause of birth and all such other problems. However, there is no possibility of ending the mind, of interrupting the stream of consciousness itself. Furthermore, there is nothing intrinsically wrong with the deepest level of mind; it is simply influenced by the negative thoughts. Thus, the question is whether or not we can fight and control anger, attachment and the other disturbing negative minds. If we can eradicate these, we shall be left with a pure mind that is free from the causes of suffering.

This brings us to the disturbing negative minds, the delusions, which are mental factors. There are many different ways of presenting the discussion of the mind, but, in general, the mind itself is something that is mere clarity and awareness. When we speak of disturbing attitudes such as anger and attachment, we have to see how they are able to affect and pollute the mind; what, in fact, is their nature? This, then, is the discussion of the cause of suffering.

If we ask how attachment and anger arise,3 the answer is that they are undoubtedly assisted by our grasping at things to be true and inherently real. When, for instance, we are angry with something, we feel that the object is out there, solid, true and unimputed, and that we ourselves are likewise something solid and findable. Before we get angry, the object appears ordinary, but when our mind is influenced by anger, the object looks ugly, completely repulsive, nauseating; something we want to get rid of immediately—it appears really to exist in that way: solid, independent and very unattractive. This appearance of “truly ugly” fuels our anger. Yet when we see the same object the next day, when our anger has subsided, it seems more beautiful than it did the day before; it’s the same object but it doesn’t seem as bad. This shows how anger and attachment are influenced by our grasping at things as being true and unimputed.

Thus, the texts on Middle Way [Madhyamaka] philosophy state that the root of all the disturbing negative minds is grasping at true existence; that this assists them and brings them about; that the closed-minded ignorance that grasps at things as being inherently, truly real is the basic source of all our suffering. Based on this grasping at true existence we develop all kinds of disturbing negative minds and create a great deal of negative karma.

In his Entering the Middle Way [Madhyamakavatara], the great Indian pandit Chandrakirti says that first there’s attachment to the self, which is then followed by grasping at things and becoming attached to them as “mine.”4 At first there is a very solid, independent I that is very big—bigger than anything else; this is the basis. From this gradually comes “this is mine; this is mine; this is mine.” Then “we, we, we.” Then, because of our taking this side, come “others, our enemies.” Towards I and mine, attachment arises. Towards him, her and them, we feel distance and anger; then jealousy and all such competitive feelings arise. Thus ultimately, the problem is this feeling of “I”—not the mere I but the I with which we become obsessed. This gives rise to anger and irritation, along with harsh words and all the physical expressions of aversion and hatred.

All these negative actions (of body, speech and mind) accumulate bad karma.5 Killing, cheating and all similar negative actions also result from bad motivation. The first stage is solely mental, the disturbing negative minds; in the second stage these negative minds express themselves in actions, karma. Immediately, the atmosphere is disturbed. With anger, for example, the atmosphere becomes tense, people feel uneasy. If somebody gets furious, gentle people try to avoid that person. Later on, the person who got angry also feels embarrassed and ashamed for having said all sorts of absurd things, whatever came into his or her mind. When you get angry, there’s no room for logic or reason; you become literally mad. Later, when your mind has returned to normal, you feel ashamed. There’s nothing good about anger and attachment; nothing good can result from them. They may be difficult to control, but everybody can realize that there is nothing good about them. This, then, is the second noble truth. Now the question arises whether or not these kinds of negative mind can be eliminated.

The truth of the cessation of suffering

The root of all disturbing negative minds is our grasping at things as truly existent. Therefore, we have to investigate whether this grasping mind is correct or whether it is distorted and seeing things incorrectly. We can do this by investigating how the things it perceives actually exist. However, since this mind itself is incapable of seeing whether or not it apprehends objects correctly, we have to rely on another kind of mind. If, upon investigation, we discover many other, valid ways of looking at things and that all these contradict, or negate, the way that the mind that grasps at true existence perceives its objects, we can say that this mind does not see reality.

Thus, with the mind that can analyze the ultimate, we must try to determine whether the mind that grasps at things as truly findable is correct or not. If it is correct, the analyzing mind should ultimately be able to find the grasped-at things. The great classics of the Mind Only [Cittamatra] and, especially, the Middle Way schools contain many lines of reasoning for carrying out such investigation.6 Following these, when you investigate to see whether the mind that grasps at things as inherently findable is correct or not, you find that it is not correct, that it is distorted—you cannot actually find the objects at which it grasps. Since this mind is deceived by its object it has to be eliminated.

Thus, through investigation we find no valid support for the grasping mind but do find the support of logical reasoning for the mind that realizes that the grasping mind is invalid. In spiritual battle, the mind supported by logic is always victorious over the mind that is not. The understanding that there is no such thing as truly findable existence constitutes the deep clear nature of mind; the mind that grasps at things as truly findable is superficial and fleeting.

When we eliminate the disturbing negative minds, the cause of all suffering, we eliminate the sufferings as well. This is liberation, or the cessation of suffering: the third noble truth. Since it is possible to achieve this we must now look at the method. This brings us to the fourth noble truth.

The truth of the path to the cessation of suffering

When we speak of the paths common to the three vehicles of Buddhism—Hinayana, Mahayana and Vajrayana—we are referring to the thirty-seven factors that bring enlightenment. When we speak specifically of the paths of the bodhisattvas’ vehicle [Mahayana] we are referring to the ten levels and the six transcendent perfections.7

We find the practice of the Hinayana path most commonly in Thailand, Burma, Sri Lanka and so forth. Here, practitioners are motivated by the desire to achieve liberation from their own suffering. Concerned for themselves alone, they practice the thirty-seven factors of enlightenment, which are related to the five paths: the four close placements of mindfulness, the four miraculous powers and the four pure abandonments (which are related to the path of accumulation); the five powers and the five forces (the path of preparation); the seven factors of enlightenment (the path of seeing); and the eightfold path (the path of meditation). In this way, they are able to completely cease the disturbing negative minds and attain individual liberation. This is the path and result of the Hinayana.

The primary concern of followers of the Mahayana path is not merely their own liberation but the enlightenment of all sentient beings. With this motivation of bodhicitta—their hearts set on attaining enlightenment as the best means of helping others—these practitioners practice the six transcendent perfections and gradually progress through the ten bodhisattva levels until they have completely overcome both types of obscurations and attained the supreme enlightenment of buddhahood. This is the path and the result of the Mahayana.

The essence of the practice of the six transcendent perfections is the unification of method and wisdom so that the two enlightened bodies—rupakaya and dharmakaya—can be attained. Since they can be attained only simultaneously, their causes must be cultivated simultaneously. Therefore, together we must build up a store of merit—as the cause of the rupakaya, the body of form—and a store of deep awareness, or insight—as the cause of the dharmakaya, the body of wisdom. In the Paramitayana, we practice method grasped by wisdom and wisdom grasped by method, but in the Vajrayana we practice method and wisdom as one in nature.8

Notes

1. See, for example, Tsering, Geshe Tashi. The Four Noble Truths. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2005. Also: Gyatso, Lobsang. The Four Noble Truths. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 1994. [Return to text]

2. The five aggregates [Skt: skandha]—one physical and four mental—are the elements that constitute a sentient being of the desire and form realms. Beings of the formless realm have only the four mental aggregates. See Gyatso, Tenzin. Opening the Eye of New Awareness. Boston: Wisdom Publications, p. 33. [Return to text]

3. See Yeshe, Thubten, and Zopa Rinpoche. Wisdom Energy. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1995, Chapter l: “How Delusions Arise.” [Return to text]

4. See Rabten, Geshe. Echoes of Voidness. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1983, Part 2. [Return to text]

5. See Opening the Eye of New Awareness, p. 43 ff., for details of the ten non-virtuous actions of body, speech and mind. [Return to text]

6. See Gyatso, Tenzin. The Buddhism of Tibet. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 1987. [Return to text]

7. See Hopkins, Jeffrey; Meditation on Emptiness: Wisdom Publications, 1983. [Return to text]

8. See His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s introduction to Tantra in Tibet. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 1987, for a detailed explanation of method and wisdom in sutra and tantra. [Return to text]