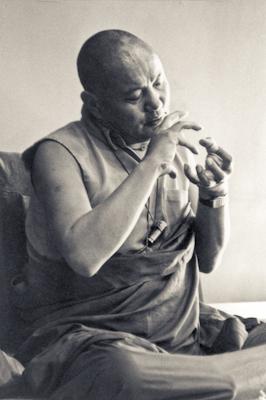

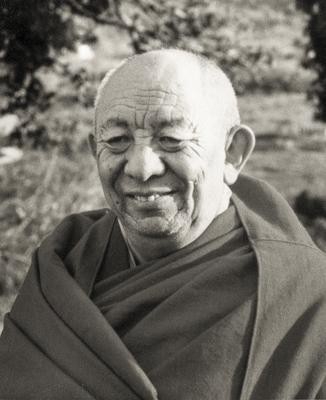

| A teaching on The Three Principal Aspects of the Path by Ven. Denma Lochö Rinpoche at Jamyang Buddhist Centre, London, in early October 2001.The Three Principal Aspects of the Path is a text by Lama Tsongkhapa (1357-1419) which covers the entire Buddhist path to enlightenment. |

CHAPTERS

Part 1: Renunciation

Part 2: Renunciation

Part 3: Bodhicitta

Part 4: Correct View of Emptiness

Part 2: Renunciation

So to begin the teaching, let us correct our attitude, and contemplate - as far as space extends are existing countless sentient beings in a state of dissatisfaction or suffering. In order to separate or liberate each and every one of those sentient beings, I myself must achieve the highest unsurpassable enlightenment and in order to do that I am now going to receive the commentary on the unmistaken path in the form of The Three Principles of the Path.

The Benefits of Hearing the Teaching

So again to reflect upon the benefits of listening to the teaching - if we use a quotation from a text called 'Wisdom', then the first line of this reads that 'listening is the lamp which dispels the darkness of ignorance'. So here the example is quite clear - in a worldly sense, if we walk into a dark room holding an oil lamp, or if we just turn the light on, through having light in that room we are able to see what previously we couldn't see because the room was dark. So in the same way, if we think about the things which are to be taken up, the things which are to be abandoned, or the karmic law of cause and effect, or the view of suchness (that is to say the correct view of reality) as the objects to be seen in a room, then the light which will dispel the darkness of ignorance with regard to those particular objects which are to be seen in the room is the hearing of the teaching. So through hearing then we are able to dispel ignorance about what objects are to be known (for example, the karmic law of cause and effect), and what is to be taken up and what is to be abandoned with regard to our behaviour. Then when we reflect upon this practice of hearing, it's not just hearing the teaching; the way we make the lamp blaze forth is through hearing the teaching and then contemplating the meaning of that and then meditating upon that in a single-pointed fashion. For example if we take thusness, then through initially hearing the teaching on that, contemplating the meaning of that and then single-pointedly meditating upon that, we are able to achieve liberation from the cycle of existence. Again then the root of this liberation is hearing the teaching. It is like wanting to do something within a room and then carrying in an oil lamp to then be able to see what forms, what objects, are in that room and then getting to grips with those objects, or working with those objects. So hearing the teaching initially then is something very important as it is like the lamp which dispels the ignorance with regard what is to be taken up and what is to be abandoned ie the karmic law which for us as practitioners is something that is extremely important and something that we should become very familiar with; and then with regard to suchness, or the ultimate mode of phenomena, if we don't understand this correctly then there is no liberation. So if we talk about two kinds of darkness, or two kinds of ignorance, both of which because their nature is darkness, are removed by the lamp of hearing the teaching. So then the 'hearing is the lamp which dispels the darkness of ignorance'.

The second line of the stanza from the text 'Wisdom' reads 'hearing is like the weapon which destroys the enemy of the destructive emotions'. So here then if we think in ancient India what was meant by weapons, it was like throwing-stars, daggers, swords and so forth. However in these modern times there are various other kinds of weapons but whatever the weapon is, it is an object which is used to destroy something else. In this case, the weapon of listening is used to destroy the enemy of the destructive emotions. For example, if we are a person who has a lot of anger, through meditating on its antidote, love, we are able to overcome that enemy of anger and thoroughly destroy it so it is no longer any burden upon our being. In the same way, if we are a person who has a lot of attachment, either for our own physical form or for another's physical form or for some other object like a precious jewel, then we can reverse that attachment by thinking about the repulsiveness of that particular object. Through this meditation we can lessen and then thoroughly remove and destroy this enemy of the destructive emotions which one has in one's mental continuum, or mind. Initially then one must come to recognise what is actually meant by an enemy, what an enemy is, then after having that recognition we must apply the antidote or the weapon. The weapon here which we are going to apply is something that we can only have gained through engaging in the practice of hearing the teaching. So thus in the second line, the actual thing which destroys the enemy of the destructive emotions is like a weapon, and this weapon is brought about, or manufactured, through hearing the teaching. So hearing then is like a 'weapon which destroys the enemy of the destructive emotions'.

The third line says that 'hearing the teaching is the best of all possessions'. What we usually mean by possessions are various things which we might have in our house and which cause us a great amount of anxiety, or worry. That is to say, the more possessions we seem to gain, they just seem to add to our burden of anxiety, that is to say, we worry that they might be carried away by thieves, or we worry about fire in the house, or these days, flooding in the house, destroying the wealth or possessions which we have striven so hard to gain. So in the same way, when we think about the possession of hearing the teaching and the wisdom which arises through that - if we have that in our mindstream it is not something which can be destroyed by the four elements - water, fire and so forth; it is not something that can be carried off by thieves and bandits; it is rather something that is continually with us and which there is no danger of losing. So the third line of this stanza from the text 'Wisdom' instructs us that wisdom is the best of all possessions for those very reasons.

So the last line of this stanza then describes hearing as 'the best of associates or friends'. So we can understand this from our own experience - when fortune is with us then we seem to have a lot of friends or associates around us. However when circumstances change for the worse, we do seem to find that these close, or seemingly close, friends or associates seem to go farther and farther away from us, abandoning us in our time or hour of need. With regard then to the practice of hearing and the knowledge we have gained through that, then in difficult situations or in positive situations, that friend continually remains with us in all circumstances. In a worldly sense then when circumstances are good, we seem to have a lot of friends and then when circumstances are bad, our friends seem to keep a distance and then finally disappear from sight. So actually if we compare ourselves - a person who has heard the Dharma teaching and has contemplated the Dharma teaching and has that kind of friend, with somebody who doesn't have that kind of friend, then during the good times there is not really that much difference between us. However in the difficult times when circumstances change for the worse, we find that through contacting this friend, that is to say bringing to mind the teachings we have heard - like if we lose wealth for example, we can contemplate on the changing nature of the cycle of existence; if we have various sicknesses or illnesses befall us or bereavements and so forth, we can again contemplate on the suffering nature of the cycle of existence; if we are harmed by other human beings or perhaps various snake spirits and so forth - whatever the harmer - we can reflect upon how we might have harmed that particular individual in a previous existence, thus we can contemplate on the karmic law; we can also then expand our view to include others, thinking that this is just a small difficulty when compared with the difficulties of all other sentient beings which are around me and in the world system. Thus we can utilise this friend, we can chat with this friend which is the friend of initially hearing the teaching - this excellent associate which doesn’t abandon us during our hour of need but is continually there for us. Thus hearing the teaching and the knowledge gained therefrom is like the 'best of friends or associates'.

Contemplation on Suffering

So now we come to the text which we are going through. Initially then let us contemplate on dissatisfaction or suffering; the reason for this is that we have to know what suffering is in order to turn away from dissatisfaction or suffering. Through trying to achieve liberation we need to remove this grasping attachment so we have to understand the faults of what we are attached to, and then through understanding those faults, we can turn away from them. At present our mind is infatuated and continually holding on to, or stuck to, the cycle of existence. Through thinking of the faults then of the cycle of existence, we can turn our minds away from the cycle of existence, or the cycle of pain. So this is mentioned by Lama Tsongkhapa in his writings when he says that the more we are able to contemplate on the faults of the cycle of existence, or dissatisfaction, then the stronger our yearning for liberation will become. So this we can see from an example: If we are a prisoner in a prison and we just sit in our room thinking 'well, they give us food, there's good lighting here, I think I'll just stay here' - then for that individual there is no hope, there is no way that that person is going to even take a step outside of his or her prison cell. So in the same way, if an individual is in a prison cell and he or she thinks 'I must get out of this predicament' - through thinking about the benefits of being released from jail - thinking about being able to work in various places, being able to travel to various countries, being able to enjoy various kinds of scenes and enjoyments and so forth; and then thinking about how bound one is in the prison cell - thinking that 'I can't move, I have no freedom to do what I want, I have no enjoyment through staying here' - through thinking thus, the faults of staying in the prison and the benefits of leaving the prison kind of naturally increase. So like this, if we think about the faults of the cycle of existence, the difficulties therein, our yearning for liberation from this cycle of existence will increase naturally; and the stronger our yearning for freedom from the cycle of existence, the stronger our Dharma practice and so our practice of turning away from the cycle of existence, or renunciation (the first of these three points) will become.

The Four Noble Truths

So this reflection on dissatisfaction or suffering cannot be over-emphasised. For example (I forgot to translate from before), when the Buddha first taught the Four Noble Truths in Varanasi, at that time, the first thing he said to his five disciples was 'this is the truth of dissatisfaction' (or 'this is the truth of suffering'). So the reason for saying that initially was to get his disciples to recognise the truth of suffering, or the fact that everything within contaminated existence, that is to say, within the cycle of existence is in and of itself or by its own nature -

[end of side - tape breaks here] …existence and our experience, and through that, through contemplating the Four Noble Truths we can turn away from the cycle of existence. So this is why the teaching of the Four Noble Truths was given initially - in order to jar the disciples into recognising the dissatisfaction inherent in the cycle of existence. So if we then have a quick look at the Four Noble Truths (that is the truth of suffering, the cause of suffering, the cessation and then the path leading to the cessation); if we emphasise or go a little bit vaster in our explanation of the first truth, that is to say, the truth of suffering, then we will just whizz through the latter three. Through the understanding of the first, this will imply the understanding of the latter three - this can be seen in an example from the text known as 'The Uttaratantra of Maitreya'. In this text it says that the truth of suffering is like the crop, and the cause of suffering is like the seed of that crop, then the cessation is the non-existence of that crop and the path leading to that cessation is the fire which burns the seed which renders it barren and unable to produce its crop. So that is very clear, isn’t it - if we have a crop which we do not want, we need to uproot or prevent the seed of that crop from producing its fruit or its crop, so the way to do that is to make the seed barren and through that it cannot produce or give rise to its fruition, that is to say, the crop. So in the same way then, through recognising the lot, or the 'crop' of dissatisfaction which we have, we can set about burning or removing the causes for that, and the way to do that is through contemplating the cause which will eliminate that result, that is to say, the truth of dissatisfaction, and naturally bring about the truth of cessation.

Three Kinds of Suffering

So with regard to the first noble truth, that is the truth of dissatisfaction, or suffering, with this there are various ways we can divide it - a division into three is presented, four, six, seven and so forth. However as we are only giving an abbreviated commentary, let us just dwell upon the division of suffering into three. Through dwelling upon these three and contemplating them in relation to our experience, we can derive great benefit. So let us go through the division of the truth of suffering into three: that is then the suffering of suffering, the suffering of change, and the all-pervasive suffering. So with regard the first of this threefold division (the suffering of suffering), this is what everybody understands to be dissatisfaction - whether it be a physical ailment, or whether it be that one is feeling a little bit depressed or a bit tired or a bit run down - these feelings of dissatisfaction, be they physical or mental, are what everybody understands as dissatisfaction or suffering, whether they be a practitioner or not.

The Suffering of Change

The second then is the suffering of change; this is what the majority of people in the world do not want to recognise as dissatisfaction or suffering. The reason for this is because of the way we view pleasurable experiences in the world - we view them as being nothing other than pleasurable experiences, that is to say, only bringing about pleasure, not bringing about the slightest discomfort or dissatisfaction. So if we contemplate this - what is meant by the truth of the suffering of change, we will come to understand how all experiences, when brought about in a contaminated way, that is to say, under the influence of the destructive emotions and karma are all in this nature of dissatisfaction, they do not give any lasting satisfaction. For example if we are in a cold place and we go out into the sunshine - for the first moments we are sitting or lying there in the sun, it seems only to bring bliss and joy to the mind. However, the longer we stay in the sun, what we find is that this joy, this bliss which we achieve from going out of the cold room into the sun, suddenly changes. What happens is that we get very hot, very bothered or flustered, we might get sunburn, and then through this our whole perception of being in a warm place changes - far from being something which has brought us this seemingly inherently existing bliss or joy, it is rather something which has brought us a feeling of dissatisfaction, or a feeling of suffering. So then we might want to reverse this - so we go back into an air-conditioned room, a cool room. When we arrive there, again this feeling of great joy arises in the first moment of entering such a room and it appears as nothing but bliss and joy coming from going into that room or being under that fan. But as time goes on, then we get really, really cold, we start to freeze, and then again, we have to move on to a different place, we have to get out of that room, or turn the fan off, and relieve ourselves of what appeared previously as a self-existing joyful object. We find that we need to remove ourselves from such an object in that it is not producing the joy and happiness which we previously achieved from that.

So then this is what is meant by the suffering of change; momentarily bringing bliss - this is not being denied, however it is not an everlasting bliss which is being brought about through change. The first moment is blissful because you've moved from a cold area into a warm one or from a warm area into a cold one - so it does bring about a kind of happiness, but that happiness is only the happiness of moving from one state into another - it's not a kind of self-existent or autonomously-existent joy that comes from contact with that object; rather it has the nature of change because it is brought about through contaminated action and karma. It is therefore what we call a 'contaminated' experience - contaminated through being brought about by these destructive emotions and karma. So the second moment then, or later on in one's experience of that either warmth or cold, this changes into something other than what it initially was, and through that change, brings about dissatisfaction. So it is this changing nature - changing from a momentary pleasure into something which is quite the opposite of that - which one needs to recognise in all of one's experiences, through which we will come to understand that all of our experience, whether grossly unpleasant or seemingly pleasant, have this nature of dissatisfaction, or not really delivering in the long run.

Another example we could use is if we sit down for a long time it seems very pleasant and then perhaps we get a little bit uncomfortable and we want to move around. When we get up - we stand up and stretch perhaps - we feel great joy at having stood up; but again, this is only the joy which comes about through ending the sitting down, through changing our position. Moving a little bit brings joy to the mind - we perhaps go for a walk and this movement of going for a walk again seems to be self-existing joy that is coming through the object, that is to say, walking. However, the more we walk, the more tired we become, and then eventually we want to sit down - if we are old, perhaps we have bad knees, but even if we are young, we cannot go on walking forever, eventually we become tired and we want to sit down or we want to lay down. So when we sit or when we lay down, again this brings great joy to the mind but this is a joy that is coming from engaging in that particular object, that is to say, sitting down, rather it is just a joy which comes about through plain and simply sitting down - it is not something the contact with which is going to bring everlasting joy. So this is the important point with the suffering of change - to recognise that no experience in and of itself is going to bring about everlasting joy; rather, it is in the nature of contamination, therefore it is eventually going to change into something that is quite the opposite of what we initially perceived it to be.

All-Pervasive Suffering

So then we come to the third of this threefold division, that is the all-pervasive suffering. What is meant by this the all-pervasive suffering? If we talk about the three realms of existence (that is to say, the desire, the form and the formless realm), within the desire realm (within which we find the division of the six different types of individuals), we find that there is the gross suffering of suffering. However through the form and the formless realms we find that there is not this gross suffering but up to and inclusive of the third concentration, we find that there is the suffering or the dissatisfaction, of change, but not in the fourth state of concentration. But without going too deeply into what is meant by these various states of concentration - if we just take the desire, the form and the formless realm - if one is born under the influence of the destructive emotions and karma, that is to say, in a contaminated way, within any of these three realms, then one is bound into the state dissatisfaction and suffering. So what we can understand here then by 'all-pervasive' - 'all' refers to the three realms, and 'pervasive' means that if one is born into these three realms under the influence of the destructive emotions and karma, then one is in the predicament of a contaminated existence, and then through that very nature one's lot is just that of dissatisfaction.

With regard then to this all-pervasive dissatisfaction or suffering - this is brought about through not particularly positive or negative actions but rather through neutral actions, or equanimitous actions. So what is meant here then is that this is not a gross feeling like the feeling of joy or the feeling of dissatisfaction in a manifest way, but rather is a very subtle or latent tendency to undergo such difficulties which is brought about through these karmic seeds of equanimity. So then through having been born under the influence of the destructive emotions and karma in any one of these three realms, one doesn't have any freedom to do what one wishes, that is to say, one is bound by the destructive emotions and karma. As the great master Sakya Pandita said 'freedom is joy, whereas being bound is suffering' (or 'dissatisfaction'). So if we contemplate these words by Sakya Pandita, although few in number, there is a great deal of understanding to be gained. For example we all like the word 'freedom' - if one has freedom, one can do exactly what one wants - one can go where one wants, one can eat what one wants and so forth. If one is under the influence of another, that is to say, bound by another, we have no freedom, we cannot do what we would like - we cannot go where we like, we cannot sit where we would like. This being the case then, it is not a pleasant situation to be in. Through contemplating this, we see that through being bound by the destructive emotions and karma, we do not have the freedom to do exactly what we want. Surely then we should turn our attention towards removing these fetters, or bonds, and then giving ourselves the freedom to do exactly what we would like to do. So it's good to contemplate those words of that particular master with regard to the various different kinds of suffering which we've gone through.

Four Wrong Views

So as practitioners, we should strive to understand this all-pervasive suffering. In essence we can say that the all-pervasive suffering comes about just through having contaminated aggregates ('contaminated' here referring to being under the control of the destructive emotions and under the control of the karma issuing therefrom). With regard then to the first of the Four Noble Truths of suffering, there are what is known as four aspects, or four different parts to that particular truth of suffering. With regard to the whole of the Four Noble Truths and with regard to each of the truths, they each have four different aspects; here we are just going to go through the four aspects with regard to the truth of suffering. So within this truth of suffering, we find that there are four wrong views which ordinary beings perceive and then through this perception we undergo various forms of dissatisfaction, or suffering. These four wrong views are - perceiving dissatisfaction as satisfaction; grasping onto what is impermanent as permanent; grasping onto something of a dirty nature as being clean; and then grasping onto an inherently existent self or I where such a self-existent self or I does not exist. Then through contemplating these four aspects of this first truth, we can reverse our attachment towards the truth of suffering, that is to say, we can turn our mind away from the cycle of existence.

So then if we put these four into syllogisms, then we can really clearly see how our aggregates, that is to say, our body and mind in this contaminated state are in the nature of dissatisfaction or suffering, and through this we can come to understand that wherever we are born in this state (ie a contaminated state) within any of the realms of existence, we are going to have dissatisfaction, and nothing other than that, as our lot. So with regard to the second one if we go through this first, we can say that the subject, which is our aggregates, are not something which is permanent ie they are something which is impermanent because they come about through relying upon causes and conditions; in an ordinary sense, as they rely on something else to come into existence, they cannot exist permanently, therefore they must be something other than that and the only opposite of that is something that is impermanent. Therefore our aggregates, our contaminated mind, are something that is impermanent because of being brought about through causes and conditions. Then with regard to the first of these four aspects, the subject - again, our aggregates, contaminated body and mind - are something which is in the nature of dissatisfaction because they have no freedom. And so again we can see - we are under the influence of the destructive emotions and karma, and through being bound by destructive emotions and karma, we have no freedom to do what we would like to do in our existence. Therefore the second syllogism is the subject - one's aggregates - is in the nature of dissatisfaction through being under the influence and control of the destructive emotions and karma. Then with regard to the third, again the subject is the same - viewing our contaminated aggregates - then seeing them in the nature of something which is undesirable or dirty. Then through contemplating the nature of those particular objects, we can come to this realisation and understanding. And then lastly (this is the most important one) the subject - again, the contaminated objects of body and mind - are something which is empty of a self-existence or autonomous existence because a naturally existing, or existing from its own side, self is not something which exists, ie it is completely fictitious.

So here then through this contemplation, what we come to find is that within all the different schools there are presentations of this selflessness, or this lack of an inherently existing self. So through all the different schools we can gain a greater picture of what is meant by an inherently existent self, and what the lack of that means; but in essence, and what every philosophical school agrees upon, is that this self-existent self or this autonomous I is something which cannot exist in and of itself, therefore the subject (our contaminated body and mind) lacks an inherently existing self because such an inherently or autonomously existing self is not something which exists. So these then are the four aspects of this first truth (that is the truth of suffering) and by contemplating the faults of grasping onto something as joyful which is in the nature of suffering, grasping at something as permanent which is actually in the nature of impermanence, grasping at something as clean which is actually in the nature of being dirty, and grasping at something as inherently existent, when in actual fact, it doesn't exist in such a way - through contemplating the faults of those four false views, we can reverse them and through reversing them we can put a stop to the first of the Four Noble Truths, the truth of suffering.

Fully Qualified Renunciation

So going back to our root text we read:

Leisure and opportunity are difficult to find,

there is no time to waste.

Reverse attraction to this life, reverse attraction to future lives,

think repeatedly of the infallible effects of karma and the misery of this world.

So we have just gone through the misery of this world (this can also be translated as 'samsara', or 'the cycle of contaminated existence'), and then through the contemplations we have just gone through we can slowly begin to turn our minds away from this life and put them towards thinking about future lives, and then finally, turn our attention away from our future lives and think more of achieving liberation from the cycle of existence. So through our contemplations on the misery of the world (as it is translated here) what is the sign that we have actually generated the mind striving for liberation? So we read the next stanza:

Contemplating this,

when you do not for an instant wish for the pleasures of samsara,

and day and night remain intent on liberation,

you have then produced renunciation.

So here then through contemplating the truth of suffering, and then 'when you do not wish for an instant the pleasures of samsara'. So here it's important to understand what is meant by 'do not for an instant wish for the pleasures of samsara'. What we can undergo is a strong feeling of renunciation and wishing to be free from the cycle of existence, and then in the next moment we want to do something which is very much within the cycle of existence, or very much concerned with the pleasure of cyclic existence, or samsara. So this is a sign that we haven't gained the fully qualified wish to achieve renunciation, or the fully qualified wish to achieve liberation from the cycle of existence. The next two lines read 'and day and night remain intent on liberation, you have then produced renunciation'. So when we are continually thinking of achieving liberation from the cycle of existence, it is at that moment that we have generated the fully qualified renunciation; at any time during a twenty-four period, we are always concerned with liberation from the cycle of existence - it's at that point we have generated the fully qualified renunciation. As is mentioned in the Letter to a Friend, we should be like a person whose hair has caught fire; if a person's hair has caught alight, whatever they are doing - whether it be important work or some kind of hobby - that all gets thrown to one side, and one's whole attention and one's whole time and action is concerned only with one thing, that is putting out the fire on one's head. So in the same way, we should have renunciation like that, within which all other work apart from work which is going to lead us out of the cycle of existence can be easily left aside, and we remain single-pointed and steadfast in our attitude of striving for liberation from the vicious cycle of existence. So it is at that point that the fully qualified mind - wishing to go forth from the cycle of existence, or renunciation, has been developed in our being, or mind.

Bodhi-Mind

The next stanza then reads:

Renunciation without the pure bodhi-mind does not bring forth

the perfect bliss of unsurpassed enlightenment.

Therefore the wise generate the excellent bodhi-mind.

So here, even if one has generated the fully qualified renunciation (that is to say, wishing to escape from the vicious cycle of existence), if one doesn't contemplate the dissatisfaction of others, one's kind mother sentient beings, then no matter how much renunciation one has, this is not going to bring about the state of having abandoned the most subtle abandonments, and having gathered together all the most excellent qualities, that is to say, the state of buddhahood, or unsurpassed enlightenment. Therefore the wise, seeing that being without the bodhi mind (that is to say, bodhicitta) is not going to bring about this state of unsurpassed or highest enlightenment, strive to generate within their existence, or within their mind, this wish to achieve buddhahood for the sake of all sentient beings, this mind of bodhicitta.

So then in order to achieve the state of buddhahood, or unsurpassed enlightenment, one needs two factors - method and wisdom. So as is quoted in the sutras, method without wisdom is bondage and wisdom without message is again, bondage. So what this tells is that we cannot achieve buddhahood through just one, either wisdom or method - we need both of them in union to achieve unsurpassed enlightenment. This is also echoed in Chandrakirti's book The Entrance to the Middle Way where he gives the analogy of the crane - so when a crane flies through the sky, he does so in dependence on both wings; if there is a fault with either of the wings, then the crane will not be able to fly from the east to the west or wherever. So in the same way, in order for the crane-like individual to 'fly' to the state of omniscience, one needs both 'wings' of method and wisdom unified together in one practice.

This is again mentioned in the Abhisaymamalankara where it says that the final, or ultimate, peace is brought about not through just contemplation on the nature of existence (that is to say, on selflessness), but rather is brought about through a dual practice of wisdom and method. We can here see a fault in those foe-destroyers of the hearer lineage in that they practise fully qualified renunciation and in addition to that meditate single-pointedly upon selflessness or suchness, and through that they achieve a lesser state of emancipation, or lesser nirvana. So then as we are not striving for this lesser nirvana but rather for a higher nirvana, we need to add something else to our practice, and this additional practice which we need to utilise is this mind of great compassion or 'the great lord of the minds'. This practice, in dependence upon which the welfare for all sentient beings is brought about, can thus take us to the end of the path of peace, that is to say, to the highest state of enlightenment. And if we look at the resultant state, then the various emanation bodies which come forth through the Buddha's activities, again, these solely come about through familiarisation with this mind striving to bring about benefit for others, the great mind which strives to remove others' pain or this great mind of bodhicitta. In this resultant stage, the Buddha can emanate various emanations for the benefit of others; so this is a result of training oneself in the bodhi mind.

So then we need to generate this bodhi mind. So there is a quote from the Mahayana sutra Alankara which says: ...[end of side - tape breaks here]

…colours and lights going here and there, we think 'oh, that is a nice, magical being, I want to become just like that magical individual'. So this is not the bodhi mind, the correct attitude for achieving full enlightenment, rather, this is just a selfish wish to become something rather odd! However, as individuals striving for buddhahood we need to have two qualities. The first quality is viewing all sentient beings with a mind of great compassion, wishing to free them from the predicament of suffering in which they find themselves, and it is said that the stronger one's compassion, the easier it is to bring about this bodhi mind. So the first cause, or first necessity, is bringing about this bodhi mind. The second one is a mind which is bent on achieving full enlightenment to be of maximum use to other sentient beings. So one needs to have these two contemplations together in order to achieve buddahood, these are the two crucial points which one must have - the mind wishing to liberate sentient beings from their suffering, and then a mind which is determined to achieve full enlightenment in order to bring this about in the best possible way.

The Predicament of Sentient Beings

In order to bring about this feeling of wishing to liberate sentient beings from their predicament, or their lot, of suffering, then we need to understand what is meant by their dissatisfaction or suffering. Then the next line of our root text reads:

Swept by the current of the four powerful rivers,

tied by strong bonds of karma so hard to undo,

caught in the iron net of self-grasping,

completely enveloped by the darkness of ignorance.

So here then if we use the first analogy 'swept by the current of the four powerful rivers'. So if we use this imagery of four really strong rivers flowing very fast, then caught within the combination of those four rivers. Here the 'four rivers' are four factors which hold sentient beings in the state of dissatisfaction, or suffering. So these are desire, views (wrong views), existence in and of itself, and then ignorance. So if we look at these four - ignorance is the initial cause of all the other destructive emotions. So it is said the first moment is ignorance - conceiving something in a wrong way - and that confusion brings about all the other destructive emotions and thereafter all the actions that are entered into through the force of those wrong thoughts and then thereafter the various karmic results of those actions. As for desire then, there are various kinds of desire - there is the strong desire which makes one's mind change from something peaceful to something which is completely intent on one object, there is the desire of carefully planning how to gain an object which one wants and so forth. Then with regard to the various views, what is meant here by 'view' is wrong view. Wrong view here can be divided into five, such as the general wrong mind, or wrong consciousness, and so forth. Then with regard the third, existence in and of itself - here, what is meant by existence can also refer to the cycle of existence, or samsara, and can also refer to karmic actions in the dormant and also in their fully ripened states. So those four rivers combined as one are what is carrying our kind mother sentient beings along. So if we imagine somebody who has fallen into a fast-flowing river or fallen into the rapids - if they are able to shout for help then that is one thing, and if they are able to swim then there is every possibility that they will be able to reach the banks of the river and get out of this fast moving current.

However, this is not the case because as the next line of the root text tells us - 'tied by strong bonds of karma so hard to undo'. So not only are these kind mother sentient beings swept along in this rapid, but in addition, their hands and feet are tied up, they are completely bound up with very tough ropes and cannot possibly move. And you would think then that even if this is the case they might be able to get out of these bonds by contortion or suchlike, but this again is not the case because in addition to being bound, (as the third line reads) they are 'caught in the iron net of self-grasping'. So here 'iron net' can also be translated as 'cage'. So not only is one bobbing along completely bound by the strong bonds of karma, but one is also wrapped in this chain-mail of self-grasping. And you would think then that as this is the case, if one was fortunate enough to come into contact with a fisherman sitting on the riverbank, by calling out to him, if he is a kind-hearted individual, he might throw us a line or try to hook us out. However, this is again not the case because as the fourth line reads - 'completely enveloped by the darkness of ignorance'. So if we look at this example - someone has been throw into a rapid, is being swept along by this powerfully moving water, not only are they bound up but they are wrapped in chain-mail and it is the middle of the night, so there is no chance even to come into contact with somebody on the riverbank who one could call to and request assistance because it's in the middle of the night, it's very dark, and nobody goes to the riverbank at that time. So in the same way there are the four powerful rivers which we have just gone through (the four causes of the cycle of existence), then fettered by bonds of karma, wrapped in this chain-mail of self-grasping, completely enveloped in the darkness of ignorance - that is the pitiful state of one's kind mother / father sentient beings.

Physical and Mental Suffering

So as is mentioned in Aryadeva's book The Four Hundred Verses, the aristocrats are beset with mental suffering whereas the ordinary person is beset with physical suffering. Whatever kind of suffering one is engaged in, one should daily try to put an end to such suffering. So here then we can divide dissatisfaction grossly into two, that is to say, dissatisfaction, or suffering which is physical and then that which is mental. Then those kind of aristocrats, those who have very fine jobs, they are individuals who do not suffer so much physically - they have nice places to live, nice food to eat and so forth; however they have a lot of mental torment - thinking about the various businesses which they are involved in, the various meetings they have to go to and so forth - that is their lot of suffering. Whereas for an ordinary working person there is not so much mental worry about rushing to meetings, buying and selling stocks and so forth, but there is physical suffering in that one has to work for one's living so therefore one engages in various strenuous activities. This is not something which is easily seen in the West, but in India if you look around building sites there are no cranes or lifting devices - bricks are carried by the local people stacked high on the head and the cement is carried on the back by the coolies and so forth. So if you see the very low-paid, low caste people in India you will see that they go through immense physical difficulty, but when they sit down there is not so much mental dissatisfaction or suffering, but rather their lot is that of physical difficulty. Then as the text goes on to say, whatever kind of suffering it is - whether mental or physical, one should daily engage in a practice which is going to bring about the thorough removal of that dissatisfaction.

So using that quote from The Four Hundred Verses then, a person who has wealth when viewing how poorer people live might think 'living such an aristocratic life is not all it's cracked up to be - living in the open, living a pauper's life is something that is quite delightful. I think I'm going to give up everything and go and live as a pauper!' And then the paupers, or the working people, when viewing the aristocrats, or the wealthy individuals, think 'oh, we have such a hard time - all this work we have to do but those guys are just sitting around, they have nice food to eat, servants to wait upon them, nice comfortable beds and so forth. How great it would be to achieve such a status!' However, if we look at that with a vaster view, we see that both kinds of individuals are undergoing dissatisfaction, and the dissatisfaction which they are undergoing is same in essence but different in aspect; different in aspect in the sense that for a poorer individual it is physical but for a wealthy individual it's mental. But the contaminated actions which have brought about their very existence are ones within which one can never find any permanent peace; rather as we mentioned earlier, the first moment can be somewhat peaceful or joyful, but then as soon as that is over with, the experience changes into something other than what it initially was. So viewing the cycle of existence, or samsara, as the product of contaminated actions, contaminated destructive emotions and so forth, then we should strive to put an end to all dissatisfaction and the causes of that dissatisfaction, not just one particular kind of those various kinds of dissatisfaction. We should strive to abandon the whole of the cycle of existence, and this is echoed in the prayer to the lineage gurus of the Lam-rim genre of teachings by Tsongkhapa when he says that one should strive to abandon the cycle of its existence through seeing its faults, through seeing how it is impermanent and through seeing how it is not something that is very stable.

harma [Tib: chö] means to hold, or uphold. What is it that Dharma upholds, or maintains? It is the elimination of suffering and the attainment of happiness. Dharma does this not only for us but for all other sentient beings as well.

harma [Tib: chö] means to hold, or uphold. What is it that Dharma upholds, or maintains? It is the elimination of suffering and the attainment of happiness. Dharma does this not only for us but for all other sentient beings as well.