|

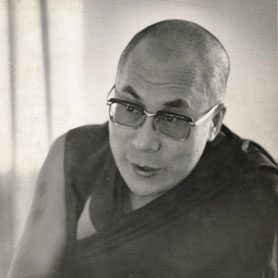

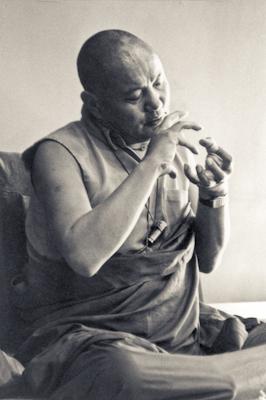

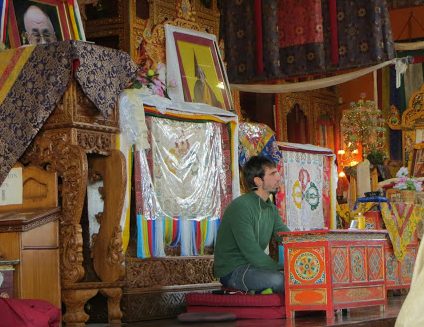

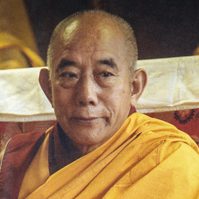

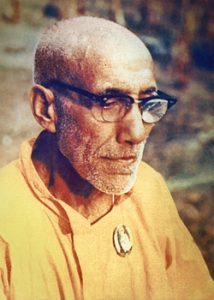

Khen Rinpoche Lama Lhundrup, former abbot of Kopan Monastery, gave this teaching on the eighteen root bodhisattva vows at the 20th Kopan Course, held in December 1987. The teaching is translated by Ven. Tsen-la and lightly edited by Sandra Smith. You can read a Prayer for the Quick Return of Khen Rinpoche Lama Lhundrup by Kyabje Lama Zopa Rinpoche on the LYWA website. A copy of the Bodhisattva Vows is available from the FPMT Foundation Store. |

Whether we reflect on things from the point of view of self or from the point of view of others—whatever point of view we have, our main objective is to achieve enlightenment at any cost.

Whether we reflect on things from the point of view of self or from the point of view of others—whatever point of view we have, our main objective is to achieve enlightenment at any cost.

As explained in the lam-rim teachings, the suffering nature of our existence in samsara and its causes are the result of our own selfish attitude or self-cherishing mind. The conclusion or the main essence of the lam-rim teachings is to generate a strong motivation—the strong thought to benefit sentient beings at all costs. The reason for this essential conclusion is that all our happiness, including the smallest, is solely due to the kindness of others.

The benefit we can accomplish is to fulfill what others wish and repay their kindness. What others want at all times is happiness and what they don't want is suffering and pain. Just as it is for others, it is also the same for us, and as it is for us, it is the same for others as well.

We learnt in the teachings on the graduated path to enlightenment that to find happiness and to eliminate suffering, the responsibility belongs to us completely. Although we have complete responsibility for fulfilling all the happiness of others and eliminating all their suffering, we do not have the potential to fulfill this at the moment.

Is it possible for me to actualize or to attain such potential? We can achieve this potential. Is a person with such potential a possible phenomenon in the world? This is also a possibility. Who can we identify as such a person? That would be the Buddha himself. If we put in the effort, we can achieve such a state ourselves, because we can accumulate the causes for this result, enlightenment. In order to achieve the result of enlightenment, we need to train in the methods to achieve it.

The main method to achieve enlightenment is bodhicitta, the altruistic aspiration towards enlightenment generated out of the mind of compassion. Bodhicitta, the altruistic mind seeking solely the welfare of others, needs to be enhanced limitlessly. It is not enough just to habituate our mind, and generate or cultivate the altruistic mind in our meditation—besides generating the altruistic mind, we also need to actually venture into the deeds of such a mind.

The main deeds of bodhisattvas, the beings who have bodhicitta, are the observation of a high code of ethics. How quickly or slowly we achieve enlightenment is solely dependent on how purely we observe the bodhisattva vows. These vows need to be received or taken from a lama and then all the various aspects of the vows need to be observed.

Of these various aspects of the bodhisattva vows, the root vows are this set of eighteen. We must abandon:

1. Praising ourselves and belittling others.

If we have received bodhisattva vows and engage in actions such as praising ourselves with the desire to achieve material things or respect and so forth—if we have that kind of intention, and the view of gaining things that glorify our qualities and put down others—when we have bodhisattva vows and undertake such an action, then we break the root vow. This is a very brief explanation of the first vow.

This is one of the most dangerous vows, because we are likely to break this vow very easily due to our strong, self-cherishing mind. There is a danger of breaking this vow very often because of our selfishness, and also because we very easily disparage others, including our guru, when we see the slightest faults or mistakes in them.

2. Not giving material aid and Dharma.

This vow is usually broken when we are miserly. When we have an abundance of material things and somebody asks for material aid due to their great poverty or lack of something, but we refuse, then we accrue the second transgression. If we have no sense of miserliness, but refuse to give because it may cause obstacles or hindrances to our Dharma practice, then under these circumstances, not giving is validated.

Secondly, there is miserliness regarding teaching Dharma. We feel miserliness over imparting these teachings and we also feel lazy to explain the teachings sometimes. That's the second way to break the vow. The only circumstances when it is valid not to give teachings is when this would not benefit someone but would cause harm, and in that case we can refuse to give teachings. Generally, in giving Dharma teachings, the kind of people that we should teach are those with much aspiration and enthusiasm towards the teachings.

3. Not forgiving others, and even if someone apologizes, not listening to an apology.

The third vow is broken, for example, when we fight with somebody and that person apologizes afterwards or gives us a material present, but we refuse to listen out of anger, upset feelings or hatred. If we hold a grudge and refuse to accept a material gift or listen to an apology, then we break the third vow. So, for these sets of vows it is essential not to hold onto anger or a grudge after we have had a fight or disagreement. If we hold onto a grudge or anger, then it is difficult to accept an apology later on.

4. Abandoning the Mahayana Dharma.

The downfall of abandoning the Mahayana Dharma is accrued in circumstances such as when we are engaging in Mahayana practice and later we decide, “I might as well train in the Shravaka path, or the Hearer’s path, which is a faster way of attaining arhatship.” We abandon Mahayana Dharma under these circumstances.

5. Taking offerings which are meant for the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.

This occurs when we take for ourselves offerings made to the Triple Gem. This includes materials to make a statue or to print scriptures or to make clothes for statues. Of the three types of offerings, if we use offerings made to the Sangha for ourselves, no matter how small they are, then the karma is very heavy. It is said that if we take offerings made to the Buddha and the Dharma, the negative karma can be completely purified, but if we take offerings made to the Sangha, even if we purify, some result has to be experienced despite the purification. It can be something as minor as picking a flower, a twig or a leaf from the garden. We are taking that which has not been given to us.

6. Abandoning the Dharma.

This means abandoning the practices and teachings belonging to the Hearers’ Vehicle, the Shravakas, the Solitary Realizers’ Vehicle or the Mahayana Vehicle. We see one or other of these teachings as not being suitable for our practice. We may say, for example, “What's the point of meditating on the whole lam-rim? I might as well just do the breathing and contemplate on the mind. That's all!” Even just saying that is abandoning Dharma.

7. Causing an ordained person to disrobe.

This vow includes things like, for example, taking away robes that belong to monks, or causing someone else to take the robes away.

8. Committing the five immediate negativities.

We commit these “immediate negativities” when we kill our father, mother or an arhat, cause a Buddha to bleed, or cause disharmony within the community of the Sangha.

9. Holding wrong views.

Holding wrong views refers to believing in the non-existence of cause and effect, past and future lives, and the non-existence of the three objects of refuge and so forth.

10. Destroying towns, cities or places where many people are living.

We break the tenth vow if we intentionally destroy a town or city. Whether we start some sort of fire or use water or other means, we have the intention of destroying that whole town or city.

11. Teaching the profound teachings to those who are not fit receptacles.

An example would be somebody who is on the bodhisattva path and when we expound the teachings on emptiness, the person gives up or turns away from the Mahayana path. Instead of helping the person progress, we cause that individual to regress. That would be an example of teaching the profound to someone who is not ready.

12. Turning someone away from complete enlightenment.

The twelfth downfall occurs when, for example, somebody has full aspiration towards complete enlightenment and we influence the person by saying that there is not much benefit, and that it is better to work for our self-liberation through either the Solitary Realizer's path or the Hearer’s path. If we influence the person to turn away from full enlightenment through our talk, we incur this twelfth downfall.

13. Encouraging others to abandon the self-liberation vows.

The transgression occurs when we tell people that the self-liberation vows, such as the monks’ and nuns’ ordination vows, are not necessary. We tell people to just study the Mahayana Dharma and generate bodhicitta. If we talk and influence people in this way, we incur the thirteenth downfall of abandoning self-liberation vows.

14. Causing others to hold distorted views.

We incur the fourteenth downfall when we cause others to hold distorted views. An example of this is when a person has received a lot of material presents and respect through giving teachings, and out of jealousy, we feel that this person’s gains are unbearable. We say, “Why do you listen to his teachings, why do you give him so much respect and so forth?”

To differentiate the first root downfall from the fourteenth, the fourteenth one mainly arises out of a jealous mind, as the other person is getting so many enhancements, and that is causing our own downfall. We are losing out by the other person gaining and we feel unbearable jealousy over that, so it mainly has its base in jealousy.

15. Expressing a great form of lies.

This downfall means telling profound lies and saying we have realizations when we don't. An example of the fifteenth root downfall, the expression of profound lies, is when we haven't realized emptiness, but we say, "I have realized emptiness, so I am going to teach you this emptiness out of my experience."

16. Taking material things that belong to the objects of refuge.

An example of the sixteenth vow is when we intentionally fine someone who is ordained so that we gain material things. The sixteenth vow refers to any property that belongs to the Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. We either forcefully confiscate or take away property belonging to the objects of refuge, or we influence or cause someone else to take the property away. If we have a fight or a duel, or something like that, we take things belonging to the objects of refuge.

17. Laying down harmful regulations and passing false judgment

The next vow is putting together rules or disciplines that are not valid. An example of this downfall is when a gelong is practicing very purely and we make certain rules and regulations that would disrupt his progress. We do this out of jealousy for that person who is doing his practices purely, and in order to distract him away from his meditation.

Lama Lhundrup: How many have we got? Eighteen?

Students: No, seventeen.

Lama Lhundrup: Seventeen? We missed out the fourteenth one, which is disrespecting or criticizing the Hinayana teachings. Then, the other one is abandoning the bodhicitta mind. Does that make eighteen? What happened? No, I think it’s eighteen.

The Eighteen Root Vows1

1. Praising yourself and belittling others.

2. Not giving material aid or teaching the Dharma.

3. Not forgiving someone who has previously offended you.

4. Condemning the teachings of Buddha and teaching distorted views.

5. Taking offerings to the Three Jewels.

6. Despising the Tripitaka and saying these texts are not the teachings of Buddha.

7. Causing an ordained person to disrobe.

8. Committing any of the five heinous crimes.

9. Holding views contrary to the teachings of Buddha.

10. Completely destroying any place by means of fire, etc.

11. Teaching shunyata to those who are not yet ready.

12. Turning people away from working for full enlightenment.

13. Encouraging people to abandon their vows of moral conduct.

14. Causing others to hold distorted views about Hinayana teachings.

15. Practicing, supporting, or teaching the Dharma for financial profit and fame while saying that your motives are pure, and that only others are pursuing Dharma for such base aims.

16. Telling others even though you have very little or no understanding of shunyata, that you have profound understanding of shunyata.

17. Taking gifts from others and encouraging others to give you things originally intended as offerings to the Three Jewels.

18. Taking away from those monks who are practicing meditation and giving it to those who are merely reciting texts.

Lama Lhundrup: This is not very good—there are things missing. Are there eighteen now?

[Further discussion]

Lama Lhundrup: Most are okay, most are correct. Right? These are the eighteen root downfalls. If you observe these eighteen root vows purely, then the forty-six auxiliary vows are already included in these root eighteen vows.

The Four Conditions

There are four main conditions that have to be fulfilled in order to incur the complete transgression of a root vow. The first of these conditions is having broken a vow before and still wishing to break it in the future. Secondly, we are not able to abandon that downfall and we wish to pursue the downfall again. Thirdly, we feel very happy to break the vow and we don’t see any faults or disadvantages to our actions. Lastly, we don’t have any sense of shame or consideration for others. If these four points are present, there is complete transgression of the root vow.

We explained these eighteen root downfalls very briefly, but if we explain them elaborately, each vow branches out into many, many different points.

Two of these eighteen vows do not require the fulfillment of all four conditions in order to incur the full transgression. These two vows are giving up bodhicitta and the generation of wrong views. These two vows do not require all four conditions to be present for complete transgression. The moment you give up or totally disregard bodhicitta, that naturally causes the root downfall, without the presence of any of the four conditions. Also, the generation of wrong views is powerful enough to cut off the continuum of virtue. So, these two vows do not require the presence of the four conditions, but the remaining sixteen require the presence of all four conditions in order to incur the full downfall. If all four conditions are not present, we incur only the shortcoming of breaking that particular vow.

Of these four conditions, if we have one point that says if we don’t see the fault or the harm in that transgression, we have a medium level of contamination. Literally it’s called “medium contamination,” and we have only a partial transgression as opposed to a full transgression.

If we engage in one of these root downfalls and we see the faults or the shortcomings of undertaking that course of action, we incur only a small contamination. If we have this particular condition but do not have the other three conditions, by being aware of the fault in this action, it becomes only a small shortcoming. Having understood these eighteen root downfalls, because they can be so easily accrued, if we constantly familiarize ourselves with the shortcomings, then it helps us to avoid engaging in them so easily.

The fourth condition—having a sense of shame or consideration for others—refers to the fact that if we engage in a particular transgression, we will experience the expected, ripening result, and having that awareness, we try to abstain from that negative action. That is having a sense of shame. Also, if we have consideration for others in the sense that if we engage in a particular negative action, then others will come to know of it and the Buddha will know of it. We abstain from the negative act out of consideration for others. These two points are essential for practicing Dharma. If we have a strong sense of shame and consideration for others, then we do not easily incur the transgression of vows. So, it is essential that we observe this sense of shame and consideration.

Do you have any doubts or questions about these points?

[Inaudible comment]

Lama Lhundrup: Yes, it is very easy. When we study and meditate on the graduated path to enlightenment, the first and foremost point is renunciation, in order to realize the shortcomings of cyclic existence. If we are attached to our possessions or the pleasures of this life, there is no way to generate renunciation, and if we do not have renunciation, there is no way to generate compassion, and without compassion there's no bodhicitta.

Okay, you can use for others. Your motivation is for others, not for your selfish motivation but for others. Eating chocolate “I eat for beneficial all mother sentient beings.” All right? Okay? So then for the whole day if you want chocolate, you have no problem. All right? Yes, it depends on your mind. It looks easy. If you have control of your mind, then okay. Right? Simple.

Student: What happens when vows overlap? For example, walking up to Kopan Hill, many people ask me for one rupee, but the rupees in my pocket are to study the Dharma. How does that work?

Lama Lhundrup: I think, okay.

Student: Which one? To give the rupee or to buy the lessons of Dharma?

Lama Lhundrup: Maybe you can first buy lessons for the Dharma, then later you can give to the world. All right.

Student: So there is a priority?

Lama Lhundrup: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Otherwise, you cannot get opportunity to listen to Dharma. All right?

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: Yes, that’s you can see, nuclear, atom bomb.

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: Because we have a strong selfish mind. We still have the vows, but there is also that strong selfish mind. So when somebody is destroying, disturbing us and doing very bad things to us, so then we get very angry. So then anger makes us want to do many incredible, bad things. We cannot control ourselves.

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: Some beginning ordinary being can take these kind of vows, yes, no problem. Yes, they can take.

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: Military, army? Possible. Some people first take the vows, then somebody puts them in the army, but they can do like that.

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: If by telling the truth, then you destroy the other person, then maybe you can somehow change the words. The bodhisattva can do this kind of lying, if it is really beneficial. They can tell a lie if it is beneficial for them. With a motivation of compassion we can lie. Otherwise, when we lie we destroy their own peace. Yes, by our motivation, motivation is very important, all right? So then okay, you can say.

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: You can say this, but after you have conception, Oh, I told Mum lying, so then after night time you have purification. All right?

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: You can try to just have the motivation, to try never to kill any sentient beings. “I don't kill animals”, you just have that motivation, you can say like this. So it doesn’t matter if you can just have this kind of motivation, then if you [accidentally] kill an animal, you don't have the motivation for killing. But if you see a dead animal then you can do something for them such as saying OM MANI PADME HUM. Whatever you do for them is beneficial.

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: If you took bodhisattva vows then you can do sessions for whole your life, you become the Mahayana path, yes. This is more comfortable.

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: That’s difficult. What example you can tell me? Why giving back? Reasons?

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: That kind if you have some good reasons, then you can ask guru and if guru says okay, then you have. Yes.

Student: [inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: Root or what? Maybe you can say what.

Student: [inaudible]

[Inaudible discussion]

Lama Lhundrup: If we have a strong bodhicitta motivation, then these seven nonvirtuous actions of the body and speech2 are allowed in the case of bodhisattvas, who have bodhicitta. They have an exemption over these nonvirtuous actions depending on the circumstances. In this case, we are talking about people who have spontaneous, genuine, intuitive bodhicitta. They have exemption from these seven nonvirtues of body and speech. We are not talking about somebody who just has it verbally or by making effort. It is not an exemption for those who do not have bodhicitta; it is an exemption for those who have bodhicitta. These people are allowed to do these actions under circumstances that will give the most benefit. In our undertaking of a particular nonvirtuous action, we should feel completely tolerant of any result that we might incur.

[Question inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: There's no harm in that particular one because there is no truly existent Christianity and therefore we can see Christianity and Buddhism as oneness in nature, because the essential point of Buddhism is non-violence, or not giving harm. That is the essential point. It is concordant with Christian philosophy and it is the main point of Buddhism too. So we abide in that nature, in that point.

[Question inaudible]

Lama Lhundrup: If we have a teaching from Christian teachers and it is a way of developing ourselves and developing our bodhicitta, then we can still practice it. If, instead of developing us, it undermines us and degenerates our mind, then we have the wisdom to differentiate.

Student: So, the very broad meaning of practice is simply practicing bodhicitta, practicing to develop your mind? That’s all?

Lama Lhundrup: Yes, true mind, true bodhicitta, true love, that's all. Thank you. Okay, thank you very much.

Notes

1 See also the Bodhisattva Vows, available from FPMT Foundation Store. [Return to text]

2 The seven nonvirtues of body and speech (of the ten nonvirtues) are: killing, stealing, sexual misconduct, lying, speaking harsh words, slandering and gossiping. [Return to text]

First Discourse: Dharma, Samsara, and Q&A

First Discourse: Dharma, Samsara, and Q&A

Before giving the actual teaching Rinpoche would like to say some prayers. First is a prayer to Shakyamuni Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, and this prayer contains prostration, recitation of Sutra and dedication. The second prayer is The Hundred Deities of Tushita because Rinpoche is here to represent the Gelugpa tradition. The next prayer will be

Before giving the actual teaching Rinpoche would like to say some prayers. First is a prayer to Shakyamuni Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, and this prayer contains prostration, recitation of Sutra and dedication. The second prayer is The Hundred Deities of Tushita because Rinpoche is here to represent the Gelugpa tradition. The next prayer will be

Searching for happiness

Searching for happiness The wisdom and form bodies of a buddha

The wisdom and form bodies of a buddha

The ultimate purpose of listening to teachings is to receive enlightenment. Therefore, before listening to [or reading] this teaching on the Foundation of All Good Qualities [Tib: Yön-ten-shir-gyur-ma], it is necessary to cultivate the pure thought of bodhicitta, the main cause of enlightenment.

The ultimate purpose of listening to teachings is to receive enlightenment. Therefore, before listening to [or reading] this teaching on the Foundation of All Good Qualities [Tib: Yön-ten-shir-gyur-ma], it is necessary to cultivate the pure thought of bodhicitta, the main cause of enlightenment.