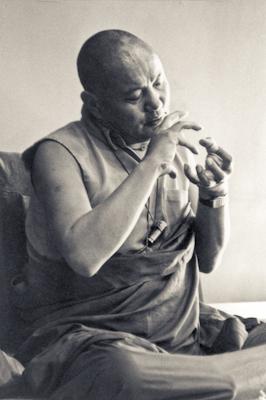

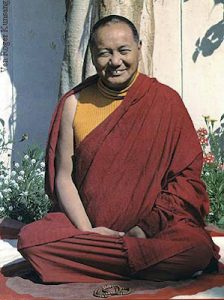

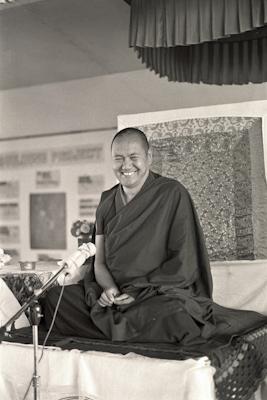

| A teaching on karma given by Lama Yeshe at Chenrezig Institute, Queensland, Australia, on 28 June 1976. Edited by Dr. Nicholas Ribush.

Excerpts from this teaching have been published in Mandala magazine, issues February 2004 and April 2004. |

Beginning to Understand Karma

Beginning to Understand Karma

There’s not just one, fixed, mathematical way of explaining karma; there are many different ways, including the subheading and numbered list approach. Sometimes it seems that people new to Buddhism find karma hard to understand, but actually, it’s easy to get a rough, initial understanding of it.

Of course, once you get into the details, karma can be extraordinarily complex, too, but when I introduce it to beginners, I try to keep it simple so that they can get at least a basic, intellectual understanding. In reality, the only way you can get a total understanding of karma is through your own experience, and that experience is beyond words.

Trying to get a total understanding of karma through the intellect alone is like trying to count every atom of earth, water, fire and air in the universe, which is impossible,

Fundamentally, what is karma? Karma is your body, speech and mind. That’s it. It’s very simple. If I were to try to compare the subject of karma to the kinds of thing you study in the West, I’d say that it parallels in some ways the theory of the evolution of everything that exists. Karma encompasses everything on Earth and beyond, every existent phenomenon in the universe, throughout infinite space—in Buddhist terms, every phenomenon in samsara and nirvana. Karma is the energy of all phenomena and has nothing to do with what your mind believes.

If karma encompasses all relative phenomena, are these phenomena interconnected? Well, even modern science understands that all the energy in the universe is interdependently related; it’s not just Buddhist dogma.

For example, where does all the green vegetation we see around us come from? It doesn’t arise without cause. First there has to be a cause; then, the effect—the relative appearance of the green—arises. Similarly, each of us also has a cause; we, too, are interdependent phenomena. We depend on other energies for our existence. Those energies, in turn, depend on yet other energies. In this way, all energy is linked.

You probably think your body comes from the supermarket: as long as the supermarket’s there, you can eat; as long as you can eat, you exist. Obviously, it goes much deeper than that. Therefore, your conception of what you are—“I am. I’m this; I’m that; I’m this—is like a dream. Intuitively, your ego has this notion that you’re independent, that you’re not a dependent phenomenon. That’s complete rubbish.

If you look, you can easily see how you’re interdependent. It looks complicated; it’s not complicated. It only becomes complicated if your mind thinks it’s complicated. Your mind makes things up; that’s karma, too—an interdependent phenomenon; it exists in relation to other energy. If you understand the basic simplicity of this, you’ll be more careful in the way you act because you’ll realize that every single action of your body, speech and mind produces a reaction.

We describe samsara as cyclic: it’s like a wheel, it goes round; one thing produces another, that produces another, and so it goes on, one thing pushing the other. And each karmic action is like the seed that produces a flower that in turn produces hundreds of seeds, which then result in hundreds more flowers that produce hundreds more seeds each. In this way, in a relatively short time, one seed produces thousands and thousands of results.

The actions of your body, speech and mind are the same. Each action, positive or negative, good or bad, produces an appropriate result.

Also, karma doesn’t depend on your believing in it or not. The mere fact of your existence proves the existence of karma. Irrespective of whether you want to know about karma or not, whether you believe in it or not, it doesn’t matter: you are karma. Whether you accept karma or reject it, you can’t separate yourself from karma any more than you can separate yourself from energy. You are energy; you are karma. If you’re a human being, it doesn’t matter whether others think you’re a human being or not—you’re a human being. It doesn’t depend on what you think, either. The truth of all existence doesn’t depend on what people believe.

Sometimes you might think, “OK, Buddhists accept karma. They try to do good, avoid evil and perhaps enjoy positive results, but what about people who don’t believe in karma?”

But whether you believe or not, your suffering and problems have a cause. They don’t depend on what you believe. Do you think you suffer only because you think you suffer? No. Even if you say, “I’m not suffering,” you’re suffering. Suffering comes along with your very life.

Therefore, I often say that the Buddhist connotation of religion is a little different from the Western one. But when I say that, I’m not saying Buddhism is better; it’s just different. Its analytical approach is different.

Understanding Karma

When we teach karma, we often refer to its four characteristics, the first of which is that karma is definite.

Karma means action, your energy, and karma’s being definite means that once you have set in motion a powerful train of energy, it will continue running until it either is interrupted or reaches its conclusion. Karma’s being definite does not mean that once you have created a specific karma there’s nothing you can do to stop it. That’s a wrong view of karma.

Take, for example, the attitude of certain followers of the Hindu religion. You’ll find many people like this in India and Nepal: they believe in karma, but they believe it’s completely fixed. “I was born a carpenter. God gave me this life. I’ll always be a carpenter.” “My karma made me a cobbler; I’ll always be a cobbler.” They are very sincere in their belief, but very wrong in thinking that karma can’t be changed. When Westerners come across such people they can’t believe that they can think this way. Westerners know immediately from their own experience that if you really want to change your status in life you can do so.

But because these people’s misconceptions are so strong, they can’t change. It’s silly, isn’t it? That kind of super-belief is religious fanaticism. It’s ignorant; it closes your mind and prevents you from expanding and developing it.

I also sometimes see great misconceptions about karma in new Dharma students. They read and think about karma, accept its existence, but then become too sensitive about it. If they make a mistake in their actions, they get emotionally terrified and guilty. That’s wrong, too.

The karmic energy of your body, speech and mind comes from your consciousness. Some scientists say that there’s a totality of energy from which all other energy manifests. Be that as it may, in the same way, all of the energy of your body, speech and mind comes from your consciousness, your mind—from your mind; your consciousness.

If you put your energy into a certain environment and a certain channel, a different form of energy will manifest. It changes. If you direct your conscious energy one way, one kind of result will come; if you direct it another way, a different kind of result arises. It’s very simple. But what you have to know is from what source your actions come. Once you do, you’ll see that you are responsible for what you do; you can determine what you do and what happens to you. It’s more up to you than to your circumstances, friends, society or anything else outside you.

If, however, you don’t know that it’s possible to direct the energy of your body, speech and mind or how to do it, if you have no idea of how cause and effect operates in everyday life, then of course, you have no chance of putting your energy into positive channels instead of negative ones. It’s impossible because you don’t know.

Positive actions are those that bring positive reactions; negative actions are those that bring negative reactions, restlessness and confusion. Actions are termed positive or negative according to the nature of their effects.

In general, it’s our motivation that determines whether our actions are positive or negative; our mental attitude. Some actions start out negative but can become positive due to the arising of an opposing kind of energy. The Abhidharma philosophical teachings talk about absolute positives, such as the true cessation of suffering, but for us, it’s more important to understand positive and negative on the relative level. That’s what we’re dealing with in our everyday lives: relative positives and relative negatives.

However, we’re usually unconscious whenever we act. For example, when we hurt our loved ones, it’s mostly not deliberate but because we’re unconscious in our actions. If we were aware that every action of our body, speech and mind constantly reacts internally within us and externally with others, we’d be more sensitive and gentle in what we did, said and thought.

Sometimes our actions are not at all gentle but like those of a wild animal. Next time you’re acting like a wild animal, check up which channel your energy’s in at that time and understand that you can change it—you have the power, the wisdom and the potential to do so. You can redirect your energy from the negative into the positive channel.

Also, you have to accept that you’re going to make mistakes. Mistakes are possible. You’re not Buddha. When you do make an error, instead of freaking out, acknowledge it. Be happy: “Oh, I made a mistake. It’s good that I noticed.” Once you’ve recognized a mistake, you can investigate it intensively: what’s its background? What caused it? Mistakes don’t just pop up without reason. Check in which channel your mind was running when that mistake happened. When you discover this, you can change your attitude.

In particular, you have to understand that negative actions come from you, so it’s up to you to do something to prevent their negative reactions from manifesting. It’s your responsibility to act and not sit back, waiting for the inevitable suffering result to arise.

Therefore, instead of simply accepting what happens to you, believing “This is my karma” and never trying to work with and change your energy for the better, understand that you can control what happens to you and be as aware of your actions as you possibly can.

Karma, inner strength and life itself

To over-simplify, according to even normal society’s way of thinking, anything you do dedicated to the benefit of others is automatically positive, whereas anything you do just for your own benefit automatically brings a negative reaction. Whenever you act selfishly, your heart feels tight, but when you try to really help others, psychologically you experience openness and a release that brings calm and understanding into your mind. That is positive; that is good karma.

However, if you don’t actively check your motivation, you might think or say the words, “I’m working for the benefit of others,” but actually be doing the opposite. For example, some rich people give money with the idea that they’re helping others but what they really want to do is to enhance their own reputation. Such giving is not sincere and has nothing whatsoever to do with positive action or morality.

Giving with the expectation that others will admire you is giving for your own pleasure. The end result is that it makes you berserk, restless and confused. Check up. Look at the way normal people act; it’s so simple. Even if you give away huge amounts of money, if you do it with selfish motivation, expecting tremendous results for yourself, you end up with nothingness. It’s a psychological thing; there’s more to giving than just the physical action.

Take me, for example. I can sit cross-legged in the meditation posture and you’re going to think, “Oh, Lama’s meditating.” But if my mind is off on some incredible trip, although it looks as if I’m doing something positive, in fact I’m doing something completely neurotic and confused. You can never judge an action from its external appearance; its psychological component is much more important.

Therefore, be careful. In particular, acting out of loving kindness doesn’t always mean smiling, hugging and telling people, “Oh, I love you so much.” Of course, if that’s what somebody needs, then go ahead and stroke or hug that person; I’m not saying that you have to give up all physical contact. You just have to know what’s appropriate at any given time.

I have seen many students come to a meditation course, learn about love, compassion and bodhicitta for the first time, and at the end of the course be all fired up, wanting to help others: “Lama, I want to go to Calcutta and serve the sentient beings suffering there.”

I say, “You want to go? OK, go and try to help as best you can.” So they go, full of emotion, and, of course, see terrible suffering; poverty, starvation, disease and so forth. After a month, they have to leave, exhausted, because they find that simply going there, trying to help, isn’t really the solution.

A couple of my students, beautiful young women, went to Pakistan and Calcutta, hoping to express their loving kindness through serving where suffering was greatest. I told them to go, and return when the time was right. When they got there they discovered that what they were doing wasn’t really helping, and it wasn’t long before they were back.

Actually, expressing loving kindness through action is quite difficult. You have to be very skillful. It takes great wisdom. If you set out on a mission with no understanding, just a tight, emotional feeling of wanting to help, you’re in danger of losing yourself. For example, if you see somebody drowning and emotionally jump in without being able to swim, all that happens is that you both lose your lives.

Our physical energy is limited. Therefore, we’re limited in helping others in this way—we try to help others physically but come up empty; it’s beyond us. If you do want to help others out of loving kindness, act according to your ability and know your limits. Don’t overburden yourself because of emotion and incomplete understanding.

Mental energy, however, is practically unlimited. If we realize loving kindness, we’re like a ship. No matter how heavy the load, a ship can bear it. Similarly, with true loving kindness we can handle any situation that arises without freaking out. Furthermore, a ship does not discriminate; it carries whatever it’s given. Similarly, with loving kindness, we won’t favor one person over another: “You—come in; you—go away.”

When we practice Dharma and meditation, we build the inner strength necessary to be of greatest benefit to others and are able to face any difficulty that arises. Practitioners who are afraid to hear about suffering aren’t facing reality. The maha in Mahayana Buddhism means “great.” A Mahayana practitioner is supposed to be capacious and, like a ship, be able to take whatever comes along.

If we’re small-minded and hypersensitive, even tiny atoms can cause us to recoil: “I don’t want that atom.” That’s not the way of the Dharma practitioner.

Even the average, simple person who wants his or her life to be successful should be able to face whatever situation arises. If you freak out at the smallest thing, you’ll never make even this life successful. Everyday life is completely unpredictable; you can’t fix things to work out in a certain way. As things change, you have to change with them. You have to be flexible enough to deal with whatever happens.

If this is true for the ordinary person, how much more true must it be for the Dharma practitioner? You have to have the courage to face any difficulty that you encounter: “I can overcome any obstacle and reach perfect liberation.” Crossing the ocean of samsara is not easy, but it’s not samsara that’s difficult—it’s your own mind. What you actually have to cross is the ocean of your schizophrenic mind and you need to be confident that you can deal with that.

First you have to be able to think, “I can face whatever comes without running from it.” Life is not easy; forget about meditation—life itself is hard. Things change; the mind changes. You have to face each change as it comes.

Going into retreat doesn’t mean that you’re running away from society and life because you’re afraid of them. However, you need to develop confidence that you’ll be able to handle anything that life throws at you. What you really need to judge, though, is what the most advantageous thing to do at any particular time is: to stay in society or go into retreat. Whatever you undertake is in your own hands; what you need to know is why you are doing it.

Karma, Reality and Belief

We often talk about how we waste our lives following the eight worldly dharmas—attachment to temporal happiness, receiving material things, being praised and having a good reputation and aversion to their opposites: discomfort, not getting things, being criticized and notoriety. Each time we get involved with those, we create negative karma.

For example, when somebody praises you, you feel happy and puff up with pride, and when somebody criticizes you, you feel unhappy and depressed. Each time you go up and down like this, you create karma.

Why do you feel elated when praised and dejected when criticized? It’s because you don’t accept the way things truly are. You’re controlled by your hallucinating mind, which is totally divorced from reality. Whether you’re good or bad isn’t determined by what other people think but by your own actions. These are your own responsibility. If all your actions are positive, even if I say “You’re bad, you’re bad, you’re bad…” all day, it won’t affect your qualities. Therefore, you should understand what really makes an action positive or negative. It’s not defined by what other people think.

This is scientific fact, not religious dogma. If you go up and down because of what other people say, you’re hallucinating; you’re not seeing reality. You should have strong confidence in your own actions and take full responsibility for them. Then, even if all sentient beings turn against you, you’ll still be laughing. When you know what you are, you never get upset. If, on the other hand, your body and mind are weak, if you have no self-confidence and feel insecure, then of course you’re going to experience problems.

All your feelings, perceptions, discriminations and the rest, especially those mental factors that bring negative reactions, arise from the hallucinating mind. Therefore, quite early in their training, I teach my students to meditate on the nature of feeling.

We always think that whatever we feel—physically or mentally—must be right. Similarly, we think that whatever we see is real; we really do believe in what we see. I’m not talking about spiritual belief in the supernatural; I’m saying that we believe in the concrete reality of what we see around us every day. Do you think that’s right or wrong? It’s wrong.

For example, say that you’re tremendously attracted to a particular object. At that time you have a certain fixed idea of what that object is. But you’re fantasizing; it’s a hallucinated fantasy. If you check your mind of attraction closely, you’ll see that its view is totally polluted and that what you perceive is a fantasy—neither the reality of the object nor that of the subject. A kind of cloud has appeared between your mind and the object and that’s what you see. All delusions arise in that way.

So, in the end, who has more beliefs—a religious person or an atheist? It’s the atheist. Atheists are prone to say, “I don’t believe anything,” but that’s just their ego speaking. They believe what they see; they believe what they feel; they believe what they think. For example, atheists consider certain things beautiful—that’s belief. This is the scientific truth of the situation. It doesn’t matter whether or not they use the word “belief”—they believe; they’re completely captivated by belief.

I can make the definitive statement that if your mind is clouded by the dark shadow of ignorance, if attachment rather than free communication is driving your personal involvements, you’re a believer. This is simple and logical. That’s why I always say that Dharma is very simple. It reveals the reality of yourself, your life and the things around you…the reality of everything. That’s the meaning of Dharma.

When some people go into a supermarket, they see the incredible display of goods as a reflection in a mirror. It’s like when you look into a mirror, you see your reflection but at the same time you know it’s not really you. That’s how those whose view of the nature of the supermarket is closer to reality see it—like a reflection. Therefore, they can control any attachment that’s likely to arise. Those whose view of the world is that of a more concrete reality see the goods in a supermarket as fantastic and can’t stop their senses from vibrating.

That’s the nature of ordinary attraction. Objects to which you’re attached make you tremble with desire and things that you hate make you shake with anger. Either way, it’s because you don’t understand reality.

Actually, those who really understand the absolute nature of the supermarket don’t see anything at all. The whole thing disappears. That might be too much for you to comprehend, but there’s truth in what I’m saying.

In conclusion, then, no matter how negative the things you’ve done, if you have powerful understanding, you can purify them completely. There’s no such concrete negative action that can never be purified; there’s a solution for everything.

Some Christians speak of certain concrete sins that send you to a permanent, everlasting hell. I’m not criticizing; it’s a philosophical point of view. It’s good; it has a purpose. Any philosophy with a purpose is always good. But you should never think, “I have created such horrible negative actions that I’ll never be able to overcome them.” That’s an incredible devaluation of your human nature. Any kind of negativity, no matter how great, can be purified. That’s the power of the human mind.

That’s why the lam-rim starts out by teaching how great our human potential is. We have to understand the true value of our life. We always seek value externally. People even lose their lives in pursuit of material things or recreational pleasure. What a ridiculous waste of life!

Check within yourself very skillfully to see if you value material things more than your internal potential. That will show you how much you understand.

Now, supposedly all of you should be Dharma practitioners, including myself. But the question is to know what Dharma really is. Generally, the word Dharma has many meanings, many different connotations. We have philosophical explanations but we don't need to get involved in those. Practically, now, what we are involved in is practicing Dharma.

Now, supposedly all of you should be Dharma practitioners, including myself. But the question is to know what Dharma really is. Generally, the word Dharma has many meanings, many different connotations. We have philosophical explanations but we don't need to get involved in those. Practically, now, what we are involved in is practicing Dharma.