|

Dr. Gareth Sparham, PhD, is a graduate of Kopan Meditation Courses 3 and 4 and the Institute of Buddhist Dialectics, Dharamsala. He spent the summer of 1973 at Lawudo Monastery, Solu Khumbu, Nepal, and was moved to pen the following piece on the attributes of that Himalayan staple, tsampa. |

What is tsampa? It is grain first roasted until it pops and then ground into flour.

And who first thought of eating food in this way? I do not know nor really care to research the question, but now it is eaten by those people who live in the highest reaches of the Himalayas—Sherpas, Tibetans and the like.

The benefits of eating tsampa maybe immeasurable. I cannot say with real certainty what is the cause of the clear-headedness of the Himalayan Buddhist monks, of their great understanding and peace of mind, but it is of some interest perhaps that their basic food is tsampa. I have, what’s more, been told that when in retreat—deep meditation from which come peace and understanding—Buddhist yogis eat only tsampa one time a day.

From the Western view of excellence at this time of less attachment to wishful thinking and more attention to scientific veracity, tsampa would fare well on a nutritionist’s chart. The total time of cooking tsampa is about ten seconds. I’m sure, therefore, that all the good properties of the grain are kept.

It is, as may easily be seen, a most practical food. It can be kept like flour, yet is an instant comestible. Added to anything, it thickens it; it makes soup of tea, cakes of water, bread of your mouth. I hope some people will care to make some tsampa and eat it. In doing so, in eating as the great monks of the Himalayas eat, perhaps their attitude to life will improve and they will develop within themselves great love for all beings.

In making tsampa, the first step is purchase of the grain. Perhaps only because it is a hardy grain, able to withstand Tibet’s mountainous climate, barley was the usual grain used for tsampa. However, in Khumbu (the Mount Everest district of Nepal inhabited by Sherpas—Tibetans, who left Tibet hundreds of years ago), corn, wheat, millet and barley are made into tsampa. The process, with some small deviation, is the same in the preparation of each grain. In the West, perhaps natural food shops would have a good grains, and you could experiment to see which best suits your taste and temperament.

Having purchased the grain, the basic steps are: (1) drying, (2) roasting, and (3) grinding.

With barley, an additional process is added. The grain is first soaked in hot water for about half an hour. The water should be hot, and about one quart of water is poured over three quarters of a bucket of barley. The grain is mixed around with the hands so that each grain is covered with water. After about half an hour, the excess water is poured off and the grain left to sit overnight. This is not done with any other grain. I am not sure exactly why it is done this way.

All grains, with the exception of corn, which does not need it, are spread out on blankets to dry in the sun. A good day’s drying is sufficient.

The real work in making tsampa is in the roasting. The ancient way of the Himalayas, which ensures quick but ample cooking of the grain, requires the following things: (1) a constantly hot fire; (2) a wok or very big but manageable frying pan; (3) enough fine sand to fill the pan a quarter full; and (4) a sieve big enough to hold the sand and about a quart of grain. Equipped with these implements, you can roast to perfection!

Basically, the idea is to make the grain pop (like popcorn) as quickly as possible without burning it.

Put the sand into the wok and heat it up until very hot. Then pour on about one quart of grain (trying to rush it only makes it more difficult and may end up giving you very painful gas in the intestines). When the grain touches the sand and is mixed up in it, the popping starts. It should take no longer than 15 or 20 seconds to pop. If it does, the sand is not hot enough.

Pour the sand and popped grain into the sieve and shake it until only the grain is left. Put the sand back into the pan to reheat and the grain into a sack and continue in the same way until finished.

Grinding the tsampa is no problem here in Khumbu, as there are as many mills as streams. I think you can now buy grinders in the West (perhaps a health food store would either show you where to get one or help you find a place where you could use one).

Finally, some hints on eating tsampa from my personal viewpoint. I think you’ve got to go slow with tsampa. If you are hungry and want to get rid of that suffering of hunger quickly and without thought, tsampa is probably not as good as two or three peanut butter and jellies on Western white. A heaping bowl of tsampa with plenty of sugar and milk could catch on, but I think the gluey blandness of tsampa bolted down would turn most gluttons to different pastures.

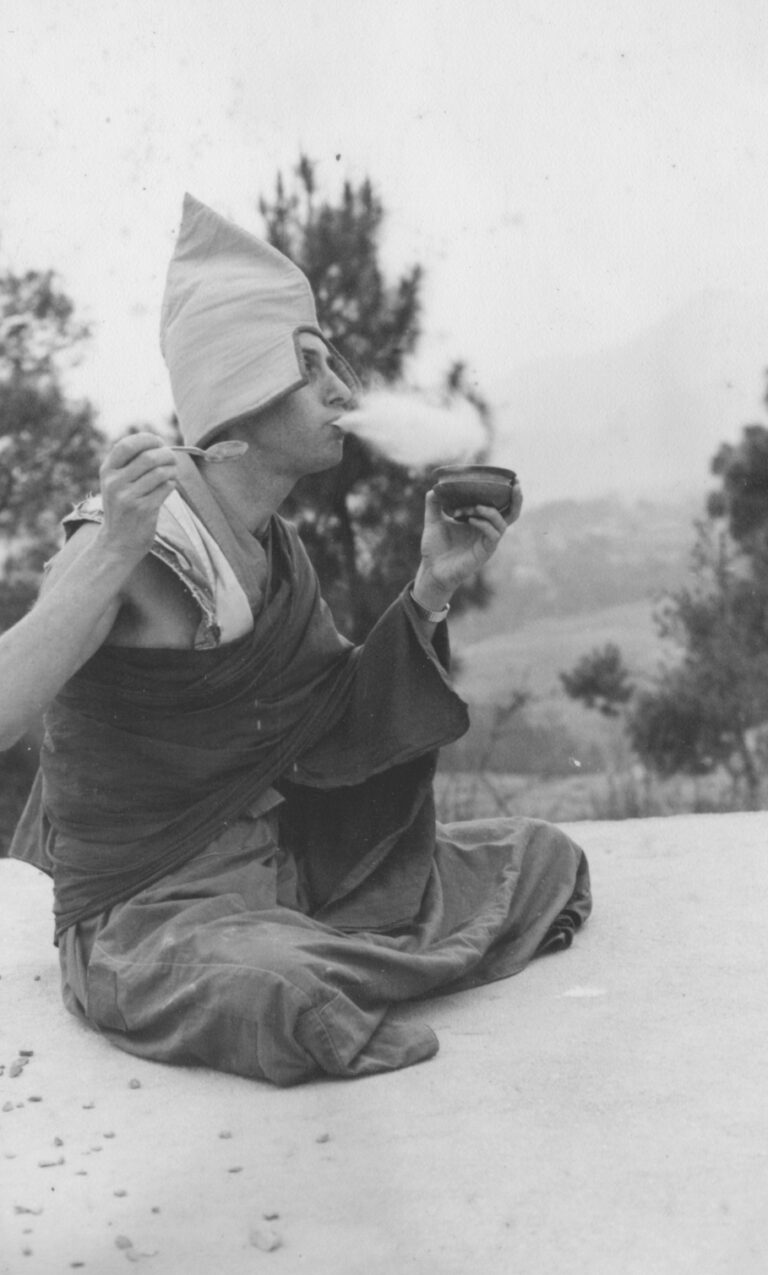

I have been told that the yogi’s way of eating tsampa is dry—without any liquid. Perhaps at first it would be strange: that watery cavern—into which flow the easily digestible milkshakes, the soft, spongy cakes, the mashed potatoes, the incredible hot apple pie with cheese or custard—being suddenly dried up. But it is all in the amount of time you are willing to take to eat. If you go slowly, it tastes very well, and you do not find yourself coughing out white clouds of dry flour from a parched throat.

Completely plain is the pure way to eat tsampa.

I usually put butter with it, which makes it a little easier to eat and more like Western food. I drink, coffee or tea at the same time. Many people here like to add sugar, especially to corn tsampa. It certainly makes it very palatable, but I can’t help thinking that the taste of the grain gets lost.

As I said, you can put it in anything. Monks used to carry around a bag of tsampa and make a quick meal with tea. I really couldn’t say how it would taste in a chocolate malted.