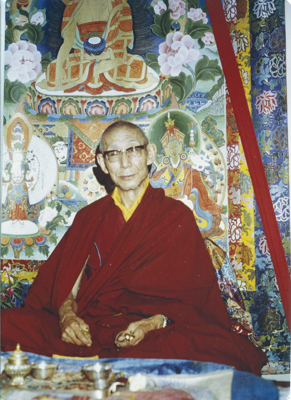

| Kyabje Trijang Rinpoche (1901-81), the late junior tutor of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, was also the root guru of Lama Yeshe, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, Geshe Rabten, Geshe Dhargyey and many other great twentieth-century teachers of the Gelug tradition. He was the main disciple of Pabongka Rinpoche and editor of Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand.

The following are excerpted from a teaching given to Western Dharma students in Dharamsala. Translated by Gavin Kilty. Prepared by Michael Lewis. Printed in From Tushita, edited and published by Michael Hellbach, Tushita Editions, 1977. Now appears in the 2005 LYWA publication Teachings From Tibet. |

The relationship between Buddhist and Hindu tantra

The relationship between Buddhist and Hindu tantra

Although some scholars have maintained that Buddhist tantra was derived from Hinduism, this is not correct. This theory, prevalent among those who adhere to the tenets of the Hinayana, is based on a superficial resemblance of various elements of the two systems, such as the forms of the deities, the meditations on psychic channels and winds, the fire rituals and so forth. Though certain practices, like the repetition of mantras, are common to both the Hindu and Buddhist tantric traditions, their interpretation—their inner meaning—is vastly different. Furthermore, Buddhist tantra is superior because, unlike Hinduism, it contains the three principal aspects of the path: renunciation, bodhicitta and the right view of emptiness.

As even animals want freedom from suffering, there are non-Buddhist practitioners who want to be free from contaminated feelings of happiness and therefore cultivate the preparatory state of the fourth meditative absorption. There are even some non-Buddhist meditators who temporarily renounce contaminated feelings of happiness and attain levels higher than the four absorptions.1 However, only Buddhists renounce all of these as well as neutral feelings and all-pervasive suffering. Then, by meditating on the sufferings together with their causes, the mental defilements, they can be abandoned forever. This explains why, even though non-Buddhists meditate on the form and formless states and attain the peak of worldly existence, they cannot abandon the mental defilements of this state. Therefore, when they meet with the right circumstances, anger and the other delusions manifest, karma is created and they remain in cyclic existence.

Because of this and similar reasons, such practices are not fit to be included in the Mahayana. They resemble neither the practices of the common sutra path [Sutrayana, or Paramitayana]—which comprises renunciation, yearning for freedom from the whole of cyclic existence; the wisdom correctly understanding emptiness, the right view, which is the antidote to ignorance, the root of cyclic existence; and bodhicitta, the mind determined to reach enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings—nor those of the exclusive Buddhist tantric path of the Great Vehicle [Vajrayana, Tantrayana, or Mantrayana].

The origin of tantra

The tantras were taught by the Buddha himself in the form of his supreme manifestation as a monk, as the great Vajradhara and in various manifestations of the central deity of specific mandalas. The great beings Manjushri, Samantabhadra, Vajrapani and others, urged by the Buddha, also taught some tantras.

In terms of the four classes of tantra, the Kriya [Action] tantras were taught by the Buddha in the form of a monk in the realm of the thirty-three gods on the summit of Mt. Meru and in the human world, where Manjushri and others were the chief hearers. The tantras requested by the bodhisattva Pungzang were taught in the realm of Vajrapani. Others were taught by the Buddha himself and, with his blessings, Avalokiteshvara, Manjushri and Vajrapani. There were also some that were spoken by worldly gods.

The Charya [Performance] tantras were taught by the Buddha in the form of his supreme manifestation in the celestial realms and in the realm called Base and Essence Adorned with Flowers.

The Yoga tantras were taught by the Buddha when he arose in the form of the central deity of each mandala in such places as the summit of Mt. Meru and in the fifth celestial realm of desire.

The Anuttara tantras were also taught by the Buddha. In the land of Ögyan, having manifested the mandala of Guhyasamaja, he taught this tantra to King Indrabodhi. The Buddha taught the Yamantaka tantras at the time of the subduing of the demonic forces, when they were requested by either the consort of Yamantaka or the consort of Kalachakra. He taught the Hevajra tantra when he arose in the form of Hevajra in the land of Madgadha at the time of destroying the four maras; it was requested by Vajragarbha and the consort of Hevajra. Having been requested by Vajrayogini, the Buddha manifested as Heruka and taught the root tantra of Heruka on the summit of Mt. Meru, and when requested by Vajrapani, taught the explanatory tantra. As for the Kalachakra tantra, which was requested by King Suchandra, a manifestation of Vajrapani, the mighty Buddha went to the glorious shrine of Dhanyakataka in south India and, manifesting the mandala of the Dharmadhatu speech surmounted by the mandala of Kalachakra, taught it there.

Although he appeared in many different manifestations, the tantras were actually taught by the enlightened teacher, Lord Buddha.

What happens during an initiation

There are many differences, some great and some small, in the initiations of each of the four classes of tantra. Therefore, one initiation is not sufficient for all mandalas. When receiving an initiation from a qualified master, certain fortunate and qualified disciples develop the wisdom of the initiation in their mind streams. Otherwise, sitting in on an initiation, experiencing the vase, water and other initiations, will plant imprints to listen to Dharma in your mind but not much else will happen. Still, you need an initiation if you want to study tantra. If the secrets of tantra are explained to somebody who has not received an initiation, the guru commits the seventh tantric root downfall and the explanation is of no benefit whatsoever to the disciple.

The relationship between sutra and tantra

Regarding renunciation and bodhicitta, there is no difference between Sutrayana and Tantrayana, but regarding conduct there is. Three kinds of conduct have been taught: disciples who admire and have faith in the Hinayana should separate themselves from all desires; disciples who admire the Sutrayana should traverse the stages and practice the perfections; those who admire the deep teachings of the Tantrayana should work with the conduct of the path of desire.

From the point of view of the philosophy, there is no difference in emptiness as an object of cognition but there is a difference in the method of its realization. In the sutra tradition, the conscious mind engages in meditative equipoise on emptiness; in tantra, the innate wisdom, an extremely subtle mind, is involved—the difference, therefore, is great. The main practice of Sutrayana, engaging in the path as a cause to achieve the form and wisdom bodies of a buddha, is the accumulation of wisdom and merit for three countless eons and the accomplishment of one’s own buddha fields. Therefore, Sutrayana is known as the causal vehicle.

In tantra, even when still a beginner, one concentrates and meditates on the four complete purities that are similar to the result—the completely pure body, pure realm, pure possessions and pure deeds of an enlightened being. Thus, tantra is known as the resultant vehicle.

The four traditions

With respect to sutra, the explanation of the Hinayana and Mahayana is the same in all the four great traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. Also, as far as the preliminary practices are concerned, there are no differences apart from the names. In the Gelug tradition they are called “the stages of the path of the three scopes”; in the Kagyü they are known as “the four ways to change the mind”; in the Drigung Kagyü as “the four Dharmas of Dagpa and the five of Drigung”; and the Sakya refer to “separation from the four attachments.” [Kyabje Rinpoche did not refer to the Nyingma tradition here.]

With respect to tantra, the individual master’s way of leading the disciples on the path depends on his experience and the instructions of the root texts and the commentaries of the great practitioners. Accordingly, the entrance into practice is taught a little differently. However, all are the same in that they lead to the final attainment of the state of Vajradhara.

Notes

1. For details of the concentrations and the formless absorptions, see Lati Rinbochay & Denma Lochö Rinbochay. Meditative States in Tibetan Buddhism. Translated by Leah Zahler & Jeffrey Hopkins. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1997. [Return to text]