| Mirror of Wisdom includes commentaries on the emptiness section of Mind Training Like the Rays of the Sun and The Heart Sutra. |

CHAPTERS

Mirror of Wisdom

Part One: Introduction

Part One: Mind Training - Developing Bodhicitta

Part One: Mind Training - Developing Emptiness

Part One: Learning to Become a Buddha

Part Two: Commentary on the Heart Sutra

PRELIMINARIES

We should always begin our study and practice at the basic level and slowly ascend the ladder of practice. First of all, we should learn about going for refuge in the Three Jewels of Buddha, Dharma and Sangha and put that into practice. Then we should study and follow the law of karmic actions and their results. Next, we should meditate on the preciousness of our human life, our great spiritual potential and upon our own death and the impermanence of our body. After that we should develop an awareness of our own state of mind and notice what it is really doing. If we are thinking of harming anyone, even the smallest insect, then we must let go of that thought, but if our mind is thinking of something positive, such as wishing to help and cherish others, then we must try to enhance that quality. As we progress, we slowly train our mind in bodhicitta and go on to study the perfect view of emptiness. This is the proper way to approach Buddhist study and practice.

As we engage in our practice of Dharma there will be definite signs of improvement. Of course, these signs should come from within. The great Kadampa master, Geshe Chekawa, states, "Change or transform your attitude and leave your external conduct as it is." What he is telling us is that we should direct our attention towards bringing about positive transformation within, but in terms of our external conduct we should still behave without pretense, like a normal person. We should not be showy about any realization we have gained or think that we have license to conduct ourselves in any way we like. As we look into our own mind, if we find that delusions such as anger, attachment, arrogance and jealousy are diminishing and feel more intent on helping others, that is a sign that positive change is taking place.

Lama Tsongkhapa stated that in order to get rid of our confusion with regard to any subject, we must develop the three wisdoms that arise through contemplation. We have to listen to the relevant teaching, which develops the "wisdom through hearing." Then we contemplate the meaning of the teaching, which gives rise to the "wisdom of contemplation." Finally, we meditate on the ascertained meaning of the teaching, which gives rise to the "wisdom of meditation." By applying these three kinds of wisdom, we will be able to get beyond our doubts, misconceptions and confusion.

INVESTIGATING OUR ACTIONS

The text advises that we should apply ourselves to gross analysis (conceptual investigation) and subtle analysis (analytical investigation) to find out if we are performing proper actions with our body, speech and mind. If we are, then there is nothing more to do. However, if we find that certain actions of our body, speech and mind are improper, we should correct ourselves.

Every action that we perform has a motivation at its beginning. We have to investigate and analyze whether this motivation is positive or negative. If we discover that we have a negative motivation, we have to let go of that and adopt a positive one. Then, while we're actually performing the action, we have to investigate whether our action is correct or not. Finally, once we have completed the action, we have to end it with a dedication and again, analyze the correctness of our dedication. In this way, we observe the three phases of our every action of body, speech and mind, letting go of the incorrect actions and adopting the correct ones.

We should do this as often as we can, but we should try to do it at least three times a day. First thing in the morning, when we get up from our beds, we should analyze our mind and set up the right motivation for the day. During the day we should again apply this mindfulness to our actions and activities. Then in the evening, before we go to bed, we should review our actions of the daytime. If we find that we did something that we shouldn't have, we should regret the wrong action and develop contrition for having engaged in it and determine not to engage in that action again. It is essential that we purify our negativities, or wrong actions, in this way. However, if we find that we have committed good actions, we should feel happy. We should appreciate our own positive actions and draw inspiration from them, determining that tomorrow we should try to do the same or even better.

Buddha said, "Taking your own body as an example, do not harm others." So, taking ourselves as an example, what do we want? We want real peace, happiness and the best of everything. What do we not want? We don't want any kind of pain, problem or difficulty. Everyone else has the same wish-so, with that kind of understanding we should stop harming others, including those who we see as our enemies. His Holiness the Dalai Lama often advises that if we can't help others, then we should at least not harm them, either through our speech or our physical actions. In fact, we shouldn't even think harmful thoughts.

PRACTICING PATIENCE

The text states that we should not be boastful. Instead, we should appreciate the good actions we've performed. If you go up to people and say, "Haven't I been kind to you?" nobody will appreciate what you've done. In the Eight Verses of Mind Training, we read that even if people turn out to be ungrateful to us and say or do nasty things when we have been kind and helpful to them, we should make all the more effort to appreciate the great opportunity they have provided us to develop our patience. The stanza ends beautifully, "Bless me to be able to see them as if they were my true teachers of patience." After all, they are providing us with a real chance to practice patience, not just a hypothetical one. That is exactly what mind training is. When we find ourselves in that kind of difficult situation, we should just stay cool and realize that we have a great opportunity to practice kshantiparamita, the "perfection of patience."

In the same vein, the text also advises us not to be short-tempered. We shouldn't let ourselves be shaken by difficult circumstances or situations. Generally, when people say nice things to us or bring us gifts, we feel happy. On the other hand, if someone says the smallest thing that we don't want to hear, we get upset. Don't be like that. We need to remain firm in our practice and maintain our peace of mind.

DEVELOPING CONSISTENCY

The text reminds us to practice our mind training with consistency. We shouldn't practice for a few days and then give it up because we've decided it's not working. At first, we may apply ourselves very diligently to study and practice out of a sense of novelty or because we've heard so much about the benefits of meditation. Then, in a day or two, we stop because we don't think we're making any progress. Or, for a while we may come to the teachings before everyone else but then we just give up and disappear, making all kinds of reasons and excuses for our behavior. That won't help.

If we keep in mind that our ultimate goal is to become completely enlightened, then we can begin to comprehend the length of time we'll need for practice. The great Indian master, Chandrakirti, says that all kinds of accomplishments follow from diligence, consistency and enthusiasm. If we apply ourselves correctly to the proper practice we will eventually reach our destination. He says that if we don't have constant enthusiasm, even if we are very intelligent we are not going to achieve very much. Intelligence is like a drawing made on water but constant enthusiasm in our practice is like a carving made in rock-it remains for a much longer time.

So, whatever practice each of us does, big or small, if we do it consistently, over the course of time we will find great progress within ourselves. One of the examples used in Buddhist literature is that our enthusiasm should be constant, like the flow of a river. Another example compares consistency to a strong bowstring. If a bowstring is straight and strong, we can shoot the arrow further. We read in a text called The Praise of the Praiseworthy, "For you to prove your superiority, show neither flexibility nor rigidity." The point being made here is that we should be moderate in applying ourselves to our practice. We should not rigidly overexert ourselves for a short duration and then stop completely, but neither should we be too flexible and relaxed, because then we become too lethargic.

EXPECTATIONS OF REWARD

The next advice given in the text is that we should not anticipate some reward as soon as we do something nice. When we practice giving, or generosity, the best way to give is selflessly and unconditionally. That is great giving. In Buddhist scriptures we find it stated that as a result of our own giving and generosity, we acquire the possessions and resources we need. When we give without expecting anything in return, our giving will certainly bring its result, but when we give with the gaining of resources as our motivation, our giving becomes somewhat impure. Intellectualizing, thinking, "I must give because giving will bring something back to me," contaminates our practice of generosity.

When we give we should do so out of compassion and understanding. We have compassion for the poor and needy, for example, because we can clearly see their need. Sometimes people stop giving to the homeless because they think that they might go to a bar and get drunk or otherwise use the gift unwisely. We should remember that when we give to others, we never have any control over how the recipient uses our gift. Once we have given something, it has become the property of the other person. It's up to them to decide what they will do with it.

KARMIC ACTIONS

Another cardinal point of Buddhism concerns karmic actions. Sometimes we go through good times in our lives and sometimes we go through bad; but we should understand that all these situations are related to our own personal karmic actions of body, speech and mind. Shakyamuni Buddha taught numerous things intended to benefit three kinds of disciples-those who are inclined to the Hearers' Vehicle, those who are inclined to the Solitary Realizers' Vehicle and those who are inclined to the Greater Vehicle. Buddha said to all three kinds of prospective disciples, "You are your own protector." In other words, if you want to be free from any kind of suffering, it is your own responsibility to find the way and to follow it. Others cannot do it for you. No one can present the way to liberation as if it were a gift. You are totally responsible for yourself.

"You are your own protector." That statement is very profound and carries a deep message for us. It also implicitly speaks about the law of karmic actions and results. You are responsible for your karmic actions-if you do good, you will have good; if you do bad, you will have bad. It's as simple as that. If you don't create and accumulate a karmic action, you will never meet its results. Also, the karmic actions that you have already created and accumulated are not simply going to disappear. It is just a matter of time and the coming together of certain conditions for these karmic actions to bring forth their results. When we directly, or non-conceptually, fully realize emptiness, from that moment on we will never create any new karmic seeds to be reborn in cyclic existence. It is true that transcendent bodhisattvas return to samsara, but they don't come back under the influence of contaminated karmic actions or delusions. They return out of their will power, their aspirational prayers and their great compassion.

THE DESIRE TO BE LIBERATED

Without the sincere desire to be free from cyclic existence, it is impossible to become liberated from it. In order to practice with enthusiasm, we must cultivate the determined wish to be liberated from the miseries of cyclic existence. We can develop this enthusiastic wish by contemplating the suffering nature of samsara, this cycle of compulsive rebirths in which we find ourselves. As Lama Tsongkhapa states in his beautifully concise text, theThree Principal Paths, without the pure, determined wish to be liberated, one will not be able to let go of the prosperity and goodness of cyclic existence. What he is saying-and our own experience will confirm this-is that we tend to focus mostly, and perhaps most sincerely, on the temporary pleasures and happiness of this lifetime. As we do this, we get more and more entrenched in cyclic existence.

In order to break this bond to samsara, it is imperative that we cultivate the determined wish for liberation, and to do that we have to follow certain steps. First, we must try to sever our attachment and clinging to the temporary marvels and prosperity of this lifetime. Then we need to do the same thing with regard to our future lives. No matter whether we are seeking personal liberation or complete enlightenment for the benefit of all sentient beings, we must first cultivate this attitude of renunciation. Having done that, if we want to find our own personal liberation, or nirvana, then we can follow the path of hearers or solitary realizers, but if we want to work for the betterment of all sentient beings, we should at that point follow Greater Vehicle Buddhism-the path of the bodhisattvas-which leads to the highest state of enlightenment.

The determined wish to be liberated is the first path of Lama Tsongkhapa's Three Principal Paths, which presents the complete path to enlightenment. Tsongkhapa said that this human life, with its freedoms and enriching factors, is more precious than a wish-fulfilling gem. He also tells us that, however valuable and filled with potential our life is, it is as transient as lightning. We must understand that worldly activities are as frivolous and meaningless as husks of grain. Discarding them, we should engage instead in spiritual practice to derive the essence of this wonderful human existence. We need to realize the preciousness and rarity of this human life and our great spiritual potential as well as our life's temporary nature and the impermanence of all things. However, we should not interpret this teaching as meaning that we should devalue ourselves. It simply means that we should release our attachment and clinging to this life because they are the main source of our problems and difficulties. We also need to release our attachment and clinging to our future lives and their particular marvels and pleasures. As a way of dealing with this attachment, we need to contemplate and develop conviction in the infallibility of the law of karmic actions and their results and then contemplate the suffering nature of cyclic existence.

How do we know when we have developed the determined wish to be liberated? Lama Tsongkhapa says that if we do not aspire to the pleasures of cyclic existence for even a moment but instead, day in and day out, find ourselves naturally seeking liberation, then we can say that we have developed the determined wish to be liberated. If we were to fall into a blazing fire pit, we wouldn't find even one moment that we wanted to be there. There'd be nothing enjoyable about it at all and we would want to get out immediately. If we develop that kind of determination regarding cyclic existence, then that is a profound realization. Without even the aspiration to develop renunciation, we will never begin to seek enlightenment and therefore will not engage in the practices that lead us towards it.

MOTIVATION FOR SEEKING ENLIGHTENMENT

There are three kinds of motivation we can have for aspiring to attain freedom from the sufferings of cyclic existence. The lowest motivation seeks a favorable rebirth in our next life, such as the one we have right now. With this motivation we will be able to derive the smallest essence from our human life.

The intermediate level of motivation desires complete liberation from samsara and is generating by reflecting upon the suffering nature of cyclic existence and becoming frightened of all its pains and problems. The method that can help us attain this state of liberation is the study of the common paths of the Tripitaka, the Three Baskets of teachings, and the practice and cultivation of the common paths of the three higher trainings-ethics, concentration and wisdom. This involves meditating on emptiness and developing the wisdom that realizes emptiness as the ultimate nature of all phenomena. As a result of these practices, we are then able to counteract and get rid of all 84,000 delusions and reach the state of liberation. With this intermediate motivation we achieve the state of lasting peace and happiness for ourselves alone. Our spiritual destination is personal nirvana. The highest level of motivation is the altruistic motivation of bodhicitta -seeking complete enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings. With this kind of motivation, we are affirming the connections we have made with all sentient beings over many lifetimes. All sentient beings are recognized as having once been our mothers, fathers and closest friends. We appreciate how kind they have been to us and we develop the responsibility of helping them to become free from all their suffering and to experience lasting peace and happiness. When we consider our present situation we see that at the moment, we don't actually have the power to do this but once we have become fully enlightened beings, we will have all kinds of abilities to help sentient beings get rid of their pains and problems and find peace and happiness.

THE SUFFERING NATURE OF SAMSARA

If we reflect on the situation in which we find ourselves, we will realize that with so much unbearable pain and suffering, it is as though we were in a giant prison. This is the prison of cyclic existence. However, because of our distorted perception, we often see this prison as a very beautiful place; as if it were, in fact, a wonderful garden of joy. We don't really see what the disadvantages of samsara are, and because of this we find ourselves clinging to this existence. With this attachment, we continue creating karmic actions that precipitate our rebirth in it over and over again and thus keep us stuck in samsara. If we look deep within ourselves, we find that it is the innate grasping at self that distorts our perception and makes us see cyclic existence as a pleasure land. All of us who are trapped in samsara share that kind of distorted perception, and as a result, we find ourselves creating all sorts of karmic actions. Even our good karmic actions are somewhat geared towards keeping us imprisoned within cyclic existence.

We should try to understand that being in cyclic existence is like being in a fire pit, with all the pain that such a situation would bring. When we understand this, we will start to change the nature of our karmic actions. Buddha said this in the sutras and Indian masters have carried this teaching over into the commentaries, or shastras. No matter where we live in samsara, we are bound to experience suffering. It doesn't matter with whom we live-our friends, family and companions all bring problems and suffering. Nor does it matter what kind of resources we have available to us; they too ultimately bring us pain and difficulty.

Now, you might think, "Well, that doesn't seem to be altogether true. In this world there are many wonderful places to visit-magnificent waterfalls, lovely wildernesses and so on. It doesn't seem as if samsara is such a bad place to be. Also, I have many wonderful friends who really care for me. It doesn't seem true that those in cyclic existence to whom I am close bring me problems and sufferings. Moreover, I have delicious food to eat and beautiful things to wear, so neither does it seem that everything I use in cyclic existence is suffering in nature." If such are our thoughts and feelings, then we have not realized the true nature of samsara, which is actually nothing but misery. Let me explain more about how things really are in samsara. The first thing the Buddha spoke about after his enlightenment was the truth of suffering. There are three kinds of pains and problems in cyclic existence-the "suffering of misery," the "suffering of change" and "pervasive suffering." We can easily relate to the suffering of misery, as this includes directly manifested pain and problems, such as the pain we experience if we cut ourselves or get a headache. However, our understanding of suffering is usually limited to that. We don't generally perceive the misery of change, which is a subtler kind of suffering. Even when we experience some temporary pleasures and comforts in cyclic existence, we must understand that these things also change into pains and problems. Pervasive, or extensive, suffering is even more subtle and hence even more difficult for us to understand. Suffering is simply the nature of samsara. When we have a headache we take medicine for the pain or when there is a cut on our body we go to the doctor for treatment, but we generally don't seek treatment for the other two kinds of suffering.

Buddhas and bodhisattvas feel infinite compassion for those of us who are trapped within cyclic existence because we don't realize that our pain and suffering are our own creation. It is as though we are engaged in self-torture. Our suffering is due to our own negative karmic actions, which in turn are motivated by all sorts of deluded thoughts and afflictive emotions. Just as we would feel compassion for a close friend who had gone insane, so are the buddhas and bodhisattvas constantly looking for ways in which to help us free ourselves from these problematic situations. With their infinite love and compassion, they are always looking for ways to assist us in getting out of this messy existence.

None of us would like to be a slave. Slaves go through all kinds of altercations, restrictions and difficulties and try with all their might to find freedom from their oppressors. Likewise, we have become slaves to the oppressors of our own delusions and afflictive emotions. These masters have enslaved us not only in this lifetime but for innumerable lifetimes past. As a result, we have gone through countless pains and sufferings in cyclic existence. Obviously, if we don't want to suffer such bondage any longer, we need to make an effort at the first given opportunity to try to free ourselves. In order to do this, we need to cultivate the wisdom realizing selflessness, or emptiness. In Sanskrit, the word is shunyata, ortathata, which is translated as "emptiness," or "suchness." This wisdom is the only tool that can help us to destroy the master of delusions-our self-grasping ignorance. Emptiness is the ultimate nature of all that exists. As such it is the antidote with which we can counteract all forms of delusion, including the root delusions of ignorance, attachment and anger.

THE SELF-CHERISHING ATTITUDE

Buddha has stated that for Mahayana practitioners, the self-cherishing attitude is like poison, whereas the altruistic, other-cherishing attitude is like a wish-fulfilling gem. Self-centeredness is akin to a toxic substance that we have to get out of our system in order to find the jewel-like thought of cherishing other beings. When we ingest poison it contaminates our body and threatens our very existence. In the same way, the self-cherishing attitude ruins our chance to improve our mind. With it, we destroy the possibility for enlightenment and become harmful to others. By contrast, if we have the mental attitude of cherishing other beings, not only will we be able to find happiness and the best of everything we are seeking, but we will also be able to bring goodness to others.

In order to cultivate the altruistic attitude, we should reflect on the kindness of all other beings. As we learn to appreciate their kindness we also learn to care for them. We might accept the general notion that sentient beings must be cherished, but when we come down to it we find ourselves thinking, "Well, so and so doesn't count because they have been mean or unpleasant to me, so I'll take them off the list and just help the rest." If we do that we are missing the whole point and are limiting our thinking. We need all other beings in order to follow the path that Buddha has shown us.

It is others who provide us with the real opportunities to grow spiritually. In fact, in terms of providing us with the actual opportunities to follow the path leading to enlightenment, sentient beings are just as kind to us as are the buddhas. To use a previous example in a different context, in order to grow any kind of fruit tree we need its seed. However, it's not enough just to have the seed-we also need good fertile soil, otherwise the seed won't germinate. So, although Buddha has given us the seed-the path to enlightenment-sentient beings constitute the field of our growth-the opportunities to actually engage in activities leading to the state of enlightenment.

PRACTICES FOR DEVELOPING BODHICITTA

There are two methods of instruction for developing bodhicitta. The first is the "six causes and one result," which has come down to us through a line of transmission from Shakyamuni Buddha to Maitreya and Asanga and his disciples. The second is called "equalizing and exchanging self for others," an instruction that has come down to us from Shakyamuni Buddha to Manjushri and Arya Nagarjuna and his disciples. It doesn't matter which of these two core instructions for developing bodhicitta we put into practice. The focal object of great compassion is all sentient beings and its aspect is wishing them to be free from every kind of pain and suffering.

We start at a very basic level. We try to cultivate compassion towards our family members and friends, then slowly extend our compassion to include people in our neighborhood, in the same country, on the same continent and throughout the whole world. Ultimately, we include within the scope of our compassion not only all people but all other beings throughout the universe. We find that we cannot cause harm to any sentient being because this goes against our compassion.

Before generating such compassion, however, we need to cultivate even-mindedness-a sense of equanimity towards others-because our compassion has to extend equally towards all sentient beings, without discrimination. Usually, we divide people mentally into different categories. We have enemies on one side, friends and relatives on another and strangers somewhere else. We react differently towards each group. We have very strong negative feelings towards our enemies-we put them way away from us and if anything bad happens to them we feel a certain satisfaction. We have an indifferent attitude towards those who are strangers-we don't care if bad or good things happen to them because to us, they don't count. But if anything happens to those near and dear to us, we are immediately affected and experience all kinds of feelings in response.

In order to balance our attitude towards people and other beings, we should understand that there is nothing fixed in terms of relationships between ourselves and others. Someone we now see as a very dear friend could become our worst enemy later on in this life or the next. Similarly, someone we regard as an enemy could become our best friend. When we take rebirth our relationships change. We may become someone of a different race or some kind of animal. There is so much uncertainty in this changing pattern of lives and futures. As we take this into consideration, we begin to realize that there's no sense in discriminating between friends and enemies. In the light of all this change we should understand that all beings should be treated equally.

As we train our minds in this way, the time will come when we feel as close to all sentient beings as we currently feel to our dearest relatives and friends. After balancing our attitude in regard to people and other beings, we will easily be able to cultivate great compassion. However, we should not confuse compassion with attachment. Some people, motivated by attachment to their own skill in helping or to the outcome of their assistance, become very close and helpful to others and think that this is compassion, but it is not. Great compassion is a quality that someone who hasn't yet entered the path of Mahayana could have. So, after cultivating compassion and bodhicitta, you should combine it with cultivating the wisdom that understands emptiness. This is known as "integrating method and wisdom" and is essential to reach the state of highest enlightenment.

I always qualify personal nirvana to differentiate it from enlightenment. In the higher practices, Theravadins cultivate a path that brings them to the state of nirvana, or liberation. These are people who are seeking personal freedom from cyclic existence. They talk about "liberation with remainder"-liberation that is attained while one still has the aggregates, the contaminated body and mind. "Liberation without remainder" means that one discards the body and then achieves the state of liberation. To attain the highest goal within the tradition of Theravada Buddhism, one has to observe pure ethics, study or listen to teachings on the practice, contemplate the teachings and then meditate on them. For those of us who are following the Mahayana tradition, however, our intention should be to do this work of enlightenment for the benefit and sake of all other sentient beings. In Mahayana Buddhist practice we also need to follow the same four steps, but we are not so much seeking our own personal goal as we are aspiring to become enlightened beings in order to be in a position to help others.

READINESS FOR RECEIVING EMPTINESS TEACHINGS

Mahayana Buddhism consists of two major categories or vehicles. The first is the Sutrayana, the Perfection Vehicle; the second is the Tantrayana, the Vajra Vehicle. In order for anyone to practice tantric Buddhism, he or she should be well prepared and should have become a suitable vessel for such teachings and practices. Sutrayana is more like an open teaching for everyone. However, there are exceptions to this rule.

Even within the Sutra Vehicle, the emptiness teachings should not be given to just anyone who asks but to only suitable recipients- those who have trained their minds to a certain point of maturity. Then, when the teachings on emptiness are given, they become truly beneficial to that person. Let's say that we have the seed of a very beautiful flower that we wish to grow. If we simply dump the seed into dry soil it is not going to germinate. This doesn't mean that there is something wrong with the seed. It's just that it requires other causes and conditions, such as fertile soil, depth and moisture in order to develop into a flower. In the same way, if a teaching on emptiness is given to someone whose mind is not matured or well-enough trained, instead of benefiting that person it could actually give them harm.

There was once a great Indian master named Drubchen Langkopa. The king of the region where he lived heard about this master and invited him to his court to give spiritual teachings. When Drubchen Langkopa responded to the king's request and gave a teaching on emptiness, the king went berserk. Although the master didn't say anything that was incorrect, the king completely misunderstood what was being taught because he wasn't spiritually prepared for it. He thought that the master was telling him that nothing existed at all. In his confusion, he decided that Drubchen Langkopa was a misleading guide and had him executed. Later on, another master was invited to the court. He gradually prepared the king for teachings on emptiness by first talking about the infallibility of the workings of the law of karmic actions and results, impermanence and so on. Finally, the king was ready to learn about emptiness as the ultimate reality and at last understood what it meant. Then he realized what a great mistake he had made in ordering the execution of the previous master.

This story tells us two things. Firstly, the teacher has to be very skillful and possess profound insight in order to teach emptiness to others. He or she needs two qualities known as "skillful means" and "wisdom." Secondly, the student needs to be ready to receive this teaching. The view of emptiness is extremely profound and is therefore hard to grasp. There are two aspects of emptiness, or selflessness -the emptiness, or selflessness, of the person and the emptiness, or selflessness, of phenomena.

People who are unprepared get scared that the teachings are actually denying the existence of everything. It sounds to them as if the teachings are rejecting the entire existence of phenomena. They don't understand that the term "emptiness" refers to the emptiness of inherent, or true, existence. They then take this misunderstanding and apply it to their own actions. They come to the conclusion that karmic actions and their results don't really exist at all and become wild and crazy, thinking that whatever makes their lives pleasurable or humorous is okay because their actions have no consequences.

Additionally, the listener's sense of ego can also become an obstacle, as the idea of emptiness can really frighten those who are not ready for it to the extent that they abandon their meditation on emptiness altogether. Buddha's teaching on emptiness is a core, or inner essence, teaching, and if for some reason we abandon it, this becomes a huge obstacle to our spiritual development. It is very important to remember that discovering the emptiness of any phenomenon is not the same as concluding that that phenomenon does not exist at all.

In his Supplement to the Middle Way, Chandrakirti describes indicative signs by which one can judge when someone is ready to learn about emptiness. He explains that just as we can assume that there is a fire because we can see smoke or that there is water because we can see water birds hovering above the land, in the same way, through certain external signs, we can infer that someone is ready to receive teachings on emptiness. Chandrakirti goes on to tell us, "When an ordinary being, on hearing about emptiness, feels great joy arising repeatedly within him and due to such joy, tears moisten his eye and the hair on his body stands up, that person has in his mind the seed for understanding emptiness and is a fit vessel to receive teachings on it."

If we feel an affinity for the teachings and are drawn towards them, it shows that we are ready. Of the external and internal signs, the internal are more important. However, if we don't have these signs, we should make strong efforts to make ourselves suitable vessels for teachings on emptiness. To do so, we need to do two things- accumulate positive energy and wisdom and purify our deluded, negative states of mind. For the sake of simplicity, we refer to these as the practices of accumulationand purification.

In order to achieve the two types of accumulation-the accumulation of merit, or positive energy, and the accumulation of insight, or wisdom -we can engage in the practice of the six perfections of generosity, ethics, patience, enthusiastic perseverance, concentration and wisdom. Through such practices we will be able to accumulate the merit and wisdom required for spiritual progress.

We can talk about three kinds of generosity (dana, in Sanskrit)- the giving of material things, the giving of Dharma and the giving of protection, or freedom from fear. The giving of material help is easily understood. In the Lam-rim chen-mo, Lama Tsongkhapa's great lam-rim text, we read that even if you have only a mouthful of food, you can practice material giving by sharing it with a really needy person. When we see homeless people on the streets, we often get irritated or frustrated by their presence. That is not a good attitude. Even if we can't give anything, we can at least wish that someday we will be in a position to help.

The giving of Dharma can be practiced by anyone, not just a lama. For example, when you do your daily practice with the wish to benefit others, there might be some divine beings or other invisible beings around you who are listening. So, when you dedicate your prayers to others, that is giving of Dharma, or spirituality. Somebody out there is listening; remember that. An example of giving protection would be saving somebody's life.

In his Supplement, Chandrakirti says, "They will always adopt pure ethics and observe them. They will give out of generosity, will cultivate compassion and will meditate on patience. Dedicating such virtue entirely to full awakening for the liberation of wandering beings, they pay respect to accomplished bodhisattvas." In Tibetan, ethics, or moral discipline, is called tsul-tim, which means "the mind of protection." Ethics is a state of mind that protects us from negativity and delusion. For example, when we vow not to kill any sentient being, we develop the state of mind that protects us from the negativity of killing.

In Buddhism, we find different kinds of ethics. On the highest level there are the tantric ethics-tantric vows and commitments. At the level below these are the bodhisattva's ethics, and below these are the ethics for individual emancipation-pratimoksha, in Sanskrit. If we want to practice Buddhism, then even if we have not taken the tantric or bodhisattva vows, there are still the ethics of the lay practitioner. And if we have not taken the lay vows, we must still observe the basic ethics of abandoning the ten negativities of body, speech and mind. Avoiding these ten negativities is the most basic practice of ethics. If anyone performs these ten actions, whether they are a Buddhist or not, they are committing a negativity.

There are three negativities of body-killing, stealing and indulging in sexual misconduct. There are four negativities of speech-lying, causing disharmony, using harsh language and indulging in idle gossip. There are three negativities of mind-harmful intent, covetousness and wrong, or distorted, views. When we develop the state of mind to protect ourselves from these negativities and thus cease to engage in them, we are practicing ethics. Furthermore, we must always try to keep purely any vows, ethics and commitments we have promised to keep.

In addition to these ten negativities there are also the five "boundless negativities," or heinous crimes. These are killing one's father, killing one's mother, killing an arhat, shedding the blood of an enlightened being-we use the term "shedding the blood" here because an enlightened being cannot be killed-and causing a schism in the spiritual community. These negativities are called "boundless" because after the death of anyone who has committed any of them, there is a very brief intermediate state followed immediately by rebirth directly into a bad migration such as the hell, hungry ghost or animal realms.

We have discussed generosity, ethics, patience and the need for enthusiasm and consistency in our practice. Regarding the remaining perfections of concentration and wisdom, even though we may not at present have a very high level of concentration, we do need to gain a certain amount of mental stability so that we don't indulge in negativities. We must also cultivate the perfection of wisdom, which understands the reality of emptiness. We may not yet have developed the wisdom that perceives emptiness as the ultimate nature of all phenomena, but we should begin by developing our "wisdom of discernment" so that we can differentiate between right and wrong actions and apply ourselves accordingly. All these things constitute the actual practice that can help us to attain good rebirths in future.

PURIFICATION

We know that if we create any kind of karmic action-good, bad or neutral-we will experience its results. However, this does not mean that we cannot do anything to avoid the results of actions that we have already committed. If we engage in the practice of purification we can avoid having to experience the result of an earlier negative action. Some people believe that they have created too many negative actions to be able to transform themselves, but that's not true. The Buddha said that there isn't any negativity, however serious or profound, that cannot be changed through the practice of purification. Experienced masters say that the one good thing about negativities is that they can be purified. If we don't purify our mind, we cannot really experience the altruistic mind of enlightenment or the wisdom realizing emptiness.

As we look within ourselves, we find that we are rich with delusions. There are three fundamental delusions-the "three poisons" of ignorance, attachment and anger-which give rise to innumerable other delusions; as many as 84,000 of them. So, we have a lot of work to do to purify all these delusions as well as the negative karmic actions that we have created through acting under the influence of deluded motivation.

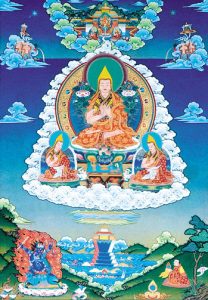

Let me tell you a true story from the life of Lama Tsongkhapa, who is believed to have been an emanation of Manjushri, the deity of wisdom. When Lama Tsongkhapa meditated on emptiness in the assembly of monks, he would become totally absorbed and simply rest in a non-dual state as if his mind and emptiness were one. After all the other monks had left the hall, Lama Tsongkhapa would still be sitting there in meditation. At times he would check his understanding of emptiness with Manjushri through the help of a mediator, a great master called Lama Umapa. Through this master, Lama Tsongkhapa once asked Manjushri, "Have I understood the view of emptiness exactly as presented by the great Indian Master, Nagarjuna?" The answer he received was "No." Manjushri advised Lama Tsongkhapa to go with a few disciples into intensive retreat and engage in purification and accumulation practices in order to deepen his understanding of emptiness.

In accordance with Manjushri's advice, Lama Tsongkhapa took eight close students, called the "eight pure disciples," and went to a place called Wölka, more than one hundred miles east of Lhasa. There, he and his students engaged in intensive purification and accumulation practices, including many preliminary practices such as full-length prostrations and recitation of the Sutra of Confession to the Thirty-five Buddhas. Lama Tsongkhapa did as many as 350,000 prostrations and made many more mandala offerings. When making this kind of offering, you rub the base of your mandala set with your forearm. Today, mandala sets are made of silver, gold or some other metal and are very smooth, but Lama Tsongkhapa used a piece of slate as his mandala base, and as a result of all his offerings wore the skin of his forearm raw.

We have a beautiful saying in Tibet: "The life-stories of past teachers are practices for posterity." So, when we hear about the lives of our lineage masters, they are not just stories but messages and lessons for us. The masters are telling us, "This is the way I practiced and went to the state beyond suffering."

During his retreat, Lama Tsongkhapa also read the great commentary to Nagarjuna's Mulamadhyamaka called Root Wisdom. Two lines of this text stood out for him-that everything that exists is characterized by emptiness and that there is no phenomenon that is not empty of inherent, or true, existence. It is said that at that very moment, Lama Tsongkhapa finally experienced direct insight into emptiness.

Some people think that emptiness isn't that difficult an insight to gain, but maybe now you can understand that it is not so easy. It is hard for many of us to sit for half an hour, even with a comfortable cushion. Those who are trained can sit for maybe forty minutes and if we manage to sit for a whole hour, we feel that it's marvelous. The great yogi Milarepa, on the other hand, did not have a cushion and sat so long that he developed calluses. This is a great teaching for us. If masters or holy beings have created any negative karmic actions, they also have to experience their results unless those actions have been purified. Even those who are nearing enlightenment still have some things to purify and need to accumulate positive energy and wisdom. If this is true even for great masters and holy beings, then it must also be true for us. We have created innumerable negative karmic actions, so we should try to purify them as much as possible. All of us-old students, new students, and myself included-need to make as much effort as we can to purify our negativities, stop creating new ones and create more positive actions. This should be our practice. Many people might be doing their best to purify the negativities they have already accumulated but feel that they are not yet ready to completely stop creating more. As a result, they naturally get involved in negativities again. This is not good. You must do your best to both purify past negativities and not create any new ones.

The practice of purification, or confession, must include the "four opponent powers," or the "four powerful antidotes." The first opponent power is the "power of contrition," or regret. If we happen to accidentally drink some poison then we really regret it because we feel so terrible. This feeling motivates us to go for treatment to detoxify our body, but we also make a kind of commitment or determination not to make that same mistake again. So, we also need to generate what is known as the "power of resolution"-the firm determination not to repeat the negativity.

The other two opponent powers are the "power of the object of reliance" and the "power of the application of antidotes." Taking refuge in the Three Jewels and generating the altruistic mind of enlightenment constitutes the power of reliance. Cultivating any general or specific meditation practice (such as meditation on the equality of self and others) constitutes the power of the application of the antidote. There is no negativity that can stand up to these four opponent powers.