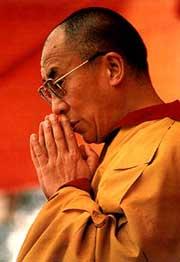

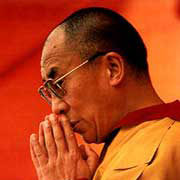

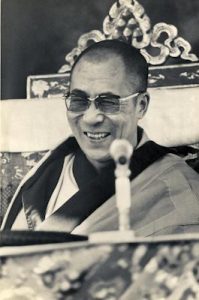

| A teaching by His Holiness the Dalai Lama prior to a ceremony for generating the mind of enlightenment, Washington, New Jersey, May 7, 1998.Lightly edited by Sandra Smith, February 2013. |

I would like to extend my greeting to all of you.

I would like to extend my greeting to all of you.

Yesterday when I arrived here it was raining quite a lot, but today it is quite different and pleasant. Perhaps half of you have come here partly to have a good time, for a holiday, so if you wish to stay for the whole talk or if you wish to walk around and take it easy, please do so.

The teaching that is going to take place here today is preceding the ceremony for taking the generation of the mind of enlightenment and for that I will be doing some preliminary recitations including the recitation of the Heart Sutra.

In the context of giving the teachings, both on the part of the person who is giving the teaching and the people who are receiving the teachings, it is very important to ensure that you have the right motivation. Therefore, for a Buddhist teaching it is very important that you take refuge in the Three Jewels and commit to the ideals of bodhicitta.

So please recite the refuge formula.

[Refuge prayer in Tibetan.]

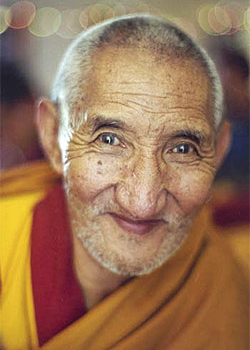

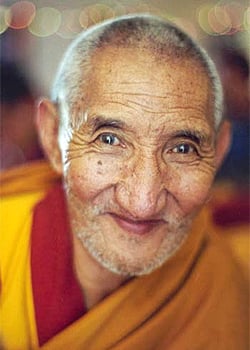

I have visited this place several times and also I have had the opportunity to give teachings at this place several times. When I look around here today, one thing that I notice is the change in the trees. Some of the trees have really grown; some of them have really spread their roots. So, this points out to us and reminds us of the basic principle of impermanence, the transient nature of life. This is also something that we can remember if we think about the founder of the center, the late Geshe Wangyal-la, who is no longer with us. All of these things point towards the nature of impermanence, the transient nature of life. This transient nature and the process of change that we go through, that everything goes through in time, is something that no-one and nothing can stop. This is a basic fact of reality; a basic fact of existence.

Now what we do, what control we have in our hands, is how we utilize this time, which is constantly going through change. If we utilize our time for a more beneficial and positive purpose, we give our existence some kind of purpose and meaning. If we use it for destructive purposes, we create harm for ourselves and others. If we just lead a life with no mindfulness, we just completely have no sense of direction. So, the only thing that we have in our hands is how we utilize the time. So, wouldn’t it be wonderful to utilize whatever remaining time that we have in our existence, in our life, towards something that is noble and meaningful; something that is purposeful?

However, leading our life in a purposeful and meaningful way does not necessarily mean we have to lead a religious life in the sense of a religious belief or with religious faith. The key or essence is to lead a life which is grounded in the principle of helping others, if possible. If not, at least refraining from harming others. So, that is the key.

If we wish to create a sense of purpose, we can make our existence meaningful on the basis of a religious faith. Of course, on this planet there are so many different major world religious traditions, so we can pursue these paths through different traditions. However, it is important for the followers of these religious traditions to utilize, to implement the essential teachings of whatever religious path we are following in daily life.

If we can integrate the essential teachings of the religious path that we subscribe to and follow into our day-to-day experience, then of course there will be tremendous benefit.

Today, in the context here, the religious teaching that is being given is a Buddhist teaching, because this is a Buddhist center. Although many of you may already be aware of this, the key message of the Buddhist teachings is to try to seek a path to happiness and joy through a method that involves primarily bringing about discipline of the mind. This discipline of mind really brings about a transformation of the mind, which is the key path to obtaining happiness according to the Buddhist approach.

From our own personal experience we know that the more conviction, the more convinced we are of the value of a particular goal that we are pursuing, the greater our commitment and the greater our desire to attain that. In some cases, the commitment to achieving that goal is so strong that even if we are tempted to be distracted or diverted, there is a check, so we can follow the path without distraction.

What becomes important in this context for us here is to ensure that our wish to obtain that goal is grounded in a firm conviction, not only in the value of that goal, but also that our conviction is grounded in some personal experience and some valid reasons. The stronger it’s grounded in such valid reasons and personal experience, the more firm our commitment to that goal will be. Therefore in the context of Buddhist spirituality, the Buddhist religious path, understanding the nature of reality becomes very crucial.

Given that understanding the nature of reality becomes crucial for a Buddhist religious path to achieving the goal of ultimate liberation, what becomes important for Buddhist practitioners is not to be deceived by whatever perception we have. We should not be deceived by the level of appearance. Even from our own personal experience in day-to-day living, we know that appearance does not necessarily always convey the right picture of reality. Often in our day-to-day interaction with life there is disparity or a gap between how things seem to us and how things really are. This is really the basis for the Buddhist emphasis on developing such deep understandings like the nature of the two truths. Understanding the nature of reality is crucial, and in order to arrive at such a proper understanding we need to appreciate that sometimes appearance is not the true picture of reality. Therefore, having the sensitivity to appreciate that there are different levels of reality becomes critical.

The whole purpose of trying to seek a deeper understanding of the nature of reality based on the concept of the two truths is to bring about our ultimate spiritual aspiration of attaining lasting happiness and overcoming suffering, therefore, the teachings of the two truths are directly related to the Buddhist teachings of the four noble truths.

Once we look at the Buddhist teachings from this kind of angle or perspective, then we really appreciate the principal significance of the Buddha’s teaching on the four noble truths at his first public ceremony. Through teaching the four noble truths, he lays down the whole foundation or framework of the entire Buddhist path to enlightenment.

In the second public ceremony, the Buddha’s key teaching was the two truths. Although the two truths as a philosophical concept is something that is found not just in Buddhist teachings but also in non-Buddhist schools, it is in the teachings of the second public ceremony that we find a presentation of the highest level of understanding of the two truths. This addresses the fundamental issue at the heart of our existence as individual human beings or as sentient beings.

Now that we realize that the teaching on the four noble truths presents two sets of causality—one set that deals with the causality of suffering and its origin, and the other set which deals with the causality of cessation, the cause of that cessation, which is the path—we can raise the question, “Why?”

What was the significance of the Buddha teaching the four noble truths to begin with? The significance of that is to address the fundamental issue of our existence as individual human beings or as sentient beings. At the heart of our existence is this instinctual or innate desire to seek happiness and to overcome suffering. So, sentient beings who possess these natural instincts exist.

This suggests that naturally there exist sentient beings who possess this instinctual desire to seek happiness and to overcome suffering, and that really is at the basis. So the question can be raised about the nature of those sentient beings. We find a reference in one of the tantras where Buddha speaks about the beginningless and endless continuum of mind, that is said to be the ever-good or eternally good. The reference to the beginningless and endless continuum of consciousness or mind is that from the Buddhist point of view, there is nothing that exists outside the bounds of causation. Every event and every thing must come into being as result of causes and conditions. This is also true of consciousness, as it is true of the external world. In the case of a material phenomenon, not only must the object have a cause, but also there must be some substance which maintains its continuum from one instance to another. Buddhists call this a substantial cause or material cause—a cause which maintains the continuum.

Similarly, in the case of consciousness—of mind or mental phenomena—there must be a continuum, and not only must there be a continuum, but also that continuum must be maintained on the basis of entities which share the same nature. A physical entity cannot become a continuum for a mental entity or mental phenomena. So it is on that basis, as far as the continuum of consciousness itself is concerned, there is nothing that can really destroy that continuum, therefore, it is also endless.

However, this is not to say that every instance of consciousness or mental event is beginningless or endless. Of course, when we talk about consciousness—mind or mental phenomena—we must appreciate that there are so many different levels of subtlety and coarseness. For example, many of the gross levels of consciousness, such as our sensory experiences and many of our thought processes, are time-bound; they are contingent on that. Many of these aspects of consciousness are contingent upon specific additions, specific organs and so on.

Within the continuum of consciousness, there must be something unique to consciousness, that makes the first instance and the second instance and so on possess that nature of being an experience, which is called the luminous nature. There must be something in the nature of mere experience or in the nature of mere awareness, and it is on that basis that we speak of the beginningless continuum and the endless continuum. That faculty, that quality of pure awareness or mere experience is not contingent upon any physical conditions and neither is it contingent upon any specific time, so it is from that point of view that consciousness or mind is said to be beginningless and endless.

In Buddhism, when we speak about the nature of self—the person or I—that self or I is something that is designated upon the basis of this continuum of consciousness. So, just as the continuum of consciousness is said to be beginningless and endless, therefore in Buddhism, the person—the self or I—that is designated upon that continuum of consciousness is also said to be beginningless and endless.

The method or means by which we can fulfill the aspirations of that self or that person which is designated upon the continuum of consciousness must come about on the basis of some transformation of that mind or consciousness.

This fact is very forcefully demonstrated in the Buddhist teachings on the twelve links in the chain of dependent origination. The teachings say very explicitly that it is our fundamental ignorance that creates the whole chain that eventually makes the cycle of the twelve links. Ignorance leads to volition, volition leads to karmic consciousness and so on and so forth, so it is the fundamental ignorance that creates the whole cycle of unenlightenment.

However, it is through the elimination of ignorance that we reverse the cycle and thus create a process towards enlightenment. When Buddha taught the twelve links of dependent origination, we were never given the impression that although fundamental ignorance lies at the root of the whole cycle, we can eliminate ignorance simply through a prayer or simply through adopting certain physical discipline or some form of physical behavior. We are taught that we can begin the process of reversing the cycle only through cultivating the right insight that sees through the delusion created by ignorance. So in brief, ignorance lead to unenlightenment and knowledge, the opposite of ignorance leads to...

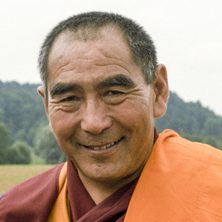

[At this point, the Dalai Lama interrupts the interpreter, Geshe Thupten Jinpa, and speaks briefly with him.]

Geshe Thupten Jinpa: Sorry...Ignorance leads to suffering, unenlightenment. [The Dalai Lama laughs] The opposite of ignorance, which is knowledge, leads to happiness or enlightenment.

His Holiness is saying he realizes that it is not only him who sometimes uses the wrong word.

His Holiness: Using the wrong word, not only me alone, but some people also there.

Geshe Thupten Jinpa: If you look at some of the epistemological texts, these texts speak of different fruits of valid knowledge or valid cognition, and in these texts, attainment of liberation or enlightenment is identified as the long-term fruit of cultivating knowledge or valid cognition. So what seems to be true is that if we examine this carefully, much of our experience of suffering and confusion really comes from states of mind which are ultimately deluded, and much of our experience of joy and liberation and enlightenment really comes from stages of thought or states of mind which are not deluded, which have their roots in some kind of valid experience or valid knowledge.

What becomes evident through all of this discussion is the fact that even for our spiritual path, cultivating the right knowledge and insight seems to become really crucial and critical. In some sense, we are aware of this fact, because even conventionally speaking we all appreciate the value of education and knowledge. The higher the level of education of the person, the better informed that person will be to cope with the challenges of life. In some sense, we do appreciate this basic point.

So we can raise the question, how does cultivating the knowledge and the insight help us eliminate fundamental ignorance? Here, when we talk about opposing forces and how one expels the other, we can use the analogy of light and darkness—illumination and darkness. The moment the illumination, the light, is switched on, the darkness is dispelled, so here we have an analogy.

Similarly, when we think about the different forms of mutual exclusivity, for example, in the case of our thoughts, if we know that something is a tree or that something is not a tree. If we know that something is not a tree, then so far as our thoughts relate to that particular object of concern, we can at that very instant never have the possibility of thinking, “That is a tree.” One thought, by the simple fact of its occurrence, by definition excludes the possibility of other.

There is a similar kind of relationship between ignorance on the one hand and wisdom or insight on the other. Ignorance here is not a case of mere unknowing, but rather it is an active case of perceiving things in a way that they do not exist. So when we cultivate the opposing thought, which is true knowledge or insight, given that these two thoughts oppose each other, the only difference is that insight is grounded in valid cognition. Just as we have insight that things and events do not possess some kind of independent existence, this also corresponds to the actual reality, because things do not possess an independent existence.

On the other hand, fundamental ignorance misperceives things as possessing an independent existence, but this does not have any validity—it does not have any ground or any support. So, when we compare two opposing thoughts which are directly opposed to each other, whichever has the validity and whichever has the support grounded in our experience is going to be more powerful. So, it is in this way that ignorance will have to be eliminated.

These reasons make it very important in Buddhism to cultivate an understanding of emptiness, and this is why emptiness becomes important in the Buddhist path. Of course, depending upon different interpretations, there are different ways of understanding what emptiness really means according to the Buddhist teachings. We understand that the emptiness as taught by Nagarjuna—where in the final analysis, emptiness is understood in terms of dependent origination—that is the highest level of understanding of the teachings on emptiness.

[Missing text]

Dependent by nature suggests that things are devoid of independent reality, or intrinsic reality. They are devoid of inner existence and identity, and this is what is meant by the Buddhist teachings on emptiness. It doesn’t mean that things do not exist. It simply means that things do not exist with some kind of independent identity or existence. So the nature of dependent origination is used as the final proof that things are empty, in the final analysis.

The thought which believes in the independent, intrinsic reality of things and events is known in Buddhism as the self-grasping thought or attitude. This we know is one source of much of our confusion and much of our ignorance. We also know that there is another element which is also one of the major origins of much of our suffering and problems. We are not only grasping at some kind of true existence of things and events and also at oneself, but we also have an attachment to the self which the Buddhists call the self-cherishing thought. This is a thought which cherishes one’s own self-interest and is completely oblivious to the well-being of others.

However, this is not to say that any form of self-regard is a source of suffering, because we do need a sense of self and also we do need our thoughts to have an element of self-regard. It is on the basis of a strong sense of self that we can proceed with many of the methods for attaining liberation: salvation, helping others and so on.

Now there is a problem when this form of self-regard becomes extreme to the point where we are prepared to exploit others; we are prepared to totally sacrifice others’ well-being in pursuit of that self-interest. In that form of extreme self-regard, a sense of self is a powerful problem.

His Holiness is making the point that if you don’t have any experience of caring for yourself, how can you even begin to care for others, because there is no real basis from which you can engage with others.

How do we overcome this excessive form of self-cherishing, that is prepared to sacrifice and exploit others’ well-being? The effective way to overcome this is through cultivating thoughts that cherish the well-being of others.

We can say that these two forces—the certain grasping at the self-existence of things and the self on the one hand, and also this excessive form of self-cherishing attitude —these two are said to be like two poisons that pollute from within. We could almost say that these two are poisonous trees that are growing in us.

Through this we can appreciate that the essence of our spiritual path should be the practice of cultivating compassion and love, which counteracts the self-cherishing, and also the practice cultivating correct insight into emptiness—the knowledge of emptiness which counteracts the other force. These two should not only be the essence of the teaching, but the key elements of our individual practice.

The day before yesterday I participated in a symposium on neuro-science and Buddhist meditation at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York. One of the speakers made a presentation where he showed an empirical study that was done, which seems to suggest quite conclusively that those people who have a tendency to use more self-reference terms, such as “I”, “me” and “mine” in a much higher proportion than the average person, have a much higher degree of self-involvement. Those people tend to have more health problems and also have much more hyper- kind of personality, and they are more prone to aggression and so on, including a much higher possibility of an earlier death.

This seems to suggest that not only Buddhist meditation on selflessness and counteracting the self-cherishing thoughts through cultivation of thoughts cherishing others’ well-being; not only do these kinds of practices have the benefit of leading to Buddhist liberation, nirvana, but even within this lifetime, even in immediate terms, there seem to be visible, beneficial effects. Because of this, just before the teaching, I told one of my friends, that if this is true then maybe many of the ritual practices that are aimed toward longevity—visualizations and meditations which involves prolonging one’s life, through focusing on one’s life—perhaps these may be counterproductive because the focus is on oneself whereas the focus should be on the others.

If we think carefully, it seems that the more self-involved we are, the more self-absorbed we are, thinking, “Oh yes, me, my problem, my this and my that,” it seems to have an immediate effect of narrowing our focus down to some tiny spot and reducing everything to that. It’s almost as if our vision is blurred, even to the point of being burdened, being pressed down by some heavy load. If we shift our focus from ourselves to others and think more about others’ well-being and welfare, immediately it has a liberating effect, because of that shift of focus. It gives rise to some kind of strength and also it makes us feel more expansive. Even if we are facing problems and we are aware of our own problems, somehow that very shift in the focus provides the space so the problem that seemed enormous earlier, now seems to be much more manageable. It seems to be less significant than it was before. This is the truth.

Since the main actual teaching here is the generation of the mind for enlightenment you should cultivate the right attitude, which is to put the focus on others, not on oneself and spread it out, extending it to all sentient beings, if possible. For the benefit of all sentient beings, make a strong commitment that you will ensure that this altruistic mind never degenerates.

As usual, for the ceremony of generating the mind of enlightenment, you should visualize here in your presence, the Buddha, the teacher, and all the bodhisattvas of the past and also the great masters of India and Tibet, such as Nagarjuna, Asanga and so on, and focus on them. Cultivate strong faith and admiration in them and then imagine that you are surrounded by all sentient beings and then focus on them. You should reinforce within you a strong sense of empathy and compassion towards their suffering and their problems, and then cultivate the thought, “For the benefit of all these sentient beings, I shall generate the mind of enlightenment in the presence of all the buddhas and bodhisattvas, and the great masters of the past. As a preliminary to that generation of the mind of enlightenment, I need to overcome all obstacles, therefore I shall engage in the preliminary practices, such as the purification of negativities, accumulation of merits and so on.”

This will be performed through the recitation of the preliminary practices, which will be done in Tibetan. When the recitation is being done, on your part, you should imagine that you are going through these practices of purification and accumulation of merits.

[His Holiness recites prayer in Tibetan.]

I believe that a small sheet has been distributed to all of you with three verses in English. The first verse deals with taking refuge and the second verse deals with the generation of the mind of enlightenment. I believe that they are citations from one of the tantras.

The first verse basically states that, motivated by the wish to free all beings, “I will go for refuge to the Buddha, the Dharma and Sangha, until I attain full enlightenment.”

The second verse states that this is reinforced with compassion and is grounded in true insight or wisdom, “I shall generate the mind for enlightenment in the presence of all the buddhas here today.”

The wisdom of emptiness, the insight of emptiness, reinforces compassion because through the cultivation of the right insight, the wisdom of emptiness, we will gain the awareness or the knowledge that grasping at true existence is a form of delusion. Because it is a form of delusion it is something that can be corrected—it is something that can be removed or eliminated. Once you gain the conviction of the possibility of eliminating that delusion from within, then your compassion toward sentient beings who continue to be deluded, who continue to be deceived by such forms of delusion will increase ever more, because you know that there is a way out. Sentient beings continue to be chained in the cycle, so of course this true insight into emptiness will reinforce your compassion towards other sentient beings.

The mind for enlightenment, or bodhicitta, is a state of mind that is altruistic and is derived on the basis of true aspirations. One aspiration is to fulfill the welfare of all other sentient beings, and the other aspiration is to seek full enlightenment for the sake of fulfilling the objective of helping others. So it is on the basis of these two wishes that we cultivate the mind that seeks full enlightenment. This is called bodhicitta or the mind of awakening.

The third verse is really a verse of dedication and also an aspirational prayer. This is from Shantideva’s Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life, the Bodhicaryavatara.

When you recite these three verses, you should dwell on their meaning. In the first verse, you are taking refuge in the Three Jewels; in the second verse, you are cultivating generating the mind for enlightenment; and in the third verse, you should have a strong sense that, “Now that I have generated the mind of enlightenment, I shall follow in the footsteps of the great bodhisattvas, and share in the powerful sentiments expressed in this verse, as long as space remains.”

We will do the recitation in Tibetan and while the Tibetan recitation is being done, you should read it all together in English.

With a wish to free all beings

I shall always go for refuge

To the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha,

Until I reach full enlightenment.Enthused by wisdom and compassion,

Today in the Buddha’s presence

I generate the Mind for Full Awakening

For the benefit of all sentient beings.As long as space remains,

As long as sentient beings remain,

Until then, may I too remain

And dispel the miseries of the world.

I think whenever you have spare time, it would be very effective and beneficial to recite these three verses and reflect on their meaning. In that way you can experience the benefit. There is a Tibetan expression which states that the mind follows familiarity. So it is through constant familiarization and constant practice that something becomes more natural, easier and more applicable. So with that, today’s teaching is over. I would like to ask all of you to be happy.

His Holiness [in English]: Of course I believe the ultimate source of happiness is within ourselves. I think it is very important that our mental state remains calm, peaceful, then the external disturbances will not much disturb our internal peace. So therefore while we are earning money or some other things, I think it is equally important to pay more attention to our inner values, to be somewhat balanced. We should not be a slave of money. So, I think a happy balance. Of course, money is very important, hmm? [Laughter.]

Geshe Thupten Jinpa: You may be interested to know that Tibetans have a nickname for money; it is called, “that which by which all the wishes are fulfilled.” [Laughter.] So, the Tibetan expression translates as, “that which makes everybody happy and that which makes all the wishes fulfilled”.

His Holiness [in English]: So, as I mentioned before in the beginning, I think it is very, very important to be a warm-hearted person, a good-natured person, with more sense of caring for others. Ultimately, you get more happiness.

So, as I think—our old friends, I think you often heard before, I’m always telling people—I myself feel that if you are going to be selfish, you should be wise-selfish rather than foolish-selfish. So I think that’s very important. If you take care more of others, ultimately you get the benefit. That’s all. Thank you very much.

[Recitation of dedication prayers in Tibetan.]

Many billions of years elapsed between the origin of this world and the first appearance of living beings upon its surface. Thereafter it took an immense time for living creatures to become mature in thought and in the development and perfection of their intellectual faculties; and even from the time men attained maturity up to the present many thousands of years have passed. Through all these vast periods of time the world has undergone constant changes, for it is in a continual state of flux. Even now, many comparatively recent occurrences which appeared for a little while to remain static are seen to have been undergoing changes from moment to moment.

Many billions of years elapsed between the origin of this world and the first appearance of living beings upon its surface. Thereafter it took an immense time for living creatures to become mature in thought and in the development and perfection of their intellectual faculties; and even from the time men attained maturity up to the present many thousands of years have passed. Through all these vast periods of time the world has undergone constant changes, for it is in a continual state of flux. Even now, many comparatively recent occurrences which appeared for a little while to remain static are seen to have been undergoing changes from moment to moment.

Just like me, others don’t want even the slightest suffering and they want to experience happiness, but that happiness is never enough. Therefore, myself and others are just the same.

Just like me, others don’t want even the slightest suffering and they want to experience happiness, but that happiness is never enough. Therefore, myself and others are just the same.

Searching for happiness

Searching for happiness The wisdom and form bodies of a buddha

The wisdom and form bodies of a buddha