So I think we are a bit early, five minutes early.

[Background noise] It’s a bit loud.

Okay, so first of all, I would like to thank you all for being in the November course. I think it’s very, very special that all of you have come from all over the world, from so many different places to meet here. It’s a very special occasion and a huge opportunity for all of you to also connect with everybody else. So I just wanted to thank you for making that effort of coming over here and learning some Dharma, and making the connections.

Sorry for the breathing. [Loud noise in background] How do you do it Gyatso-la? How do you breathe?

[Ven Gyatso/Adrian: Just bend it out a bit.]

[Microphone adjustment] Hello? Yeah, that’s better. Now I can breathe!

So first I just wanted to mention the translators. How many translators are there? Three? Four? So I’m going to try to talk a little bit slowly if that’s okay. If I’m going too fast, just let me know, okay? Thank you.

So let us start with gratitude, first of all. Gratitude for the body we have, which was given by our parents. Gratitude for the food we are able to eat, and for the shelter we have every day, which many people don’t have. So let us also have gratitude for this space which we are sharing right now.

So let’s have a minute of silence in gratitude for all those precious things that are ours. Because actually, the only thing that we actually own is our body, and the moment comes with that. So let us feel appreciation for that. So minute of silence. [meditate]

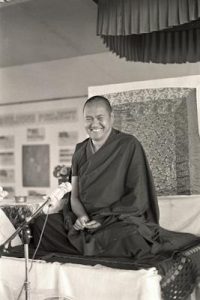

So first of all, I would like to start introducing myself because I think many of you probably don’t know who I am or what my history is. So I think it’s important to explain a little bit why I’m sitting here right now.

So basically, I grew up in a monastery in India, in South of India. Since I was six, I grew up in the monastery ‘til I was seventeen or eighteen.

So I had a lot of contact with Buddhism and the tradition because I was a monk. So basically, I felt it was important also to talk a bit from my own experience of what Buddhism is like for me, so that I could help many of the new people who have not had much contact with Dharma, and also being it’s their first time, so it can be sometimes a bit heavy and difficult to understand. But in the end, it will be very easy because it’s very simple. It’s just sometimes, it can get complicated, but you can simplify it always. So don’t worry about that.

So when I was around sixteen years old, fifteen, sixteen, because most of my life I had believed I was a Buddhist, because I grew up in that ambiance. And then when I was fifteen, sixteen, I read the book called Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse. I don’t know if you’ve read it but you should if you can. It’s really good.

And after reading that book, I really questioned myself and I said, “Am I really Buddhist?” How can I be a Buddhist if I don’t quite understand yet the Buddhist philosophy and what Buddhism really is? So then I started to realize that maybe actually I was still learning to be a Buddhist. So therefore, I was like in the process of becoming a Buddhist.

And I believe I still am today. I’m twenty-seven. It’s been already ten years and I’m still in the process of becoming a Buddhist. So it’s not something that just happens from one day to another Being Buddhist is not about just reading book or going to courses, taking meditation or initiations. It’s also about the lifestyle, the attitude you have, the way you think, the way you act, the way you talk. So that’s basically one of the important parts of being a Buddhist.

So for me it’s been like that. And I think it’s, it may be helpful if I can share a little bit my small thoughts with all of you because I understand it can be hard sometimes to understand the traditional way.

Of course, the tradition is super important because it’s something that has come from many, many generations, thousands of years of people practicing and having realizations and understanding, and passing it on to the next generations.

So that’s why tradition is super important. It’s there, and it’s available. It doesn’t mean it will work for everybody. Each person has to find their own way of understanding and what works for them because nobody can really come and say, “Okay, I found the truth. Take it.” It may be his truth, but it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s your truth. You have to find your own truth.

Somebody can come and help you to find that. And that’s what Dharma is for. The guru is also. The guru, the teacher, is helping you to find your own way, your own self, investigating inside and understanding the nature of the mind. That is the guru and the Dharma.

But ultimately, the real guru is inside ourselves. We are our own guru, we are by ourselves. So it’s up to us to walk the path, always. We are born by ourselves in this body, and we will die by ourselves. There will be nobody who will take care of us afterwards in the sense like holding our hands and carrying us. We have to walk the path by ourselves.

They will help us, of course. It’s like being in the middle of a forest in the night. [pause] Am I going too fast? [Asking translators?] Sorry. It’s like being in the forest at night and it’s completely dark. So you’re trying to get out of the forest. But you don’t know which direction to take.

And then suddenly, the full moon comes out and then the full moon helps you to see a little bit better. So then you can see better and you can maybe climb a tree and see where, which direction you want to take. So then basically we’re trying to get out of the forest. We’re not going to the moon. The moon helps us to get out of the forest.

So that’s a little bit like the metaphor I like to use with Dharma and gurus. Because many people think the guru is salvation. No. The guru will help you to understand our own nature, but that’s not salvation. Salvation is in ourselves. And the further away we search from ourselves, the further away we are from ourselves and the harder it is to find that.

So I just wanted to make a point, there before I started because I have struggled with that for a long time. So I think… and also it’s just my point of view, so it doesn’t mean it’s the truth or anything. You just take what you feel works for you, what you like, and what you don’t think works for you, just leave it – it’s not that important for you. Each person is different, right?

Like for example, when you’re walking on the beach and you see the ocean, the sea, and the sun is coming down and you see the reflection of the sun coming towards you. It’s like a path from the sun to you. And what you see shining is what you see shining. But somebody else who’s over on the other side will see their own shining, their own path.

Actually, the whole ocean is shining but we only see one small part which is from the sun to us. And what we have seen, the shining, the other person cannot see because they’re in another place. So we have to walk to where they are to see the same shining, right? I’m sure you have seen that before. And sometimes when you go in the plane, you can see the whole ocean shining, which is how it normally is.

So that’s just like a metaphor to understand that each of us is different as individuals. Each grain of sand in the ocean is different. So you can never really compare, and you can’t really judge other than judge yourself because we are the only ones who really know ourselves, and we really know where we are or what we’re doing. So that’s why it’s important to try not to judge. And if you have to judge, then at least don’t condemn because we can all change.

So the November course is about Buddhism. And I wanted to start talking about samsara.

Many of you know probably already what samsara is. According to Buddhism, samsara is like the wheel, it’s a wheel of.., where we are born and we die again, and we are stuck in this wheel of constant rebirth and just going around and around.

So Dharma is here to help us to be liberated from that, even though that’s very far away still. We have to concentrate on the now, right? So it’s important to, that’s the concept of samsara.

So the purpose of Dharma is to help oneself in order to help other people. And that way we find our own purpose because, basically [if] we think about the animals on this planet, their purpose is to survive and to reproduce. And we are like animals also. The only difference is that we have many different capabilities or capacities. We’re able to think, we’re able to speak, so many, each of you[know already. We’re all human beings.

So apart from, of course, surviving and reproducing, we have many other purposes. But of course, the main purpose is to help ourselves, to understand ourselves so that we can help other people do the same. And as we can see today in the planet, it’s complete chaos. People who think they are happy, they’re actually suffering much more than the people who think they are suffering.

There’s a saying that I like. It says, “Some people are so poor that all they have is money”, which is not so far from the truth.

So in this world, sometimes it can be really hard for some people, and we have the opportunity to be in contact with the Dharma, which can help us a lot. There are many other different ways of finding our true nature and understanding it – and one of them is Dharma.

So we are all here, and that’s a good thing, it’s a really good thing. So, if some of you sometimes feel it’s difficult to understand, don’t worry, it’s easy, ultimately it’s easy, even though there’s things because of tradition, may become complicated but that’s up to you to filter what works for you because for each person it’s different.

So because Gyatso’s talking, Venerable Gyatso’s speaking about karma yesterday, and so one of the important things of karma is the intention behind it. The intention is so important because that’s the main thing that is behind our actions and our thoughts and speech. So that’s why it’s really important to always check oneself. Before you check someone else, check with yourself. Because many people, many times, we tend to just judge other people and not really look at ourselves. “Oh this person is doing that, he’s saying this, blah, blah, blah”. But then we don’t really look at ourselves. And then, we forget about what we are doing. So it doesn’t really make sense, right?

So that’s why it’s so important to check oneself and see really what our intention is. Because based on our intention, then the karma comes from there. If the intention is positive, then the karma is positive; if the intention is negative, then the karma will be negative.

I mean, I can’t really show you that karma exists. I didn’t believe in reincarnation for a long time; and karma was one of the things that I didn’t believe in. I used to call myself ‘agnostic scientific’. And then I added ‘spiritual’ afterwards. I was never an atheist because you never know what really is out there. You know what your own world is, from your eyes, what you live. But there’s so much out there.

When you go to another city and you see everybody just moving around, you’re like, “Wow, this exists all the time”. It’s just that I’m here right now and I’m seeing it now. But even if I’m not here, it’s still happening. So what we think, is not everything that is. What we see is not everything; it’s part, it’s a small part. So that’s why you always have to be open also, not like closed doors and say, “No, that’s not true”, or “That doesn’t exist”, because it may very well exist; you never know.

And so for a long time, I didn’t believe in karma, and then slowly, slowly I started to understand that karma is a little bit like the law of the universe; it’s like physics, it’s a type of law. So karma is another law. It’s so subtle, it’s very hard to see. But from generation to generation people have experienced it, and that’s what we have today. It’s the teachings of the Buddha that have been carried on to many generations.

So if you don’t believe it, you can check. But it makes sense, and it’s very logical because karma is like the law of cause and effect. What you give, you will receive eventually. And even if you don’t believe it, I think it’s pretty logical because sometimes you question yourself, “Why are these people suffering? They didn’t do anything”. So there must be a reason why. And for me, I think it’s the most understandable explanation to that.

So behind our intentions and our choices, which are very important of course, because every day we make choices, our emotions sometimes they guide us towards those choices.

One of the things, I think Dharma tries to help us is to not become slaves to our emotions because there are many different emotions. There’s the negative ones and the positive ones. The negative ones, for example, anger or jealousy or different very negative emotions, sometimes create more negative energy.

Like, for example, anger. When you get angry you go blind a little bit. And then from that, then you can do some actions which later on will cause a lot of suffering to yourself and to other people because you were blind at that moment and you became a slave to that emotion.

So you have to really be careful with some emotions because when you do become a slave, that creates an energy and a reaction. So it’s always better if you have emotions, to have positive emotions; try to control the negative emotions.

It doesn’t mean that those emotions are not going to be part of us, like, for example, anger. I can be an angry person, right, even if I don’t look like it right now. But sometimes when it comes out, then it comes out , yeah? It doesn’t mean I’m not angry, like I’m not an angry person. It’s inside. This has to be a catalyst that will make it come out.

So it’s not like we can banish anger, but we can – or maybe you can, I don’t know. Eventually, I think, Dharma can help you with that. But I think mainly it’s to try to control that emotion and try to be aware of where it’s coming from.

Like when you start getting angry, then you say, “Oh, this is happening”. Then you try to breathe, try to rethink, try to understand where it’s coming from, investigate, observe, and then slowly, the anger will disappear. So that’s like a very good, one of the first steps in order to try to keep the negative emotions at bay, because the negative emotions are a big thing about karma – they can create a lot of bad karma. So we have to really check that.

So sometimes the emotions can create an attitude or a state of mind. We have a thought, then from that, there comes an attitude. Then because maybe we are stressed, somebody comes, and that person is talking to us very nicely but because we are stressed or we are pissed or whatever, then we talk really badly to them. We don’t, kind of pay attention, and we just…. So that sometimes is something that we really have to be aware.

If you are stressed, and it’s hard for you to not to be angry with the person, then that’s the test. That’s when you can be the real Buddhist. Then if you can really control that and be a good person at that time, then that’s, you’re surely becoming a real Buddhist. Right.

Just cause you read a book or do some meditation, doesn’t mean you become a Buddhist – at least from my side. Each person has their own view, of course.

So it’s so important to be aware of our mind at all times because if you think about it, everything that’s been created by the human being – starting with the gompa, our clothes, the floor, the roof, the place, the buildings, everything – in one beginning, it started with a thought. Someone had to think of that before it started, before they started to create that. So just by looking, everything that’s been created by the humans, then you can already see how powerful the thought is.

So just because you’re the only one who knows what you’re thinking, it doesn’t mean that it’s okay to think bad things. I mean it’s, of course, it’s normal but sometimes it’s good to check why it’s coming, from where it’s coming and whether it’s beneficial for yourself.

For example, if you criticize someone, you’re actually harming yourself more than you’re harming the other person. You’re also harming the other person.

So that’s one of the things, it’s important now that we are alive and that we’re here, to try to be a better person. That’s basically what Dharma is telling us. And through that, we can really find happiness, because most of us, that’s what we’re searching – we’re searching for happiness.

And also I had a hard time with happiness because it’s so far away, like enlightenment, to become enlightened or to help all sentient beings. How can you help all sentient beings? That’s like almost impossible. I used to struggle with that every day. How can I be happy? Happiness. Where am I going to find happiness. I mean, it’s a state of mind.

So those things for me was really, really hard, and I found ways around it. So instead of ‘all sentient beings,’ it would be ‘some sentient beings,’ starting with yourself and your family and your friends, which is enough. And happiness, I also found it not being unhappy is easier than trying to be happy. So that’s like the first step.

When you’re trying not to be unhappy, then you make the cause for eventually to be happy. So that’s, at least for me, it’s easier to tackle when you think about it.

So that’s why, so there’s always many ways to see it and many ways to get around so that you can understand for yourself, because each person is different, like I said. And it’s normal that for some people it may work, for some people it may not work.

So I don’t want to take too much time because I know it’s, the day is very intense for all of you, and you are also doing in the November course, apart from the teachings there’s meditation, there’s what’s it called, writing sessions, discussion groups and dreaming, dream interpretations. I don’t know, there’s many different things which I really like to be part of. So I don’t want to take much of your time. Maybe we can repeat this again another day.

So basically, we’re looking for happiness. So if we try not to be unhappy, then we can create the causes slowly to be happy. And basically, how can we be happy is by helping other people to be happy, and that will come back to us.

So the more we try to be happy, the less happy we will be. And it works that way. If you try to be, try to buy a lot of stuff for yourself, the more stuff you buy, the less happy you will be because the stuff will never reach our expectations, and sometimes it will break, so we’ll be unhappy.

So if we actually search to make someone else happy, then we’ll be happy automatically. Just by seeing them, just the appreciation they give us, just the action. Even if they don’t appreciate, it doesn’t matter, we already did the action.

So the compassion, what we like is well-being, to live well. Sometimes, for example when we suffer, the suffering starts in one moment, let’s say something happens. There can be different types of suffering – physical suffering or mental suffering; sometimes the physical suffering is created by the mental suffering, like sometimes we can become sick because we are depressed all the time. So our body reacts to that. Our thoughts are very powerful, so they really affect us and they affect the people around us, too.

So what we really want to be, we search for the well-being, to be comfortable, to have food when we’re hungry, to have a nice bed to sleep, not to be cold, when we’re too hot, to have something nice breeze. So basically, if we’re able to help other people with that, then we are helping ourselves. Because ultimately, we are all just functional beings, right? Our function is to live. So if we live in a better way according to our own moral code, then we’ll be better people, and eventually we can really find that happiness eventually.

So it’s not so far away, but there’s first steps you have to take. Just like enlightenment. I used to think, “Wow, enlightenment is so far away, it’s impossible. How can we talk about enlightenment if it’s so far away?” But of course, you have to have your goal, you have to see where you want to go. Then if you know where you’re going, then slowly it will happen. But you have to know where you want to go.

So it’s a good thing to want to reach enlightenment one day. But of course, there’s many steps before. So we have to concentrate on the other steps. But always keep that in mind – that our purpose is to become enlightened, to be free from suffering and from samsara in order to help other people to reach that also. Basically that’s Buddhism; at least from my point of view, that’s Buddhism condensed in a sentence.

So compassion is so super important. We can talk about bodhicitta. Bodhicitta is one of the means to reach that goal, and karma is part of that. When you have compassion, then you create a very positive karma that will help you and help other people eventually reach that place.

So that’s basically what I wanted to share today. I hope it wasn’t too complicated. And I’m not sure if maybe we have time for questions and answers, but maybe we can do that another day unless, of course, there’s a microphone handy and people would like to ask questions.

Even though, personally I’m not qualified to answer Buddhist questions but I can try to answer the best I can. So I don’t know.

Ven. Gyatso: If people have questions, you can stand up and speak loudly.

Lama Osel: There’s no microphone? [One manifests] Oh, yeah, perfect!

I think for now, today, I think that’s good. Oh, many questions.

Questions and Answers

Question: Thanks for talking to us today.

Thank you.

Questioner: I have a problem with I can’t talk to a partner, or desire with people, that the monks maybe cannot explain about, so perhaps you can enlighten us on that topic.

Lama Osel: Yes, it’s very complicated. First of all, I think each couple is completely different because it’s two individuals, and each individual is so different, so that a couple makes it even more different, more unique. So each couple is so different, it’s really hard sometimes to really explain the situation for each couple. Of course, what goes between each couple is just between them, of course. And they are the ones who are learning through each other.

Personally I think living with a couple, with a partner is very helpful in order to learn, for example, patience or understanding, or empathy, or all these really good qualities can come from living with your partner, as long as you give space and you understand the other person, and you really try to listen to them and try to understand what they are going through, and also accept because each person is the way they are. And many times, at the times of the couple when we are together, [There’s music coming from close by], oh, beautiful Indian music. Maybe it’s supposed to go with the conversation, the couple conversation. Romantic music.

So when you’re living with someone, it can be very hard because many times we project what we would like the other person to be like. And of course, our projections never reach what reality is actually. Because there’s two different things: what we see is not the same as what there is.

For example, when I was maybe fourteen, fifteen, I used to have many zits in my face, green zits that come from puberty. So I used to see myself really ugly. And then maybe someone take a picture, and see the picture and be like, “Oh my god, I’m so ugly! I don’t like myself, at all”. And then maybe five, six years later, I would see the picture, and I’m like, “Wow, I’m so young! I look so good. I wish I could be like that now!”

So there you have a really good example of how the mind plays tricks on us, because the picture’s exactly the same. It’s just that I see myself different. I’m projecting what I would like to be like on both occasions. But the picture’s the same, the person in the picture is the same.

So that’s, I think it’s a good example to show that what we are seeing is not always what there actually is there, because what we see can change all the time. Maybe today we see something, then next year, it’s something different – even tomorrow or even maybe in an hour it can change.

But the thing there, it’s changing, of course, but it’s the same thing. I mean it’s changing, because the energy particles are moving constantly there, buzzing. But, actually, it’s solid. It looks solid, at least. Like next year, maybe the table will continue being the same, maybe the same color, but my mind will have been completely different. So our mind changes at a much greater speed.

So that, also in a relationship with your partner, that affects us a lot. And that’s I think, one of the root of the problems living, when you live with your partner is that many times you project, and you think you know the person or you understand the person, but actually what you understand is what you think you understand.

So it’s important sometimes to know how to differentiate those things. And that’s what Buddhism calls ‘dualism’. Now, I’m not sure. Is that correct? Kind of? Close. I’m still learning.

So when you live with a couple, it’s so important always to respect and to give space, and to try to understand. And when emotions, especially negative emotions come, to push them down, and then that’s a really good practice. So you can really evolve, fast, when you live with your partner if you know how to complement each other, how to complement each other in that sense.

And respect, of course, always, respect – is the most important, I think, factor. And understanding also. Try to understand that person as much as you can. Before you try to impose what you would like, or what you think is correct, try to understand what the other person is saying to you, and what they are trying to make you understand.

So then vice versa, it works really well. If you can really achieve that level, then you will evolve much faster ‘cause think that’s the best test of patience. Maybe parents and your partner?

In Asia, it’s not so much the parents, but I think in the West, it is ‘cause it can be really hard sometimes.

Yeah, so I hope I answered your question in an understandable way.

Any more questions?

Question: Dear Osel, What role do you think the internet, and social media have in spreading the Dharma, or at least raising mass consciousness? How can we make sure that we don’t become superficial activists? For example, just clicking on a link to save the whales and feeling good about that only.

Lama Osel: Oh, that’s a complicated question. But I think clicking is the first step, right? ‘Cause the computer is in our house or maybe we’re in cyber café, but at least it’s the nearest thing to trying to do that good action. So there’s also a first time, there’s always a first step. So clicking is good enough as long as your intention is there, right?

Then of course, other people maybe go to Africa to help the children there. Or maybe study medicine and then go to Africa and be a medic. Maybe other people will sponsor a child, and some people just click. I think either way, as long as your intention is pure, then it’s good enough. Because each person is different, and some people don’t have the time, don’t have the capacity or maybe the budget or the finance to do that.

Or even the, what do you call it when you do, when you really work hard at some things, the hardship. Like some people give up really easily, some people don’t. So dedication is the word I was looking for. Some people don’t have enough dedication, so it’s easier than other ways. So I think each person has to find their own method of trying to achieve that goal.

Question: So technology can be a great way to spread these beautiful ideas. But it can also be a source of addiction and attachment. And I wonder if you have anything to say about how we can use Dharma to not get attached, to like …

Lama Osel: Facebook.

Question: …the computer. Yes, Facebook, yes.

Lama Osel: Yeah, I know, I understand what you mean. Yeah, it’s true, sometimes the internet can create attachment, and just being connected all the time, you just, it’s like you spend so much time on internet sometimes that it can be difficult to really relate to the real world, our reality as a human being; it’s just the screen sometimes, that’s our reality.

Even for some kids, they’re playing game all the time, and that’s their reality. And then when they go out into society, they have difficulty relating to other people because they don’t feel comfortable with themselves, because they are so accustomed to just being themselves in the computer.

So that can happen also like with Facebook or with other computer-related programs or internet, internet-related programs.

I think it’s a question of, what do you call it, [pause] moderation. I think if you’re able to moderate, then it’s okay as long as you’re doing something useful, apart from passing the time, which most of us…. I think I pass a lot of time on Facebook or just looking at things, and just whatever.

But I think it’s important to have moderation and try to, as long as you’re spending your time, try to do it in a way that’s meaningful for you. I mean, you can spend, maybe an hour or two just doing nothing, because it’s important also to do nothing, to rest and to just be with yourself and relax. But don’t spend too much time doing nothing, ‘cause then you’ll be unhappy ‘cause you haven’t accomplished anything, and that’s one of the causes also of being unhappy.

Maybe bring the microphone to them if it’s possible. Sorry. It’s coming, okay?

Question: How can you use Dharma knowledge in our daily life in our relationship with parents, friends and partners, to give them some advice without sounding harsh, like saying, “It’s your karma, you’re so attached; it’s impermanence”?

Lama Osel: I think maybe examples are really good. When you use examples that relate to the people in everyday life, like for example impermanence – you can explain to that in the sense that just because you buy a new I-phone, it doesn’t mean you’re going to be happy. Right? You may be happy when you bring it from the shop to your house. “Woah, I got a new I-phone!” And then you get home, you unwrap it, or it can be anything. And then eventually, it will be something else. So that’s a good example for impermanence.

Or karma, it’s like also, for example, if what would you like people to do for you? If you want to be happy in the sense, if you don’t like someone to talk harshly towards you, then why would you talk harshly to someone else, for example, right? Because that creates, it’s not nice for you.

Or if someone hits you, you don’t like it. So why would you do that to someone else, right? You try to explain that in the first person, so that maybe they can relate to that in everyday life, using examples like that. I think it’s easier than just using the name ‘karma’ or ‘impermanence’ or ‘attachment’. Eventually you can use that, but you have to explain to them what it means, right? Otherwise they won’t really understand.

Question: I guess you own modern movies, and I would like to ask you what you think about Western society especially in case of sex, drugs, and rock ‘n roll? Look at the United States of America – some people say it’s like ancient Rome.

Lama Osel: Ancient Rome.

Question: Ancient Rome, it’s going down. Who will be the next leader?. What do you think?

Lama Osel: I think, first of all, we shouldn’t generalize, because each person is different. As an individual, each person makes their own choices. So just because a group of people do something, doesn’t mean everybody does it. So that’s, I think the first thing is not to generalize so much.

But I think it’s part of the culture, the Western culture, it has a long history of sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll. Of course, so it’s part of the culture in a way. And it’s also something interesting to experience in order to understand in deeper way what samsara means.

Because sometimes, for example, if, when you become a monk in Tibetan tradition at a very young age, and you take vows, and you give up things which you don’t even know what they are. Then eventually you have a curiosity and you will want to know what it is like. So I think for some monks, of course, it’s no problem. But for some monks it is a problem, because they want to understand, they want to know what that is. It’s like reading a book about chocolate and then, of course, you don’t really know what it is like to eat chocolate. But it doesn’t mean the chocolate is going to bring you happiness. Right? In the book, it says chocolate will not bring you happiness. But you want to know at least what it tastes like in order to know that it won’t bring you happiness.

So it doesn’t mean that everybody has to do that. It’s just that for some people it’s interesting to have gone through that. And for example, Kopan started with the hippies that came to Nepal, and then they were introduced to the Dharma. And because they had gone through that, they really appreciated Dharma, and they found it as something very helpful because they felt that their generation was getting a little bit lost with the sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll.

So as I said before, I think moderation is very important, and to learn from our mistakes and to learn from our experience, and to always try to be a better person.

And I think culturally, it’s part of the Western culture, also worldwide. It’s not something that is bad in a sense. Of course, without moderation, everything is bad, without the right intention. So you just, you try to keep that at bay and try to understand why, where it’s coming from, why it’s coming, why are we searching that. And that eventually that is not going to bring satisfaction.

I mean, you can look at all these famous singers from the 1970’s like Mick Jagger and Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix, and so many of them just passed away at a very young age. And just because they were experiencing that, doesn’t mean they’re going to be a better person. Of course it made great music, which may inspire people to be better people but it doesn’t mean that that is the answer.

So if you try it, try it in moderation and eventually understand where it comes from, and understand that that does not bring happiness. As a matter of fact, it brings more unhappiness.

Question: What do you think is Buddhism in the modern world, how does it translate, and is the modern Buddhism is keeping the essence of Buddha’s teachings.

Lama Osel: I think Buddhism came from thousands of years ago. So it’s important also to relate to Buddhism, today. Because people have changed, and sometimes tradition has stayed behind, it doesn’t mean it’s not useful; of course it’s useful, it’s super important for everybody because Buddhism is based on the tradition, that’s how it’s arrived to us – from word of mouth, through texts, through ancient texts.

But I think there’s many ways to introduce, make an introduction of Buddhism to the Western people who have no interest in religion, for example. Actually there are many people who have aversion towards religion. And I think, those are the people who are in the most need of getting in contact with the Dharma.

So that’s why I think it’s very important to create different ways to share and to explain Dharma to those people because they are the ones who need it the most; they are the ones who are suffering the most also.

So I agree with you that Dharma can be explained in many different ways, and today, I think, also there’s many different ways to explain it. Then slowly, slowly, there will be even more. So I think that’s very important.

Question: You said that if we are happy we inspire people to be happy. _ [missing] said that if we don’t do anything, we are not like too much – we are not happy. But if we are doing too many things, also we are not happy because we stress maybe of doing so many things. So what do you think to get a balance to find like happiness or we can an inspiration for people?

Lama Osel: Yeah, it’s important to listen to your body, right, because our body’s our vehicle – it’s what, where we live in since we were born ‘til we die, it’s where we live, we are alone inside.

The only way to communicate with people is through speech, through facial expression, through physical contact, maybe music, maybe painting, art, stuff like that. But ultimately, we are alone, right? So it’s so important to listen to our body because our body will tell us whether we are stressed or we have to take a slower pace.

I mean, sometimes, if we are not doing other exercise, then also our body will tell us by maybe some back pain. So it’s good to do like stretching exercises like yoga, something like that?

So it’s just, for each individual it’s different. So it’s just, I think the body will tell us when it’s the moment to stop working too much, and when it’s the moment to start doing something if we’re not doing a lot. But ultimately, of course, it’s the individual – each person has to see that by themselves.

So I think we have time for two more questions.

Question: What path is the one that you recommend for those people who have this kind of aversion towards religion? What way to go?

Lama Osel: Yeah, that’s a good question. I’m trying to also find out myself. But I think that, like the saying, “All roads lead to Rome”, and Rome is ourself. So I think it can be complicated in some moments, but I think eventually each person can find their own path.

Of course, it’s a very good question because not everybody finds it interesting or finds it helpful or useful. So maybe it’s just also a question of timing? When you reach a certain point in your life and you suddenly think, “Okay. Wow, I need to find meaning in my life. I have to understand what life is about”. And then maybe that thought [snaps fingers], will trigger the fact that you start searching for an answer or something. So sometimes it’s just the question about the moment in your life, and also your situation.

So it can be complicated but I think ultimately we were slowly able to reach more people, to be able to really find the true nature of their mind and understand how that works.

One more question.

Question: In your opinion, what is the best way to find an inner self, and not an outer self that is relying on your inner strength, and not something that it relies on outer things? And what’s like the path to find this?

Lama Osel: To find what?

Student: Like an inner sense that doesn’t rely on outer things….

Lama Osel: Oh, oh, okay.

Student:… to do with ego or attachment.

Lama Osel: Yeah, yeah. Well basically, wherever you are in the world, if you are not comfortable with yourself, whether you’re in Hawaii or you’re in Africa, it’s not going to make a difference. So you have to always start with yourself. And then how you relate to the outside world is based on how relate with yourself.

If you have many problems in your mind, then even if you go on vacation, then you will still have problems. So it’s important sometimes to also switch off the thoughts because many times we can be our worst enemy. At the same time, we can be our best enemy.

So it’s important to really check and see why we’re thinking, where it’s coming from and if it’s really helpful for us. ‘Cause, for example, one of the reasons there’s so much negativity in the world, from my perspective at least, is that people overvalue negativity much more than positive-ness.

Like, for example, there can be a mother who raised five children by herself for twenty years, and you’ll never see that on the news. You’ll never see, “Oh, this single mother raised five children by herself, doing two different jobs”.

But you will see a mother killed her son – that you may see. So that’s a good example to show that how even the news always overvalues negativity much more. And also we do because sometimes it’s like, it’s more interesting, oh we pay more attention. Oh there was an accident, and you say, “Wow, oh my God, there’s an accident”, which, of course, is terrible. But then there are so many other really nice things happening, and you say, “Okay, it’s normal”.

So if we can really switch that and overvalue positive-ness, and really say, “Okay, this person said this to me, which is very beautiful”, and really give a lot of importance to that, and slowly, slowly not give so much importance to the negative-ness, then that can really create a difference in our life and also in the people surrounding us.

And also in the collective memory because each individual affects the collective memory. So if we work with ourselves in that way, then we can actually help everybody else, even if it’s in a very subtle way.

I don’t know, I mean, I believe in the collective memory; maybe not all of you do. But I think the collective memory is a little bit like evolution or like god, or maybe sometimes love or karma – it can have many different names. It’s just sometimes you have to identify what works for you, what names, the one that you identify with.

For me, collective memory is like the omnipresence, like god. It’s something that we are all part of in an energetic way.

I don’t know, maybe I’m wrong. I don’t know. At least that’s what I believe now. It may change tomorrow.

So one last question.

Question: Hello. Since you left the monastery ten years ago, I’m just wondering how have been working to go through what you have to reach that stage. Have you been studying any other sects of Buddhism or other religions?]

Lama Osel: Well, since I left the monastery, which has been already almost ten years now, I’ve just been living life and suffering, and, and I’m going through what everybody else goes through. And I think one of the inspirations I’ve had apart from Buddhism is many different authors, like Alejandro Jodorowsky or Thich Nhat Hanh or Hermann Hesse and Eckhart Tolle, Paulo Coelho – just all these people. I just try to read books. Even Carlos Castaneda helped me a lot.

So since reading books and just experiencing life and talking with people, and just going through what everybody else goes through.

Of course, I had a raising in the monastery. So the way I saw things was a little bit different from people who grew up in the West. ‘Cause I grew up in the monastery with my basis as Dharma, and Buddhism, so it was easier for me to not get sucked into the samsara in a very deep way, so kind of just try to experience it and try to understand how it works.

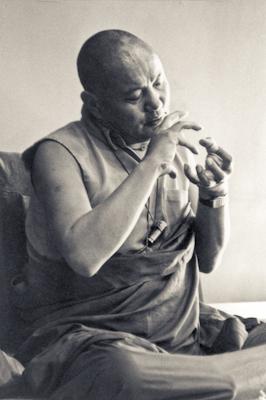

Yeah but of course, I think we are all sucked into it eventually, I mean, all the time. But that’s what’s so hard about it is to really find how to get out of it, and how to help people. And that’s what Venerable Gyatso is here for, is to help us find that way, that path.

So I just would like to thank Venerable Gyatso so much from the bottom of my heart for helping all of us. And maybe sometimes maybe hard to understand, but ultimately it’s so beneficial. It may be difficult to also not fall asleep sometimes. I’m joking. But at least try to sleep well at night, so that that doesn’t happen during the teachings because you can miss some very important stuff. ‘Cause it really is – lam-rim is the basis of Dharma. So if you get a good understanding of lam-rim, then you’ve got enough. With that, you have enough for the whole lifetime.

So that’s why this November course is very important, it’s historical for all of us. So just keep that in mind and try not to get stressed. And just keep a light-heart, light-mind, just try to [seems to be exhaling], don’t think too much. And if you think, think positive, right?

Okay, thank you so much. Thank you. [applause]

Now, supposedly all of you should be Dharma practitioners, including myself. But the question is to know what Dharma really is. Generally, the word Dharma has many meanings, many different connotations. We have philosophical explanations but we don't need to get involved in those. Practically, now, what we are involved in is practicing Dharma.

Now, supposedly all of you should be Dharma practitioners, including myself. But the question is to know what Dharma really is. Generally, the word Dharma has many meanings, many different connotations. We have philosophical explanations but we don't need to get involved in those. Practically, now, what we are involved in is practicing Dharma.

First Discourse: Dharma, Samsara, and Q&A

First Discourse: Dharma, Samsara, and Q&A

The Buddha said that many hundreds of Dharma traditions would come into this world. All traditions would arise from the perfect action of awakened buddhas and would be their means of helping sentient beings. What would these means be like? Entrusting ourselves to some religious traditions would enable us to take birth in the elevated planes of those religions: as human beings or as desire realm celestial beings. Through entrusting ourselves to others, we could be born into the seventeen planes of the form realm or in the four states of the formless realm. Moreover, they reveal ways of blocking the access to ill-gone states (as animals, etc.) and gaining elevated planes of existence. All give us strength and transforming powers.

The Buddha said that many hundreds of Dharma traditions would come into this world. All traditions would arise from the perfect action of awakened buddhas and would be their means of helping sentient beings. What would these means be like? Entrusting ourselves to some religious traditions would enable us to take birth in the elevated planes of those religions: as human beings or as desire realm celestial beings. Through entrusting ourselves to others, we could be born into the seventeen planes of the form realm or in the four states of the formless realm. Moreover, they reveal ways of blocking the access to ill-gone states (as animals, etc.) and gaining elevated planes of existence. All give us strength and transforming powers.