Concentration is important in both Dharma practice and ordinary life. The Tibetan word for the practice of concentration is shi-nä (zhi-gNas). Shi means peace and nä means to dwell; shi-nä, then, is dwelling in peace or being without busyness.

Concentration is important in both Dharma practice and ordinary life. The Tibetan word for the practice of concentration is shi-nä (zhi-gNas). Shi means peace and nä means to dwell; shi-nä, then, is dwelling in peace or being without busyness.

If we do not carefully watch the mind it may seem that it is peaceful. However, when we really look inside we see that this is not so. Mind does not rest on the same object for even a single second. It flutters around like a banner flapping in the wind. No sooner does mind settle on one object than it is carried away by another. Even if we live in a cave on a high mountain the mind moves incessantly. When we are on the top of a tall city building we can look down and see how busy the city is, but when we are walking on the streets we are aware of only a fraction of the busyness. Similarly, if we do not investigate correctly we will never be aware of how busy the mind really is.

Primary consciousness itself is pure and stainless, but gathered around it are fifty-one secondary mental elements, some of which are positive, some negative and some neutral. Of these secondary elements, in ordinary beings, the negative ones are stronger than the positive. Most people never attempt to gain control of these secondary mental elements; if they did they would be amazed at how difficult such a task is. Because the negative elements have dominated the mind for countless lifetimes, overcoming them will require tremendous effort. Yet shi-nä cannot be experienced until they have been totally subdued.

Primary consciousness itself is pure and stainless, but gathered around it are fifty-one secondary mental elements, some of which are positive, some negative and some neutral. Of these secondary elements, in ordinary beings, the negative ones are stronger than the positive. Most people never attempt to gain control of these secondary mental elements; if they did they would be amazed at how difficult such a task is. Because the negative elements have dominated the mind for countless lifetimes, overcoming them will require tremendous effort. Yet shi-nä cannot be experienced until they have been totally subdued.

Thus the busyness of the mind is mind-produced. This means that a mental rather than a physical effort is required to eliminate it. Nonetheless, when engaging in an intensive effort to develop shi-nä it is important to make use of certain secondary factors of a physical nature. For example, the place where one practises should be clean, quiet, close to nature and pleasing to the mind. And friends that visit should be peaceful and virtuous. One's body should be strong and free from disease.

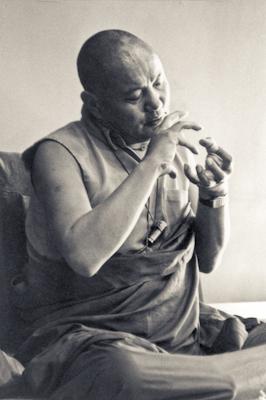

The practice of concentration requires sitting in a proper posture, to which there are seven points:

- Legs crossed and feet resting on the thighs, with soles turned upward. If this causes too much pain, it distracts from concentration. In which case, sit with the left foot tucked under the right thigh and the right foot resting on the left thigh.

- The trunk set as straight and erect as possible.

- Arms formed into a bow-shape, with elbows neither resting against the sides of the body nor protruding outward. The right hand rests in the left palm, with the thumbs touching lightly to form an oval.

- The neck straight but slightly hooked, with the chin drawn in.

- Eyes focused downward at the same angle as the line of the nose.

- Mouth and lips relaxed, neither drooping nor shut tightly.

- Tongue lightly held against the palate.

These are the seven points of the correct meditational posture. Each is symbolic of a different stage of the path. Also, there is a practical purpose in each of the seven:

- Having the feet crossed keeps the body in a locked position. One may eventually sit for a long period of time in meditation, even weeks or months in a single sitting. With legs locked, one will not fall over.

- Holding the trunk straight allows maximum functioning of the channels carrying the vital energies throughout the body. The mind rides on these energy currents, so keeping the channels working well is very important to successful meditation.

- The position of the arms also contributes to the flow of the energy currents.

- The position of the neck keeps open the energy channels going to the head and prevents the neck from developing cramps.

- If the eyes are cast at too high an angle the mind easily becomes agitated, if at too low an angle the mind quickly becomes drowsy.

- The mouth and lips are held like this to stabilize the breath. If the mouth is held too tightly shut, breathing is obstructed whenever the nose congests. If the mouth is help open too widely, breathing becomes too strong, increasing the fire element and raising the blood pressure.

- Holding tongue against the palate avoids an excessive build-up of saliva and keeps the throat from parching. Also, insects will not be able to enter the mouth or throat.

These are only the most obvious reasons for the seven points of the meditational posture. The secondary reasons are far too numerous to be dealt with here. It should be noted that the nature of the energy currents of some people does not permit them to use this position and they must be given an alternative. But this is very rare.

Although merely sitting in the vajra posture produces a good frame of mind, this is not enough. The main work, that done by the mind, has not yet even begun. The way to remove a thief who has entered a room is to go inside the house and throw him out, not to sit outside and shout at him. If we sit on top of a mountain and our mind constantly wanders down to the village below, little is achieved.

Concentration has two enemies, mental agitation, or busyness, and mental torpor, or numbness.

Generally, agitation arises from desire. An attractive object appears in the mind and the mind leaves the object of meditation to follow it.

Torpor arises from subtle apathy developing within the mind.

In order to have firm concentration these two obstacles must be eliminated. A man needs a candle in order to see a painting which is on the wall of a dark room. If there is a draught of wind the candle will flicker too much for the man to be able to see properly and if the candle is too small its flame will be too weak. When the flame of the mind is not obstructed by the wind of mental agitation and not weakened by the smallness of torpor it can concentrate properly upon the picture of the meditation object.

In the early stages of the practice of concentration mental agitation is more of a hindrance than torpor. The mind is continually flying away from the object of concentration. This can be seen by trying to keep the mind fixed on the memory of a face. The image of the face is soon replaced by something else.

Halting this process is difficult, for we have built the habit of succumbing to it over a long period of time and are not accustomed to concentration. To take up the new and leave behind the old is always hard. Yet, because concentration is fundamental to all forms of higher meditation and to all higher mental activity, one should make the effort.

Mental agitation is overcome principally by the force of mindfulness and torpor by attentive application. In the diagram representing the development of shi-nä there is an elephant. The elephant symbolizes the meditator's mind. Once an elephant is tamed, he never refuses to obey his master and he becomes capable of many kinds of work. The same applies to the mind. Furthermore, a wild and untamed elephant is dangerous, often causing terrible destruction. Just so, the untamed mind can cause any of the sufferings of the six realms.

At the bottom of the diagram depicting the development of concentration the elephant is totally black. This is because at the primary stage of the development of shi-nä mental torpor pervades the mind.

In front of the elephant is a monkey representing mental agitation. A monkey cannot keep still for a moment but is always chattering and fiddling with something, being attracted to everything.

The monkey is leading the elephant. At this stage of practice mental agitation leads the mind everywhere.

Behind the elephant trails the meditator, who is trying to gain control of the mind. In one hand he holds a rope, symbolic of mindfulness, and in the other he holds a hook, symbolic of alertness.

At this level the meditator has no control whatsoever over his mind. The elephant follows the monkey without paying the slightest attention to the meditator. In the second stage the meditator has almost caught up with the elephant.

In the third stage the meditator throws the rope over the elephant's neck. The elephant looks back, symbolizing that here the mind can be somewhat restrained by the power of mindfulness. At this stage a rabbit appears on the elephant's back. This is the rabbit of subtle mental torpor, which previously was too fine to be recognized but which now is obvious to the meditator.

In these early stages we have to apply the force of mindfulness more than the force of mental attentive application for agitation must be eliminated before torpor can be dealt with.

In the fourth stage the elephant is far more obedient. Only rarely does he have to be given the rope of mindfulness.

In the fifth stage the monkey follows behind the elephant, who submissively follows the rope and hook of the meditator. Mental agitation no longer heavily disturbs the mind.

In the sixth stage the elephant and monkey both follow meekly behind the meditator. The meditator no longer needs even to look back at them. He no longer has to focus his attention in order to control the mind. The rabbit has now disappeared.

In the seventh stage the elephant is left to follow of its own accord. The meditator does not have to give it either the rope of mindfulness or the hook of attentive application. The monkey of agitation has completely left the scene. Agitation and torpor never again occur in gross forms and even subtly only occasionally.

In the eighth stage the elephant has turned completely white. He follows behind the man for the mind is now fully obedient. Nonetheless, some energy is still required in order to sustain concentration.

In the ninth stage the meditator sits in meditation and the elephant sleeps at his feet. The mind can now indulge in effortless concentration for long periods of time, even days, weeks or months.

These are the nine stages of the development of shi-nä. The tenth stage is the attainment of real shi-nä represented by the meditator calmly riding on the elephant's back.

Beyond this is an eleventh stage, in which the meditator is depicted as riding on the elephant, who is now walking in a different direction. The meditator holds a flaming sword. He has now entered into a new kind of meditation called vipasyana, or higher insight: (Tibetan: Lhag-mthong). This meditation is symbolized by his flaming sword, the sharp and penetrative implement that cuts through to realization of Voidness.

At various points in the diagram there is a fire. This fire represents the effort necessary to the practice of shi-nä. Each time the fire appears it is smaller than the previous time. Eventually it disappears. At each successive stage of development less energy is needed to sustain concentration and eventually no effort is required. The fire reappears at the eleventh stage, where the meditator has taken up meditation on voidness.

Also on the diagram are the images of food, cloth, musical instruments, perfume and a mirror. They symbolize the five sources of mental agitation, i.e. the five sensual objects: those of taste, touch, sound, smell and sight, respectively.

Most people take the mental image of a Buddha-form their object of concentration in order to develop shi-nä. First one must become thoroughly familiar with the object that one will focus on. This is done by sitting in front of a statue or drawing of the object for a few sessions and gazing at it. Then try sitting in meditation, holding the image of the form in mind without the aid of the statue or drawing. At first your visualization of it will not be very clear nor will you be able to hold if for more than a few seconds. Nonetheless, try to hold the image as clearly and for as long a period as possible. By persisting you will soon be able to retain the image for a minute, then two minutes and so forth. Each time the mind leaves the object apply mindfulness and bring it back. Meanwhile, continually maintain attentive application to see if unnoticed disturbances are arising.

Just as a man carrying a bowl full of water down a rough road has to keep one part of his mind on the water and another part on the road, in shi-nä practice one part of the mind must apply mindfulness to maintain steady concentration and another part must use attentive application to guard against disturbances. Later, when mental agitation has somewhat subsided, mindfulness will not have to be used very often. However, then the mind is fatigued from having fought agitation for so long and consequently torpor sets in.

Eventually, a stage comes when the meditator feels tremendous bliss and peace. This is actually only extremely subtle torpor but it is often mistakenly taken to be real shi-nä. With persistence, this too disappears. The mind gradually becomes more clear and fresh and the length of each meditation session correspondingly increases. At this point the body can be sustained entirely by the mind. One no longer craves food or drink. The meditator can now meditate for months without a break. Eventually he attains the ninth stage of shi-nä, at which level, the scriptures say, the meditator is not disturbed even if a wall collapses beside him. He continues to practice and feels a mental and physical pleasure totally beyond description, depicted in the diagram by a man flying. Here his body is inexhaustible and amazingly supple. His mind, deeply peaceful, can be turned to any object of meditation, just as a thin copper wire can be turned in any direction without breaking. The tenth stage of shi-nä—or actual shi-nä, is attained. When he meditates it is as though the mind and the object of meditation become one.

Now the meditator can look deeply into the nature of his object of meditation while holding all details of the object in his mind. This gives him extraordinary joy.

Here, looking into the nature of his object of meditation means that he examines it to see whether or not it is pure, whether or not it is permanent, what is its highest truth, etc. This is the meditation known as vipasyana, or higher insight. Through it the mind gains a deeper perception of the object than it could through concentration alone.

Merely having shi-nä gives tremendous spiritual satisfaction; but not going on to better things is like having built an aeroplane and then never flying it. Once concentration has been attained, the mind should he applied to higher practices. On the one hand it has to be used to overcome karma and mental distortion, and on the other hand to cultivate the qualities of a Buddha. In order to ultimately accomplish these goals, the object of meditation that it takes up must be voidness itself. Other forms of meditation are only to prepare the mind for approaching voidness. If you have a torch with the capacity to illuminate anything you should use it to find something important. The torch of shi-nä should be directed at realization of voidness for it is only a direct experience of voidness which pulls out the root of all suffering.

In the eleventh stage on the diagram two black lines flow out of the meditator's heart. One of these represents klesavarana, the obscurations of karma and mental distortion. The other represents jneyavarana, the obscurations of the instincts of mental distortion. The meditator holds the wisdom-sword of vipasyana meditation, with which he plans to sever these two lines.

Once a practitioner has come close to understanding voidness he is on his way to the perfection of wisdom. Prajna-paramita, the ultimate goal of the development of concentration.