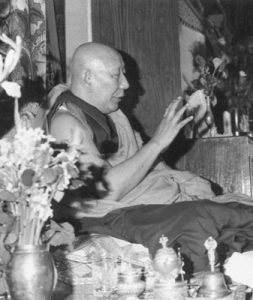

| This teaching was given at Tushita Mahayana Meditation Centre on November 14, 1979. Edited by Nicholas Ribush from an oral translation by Lama Gelek Rinpoche. First published in Teachings at Tushita, edited by Nicholas Ribush with Glenn H. Mullin, Mahayana Publications, New Delhi, 1981. Now appears in the 2005 LYWA publication Teachings From Tibet. |

Bodhicitta and wisdom

The enlightened attitude, bodhicitta, which has love and compassion as its basis, is the essential seed producing the attainment of buddhahood. Therefore, it is a subject that should be approached with the pure thought, “May I gain enlightenment in order to be of greatest benefit to the world.”

If we want to attain the state of the full enlightenment of buddhahood as opposed to the lesser enlightenment of an arhat, nirvana, our innermost practice must be cultivation of bodhicitta. If meditation on emptiness is our innermost practice, we run the risk of falling into nirvana instead of gaining buddhahood. This teaching is given in the saying, “When the father is bodhicitta and the mother is wisdom, the child joins the caste of the buddhas.” In ancient India, children of inter-caste marriages would adopt the caste of the father, regardless of the caste of the mother. Therefore, bodhicitta is like the father: if we cultivate bodhicitta, we enter the caste of the buddhas.

Although bodhicitta is the principal cause of buddhahood, bodhicitta as the father must unite with wisdom, or meditation on emptiness, as the mother in order to produce a child capable of attaining buddhahood. One without the other does not bring full enlightenment—even though bodhicitta is the essential energy that produces buddhahood, throughout the stages of its development it should be combined with meditation on emptiness. In the Perfection of Wisdom Sutras, where the Buddha spoke most extensively on emptiness, we are constantly reminded to practice our meditation on emptiness within the context of bodhicitta.

However, the spiritual effects of receiving teachings on bodhicitta are quite limited if we lack a certain spiritual foundation. Consequently most teachers insist that we first cultivate various preliminary practices within ourselves before approaching this higher precept. If we want to go to university, we must first learn to read and write. Of course, while merely hearing about meditation on love, compassion and bodhicitta does leave a favorable imprint on our mental continuum, for the teaching to really produce a definite inner transformation, we first have to meditate extensively on preliminaries such as the perfect human rebirth, impermanence and death, the nature of karma and samsara, refuge and the higher trainings in ethics, meditation and wisdom.

What precisely is bodhicitta? It is the mind strongly characterized by the aspiration, “For the sake of all sentient beings I must attain the state of full enlightenment.” While it’s easy to repeat these words to ourselves, bodhicitta is much deeper than that. It is a quality we cultivate systematically within our mind. Merely holding the thought “I must attain enlightenment for the sake of benefiting others” in mind without first cultivating its prerequisite causes, stages and basic foundations will not give birth to bodhicitta. For this reason, the venerable Atisha once asked, “Do you know anybody with bodhicitta not born from meditation on love and compassion?”

The benefits of bodhicitta

What are the benefits of generating bodhicitta? If we know the qualities of good food, we’ll attempt to obtain, prepare and eat it. Similarly, when we hear of the great qualities of bodhicitta we’ll seek to learn the methods and practices for generating it.

The immediate benefit of generating bodhicitta within our mind-stream is that we enter the great vehicle leading to buddhahood and gain the title of bodhisattva, a child of the buddhas. It does not matter what we look like, how we dress, how wealthy or powerful we are, whether or not we have clairvoyance or miraculous powers, or how learned we are, as soon as we generate bodhicitta we become bodhisattvas; regardless of our other qualities, if we do not have bodhicitta we are not bodhisattvas. Even a being with bodhicitta who takes rebirth in an animal body is respected by all the buddhas as a bodhisattva.

The great sages of the lesser vehicle possess numberless wonderful qualities but in terms of nature, a person who has developed even the initial stages of bodhicitta surpasses them. This is similar to the way that the baby son of a universal monarch who, although only an infant possessing no qualities of knowledge or power, is accorded higher status than any scholar or minister in the realm.

In terms of conventional benefit, all the happiness and goodness that exists comes from bodhicitta. Buddhas are born from bodhisattvas but bodhisattvas come from bodhicitta. As a result of the birth of buddhas and bodhisattvas, great waves of enlightened energy spread throughout the universe, influencing sentient beings to create positive karma. This positive karma in turn brings them much benefit and happiness. On the one hand, the mighty stream of enlightened and enlightening energy issues from the wisdom body of the buddhas, but since the buddhas are born from bodhisattvas and bodhisattvas from bodhicitta, the ultimate source of universal goodness and happiness is bodhicitta itself.

How to develop bodhicitta

How do we develop bodhicitta? There are two major methods. The first of these, the six causes and one effect, applies six causal meditations—recognizing that all sentient beings were once our own mother, a mother’s kindness, repaying such kindness, love, compassion and the extraordinary thought of universal responsibility—to produce one result: bodhicitta. The second technique is the meditation in which we directly change self-cherishing into the cherishing of others.

In order to practice either of these methods of developing bodhicitta we must first develop a sense of equanimity towards all living beings. [See Lama Zopa Rinpoche's Equilibrium Meditation.] We must transcend seeing some beings as close friends, others as disliked or hated enemies and the rest as merely unknown strangers. Until we have developed equanimity for all beings, any meditation we do in an attempt to develop bodhicitta will not be effective. For example, if we want to paint a mural on a wall we must first get rid of all the cracks and lumps on its surface. Similarly, we cannot create the beautiful bodhicitta within our mind until it has been purified of the distortions of seeing others as friend, enemy or stranger.

The attitude of discrimination

The way we impute this discrimination upon others is quite automatic and, as a result, whenever we see somebody we have labeled “friend,” attachment arises and we respond with warmth and kindness. Why have we labeled this person “friend”? It is only because on some level or other this person has benefited or supported us. Alternatively, whenever we encounter somebody we have labeled “enemy,” aversion arises and we respond with coldness and anger. The reason is again because that person once harmed or threatened us in some way. Similarly, when we encounter somebody who has neither helped nor harmed us, we apply the label “stranger” and have no feelings for that person one way or the other.

However, if we examine this method of discriminating others we will quickly see that it is an extremely unstable process. Even in this life, people once regarded as friends become enemies and enemies often become friends. And in the countless lives we have taken since beginningless time while spinning on the wheel of life there is not one sentient being who has consistently been either friend or enemy.

Our best friend of this life could easily have been our worst enemy in a previous incarnation and vice versa. A friend who mistreats us quickly becomes an enemy and an enemy who helps us soon becomes a new-found friend. So which one is really the friend and which one the enemy? Instead of responding to others on the basis of the ephemeral benefit or harm they bring us we should meditate that all have alternately benefited and harmed us in the stream of our infinite past lives and, in that way, abandon superficial discriminations.

A root cause of this discriminating mind is the self-cherishing attitude, the thought that makes us consider ourselves more important than others. As a result of self-cherishing we develop attachment to those who help us and aversion to those who cause us problems. This, in turn, causes us to create countless negative karmas trying to support the “helpers” and overcome the “harmers.” Thus we bring great suffering upon ourselves and others, both immediately and in future lives, as the karmic seeds of these actions ripen into suffering experiences.

The benefits of cherishing others

A teaching says, “All happiness in the world arises from cherishing others; every suffering arises from self-cherishing.” Why is this so? From self-cherishing comes the wish to further oneself even at others’ expense. This causes all the killing, stealing, intolerance and so forth that we see around us. As well as destroying happiness in this life, these negative activities plant karmic seeds for a future rebirth in the miserable realms of existence—the hell, hungry ghost and animal realms. Self-cherishing is responsible for every conflict from family problems to international wars and for all the negative karma thus created.

What are the results of cherishing others? If we cherish others, we won’t harm or kill them—this is conducive to our own long life. When we cherish others, we’re open to and empathetic with them and live in generosity—this is a karmic cause of our own future prosperity. If we cherish others, even when somebody harms or makes problems for us, we are able to abide in love and patience—a karmic cause of a beautiful form in future lives. In short, every auspicious condition arises from the positive karma generated by cherishing others. These conditions themselves bring joy and happiness and, in addition, act as causes for the attainment of nirvana and buddhahood.

How? To attain nirvana we have to master the three higher trainings in moral discipline, meditation and wisdom. Of these, the first is the most important because it is the basis for the development of the other two. The essence of moral discipline is abandoning any action that harms others. If we cherish others more than ourselves we will not find this discipline difficult. Our mind will be calm and peaceful, which is conducive to both meditation and wisdom.

Looking at it another way, cherishing others is the proper and noble approach to take. In this life, everything that comes to us is directly or indirectly due to the kindness of others. We buy food from others in the market; the clothing we wear and the houses we live in depend upon the help of others. And to attain the ultimate goals of nirvana and buddhahood, we are completely dependent upon others; without them we would be unable to meditate upon love, compassion, trust and so forth and thus could not generate spiritual experiences.

Also, any meditation teaching we receive has come from the Buddha through the kindness of sentient beings. The Buddha taught only to benefit sentient beings; if there were no sentient beings he would not have taught. Therefore, in the Bodhicaryavatara, Shantideva comments that in terms of kindness, sentient beings are equal to the buddhas. Sometimes, mistakenly, people have respect and devotion for the buddhas but dislike sentient beings. We should appreciate sentient beings as deeply as we do the buddhas themselves.

If we look at happiness and harmony we will find its cause to be universal caring. The cause of unhappiness and disharmony is the self-cherishing attitude.

At one time the Buddha was an ordinary person like us. Then he abandoned self-cherishing and replaced it with universal caring and entered the path to buddhahood. Because we still cling to the self-cherishing mind, we are left behind in samsara, benefiting neither ourselves nor others.

One of the Jataka Tales—accounts of the Buddha’s previous lives—tells the story of an incarnation in which the Buddha was a huge turtle that took pity on some shipwreck victims and carried them to shore on its back. Once ashore, the exhausted turtle fell into a faint but as he slept he was attacked by thousands of ants. Soon the biting of the ants woke the turtle up, but he saw that if he were to move, he would kill innumerable creatures. Therefore, he remained still and offered his body to the insects as food. This is the depth to which the Buddha cherished living beings. Many of the Jataka Tales tell similar stories of the Buddha’s previous lives in which he showed the importance of cherishing others. The Wish-Fulfilling Tree contains 108 such stories.

Essentially, self-cherishing is the cause of every undesirable experience and universal caring is the cause of every happiness. The sufferings of both the lower and upper realms of existence, all interferences to spiritual practice and even the subtle limitations of nirvana come from self-cherishing, while every happiness of this and future lives comes from cherishing others.

Engaging in bodhicitta

Therefore, we should contemplate deeply the benefits of cherishing others and try to develop an open, loving attitude towards all living beings. This should not be an inert emotion but one characterized by great compassion—the wish to separate others from their suffering. Whenever we encounter a being in suffering we should react like a mother witnessing her only child caught in a fire or fallen into a terrible river; our main thought should be to help others. With respect to those in states of suffering, we should think, “May I help separate them from their suffering,” and those in states of happiness, we should think, “May I help them maintain their happiness.” This attitude should be directed equally towards all beings. Some people feel great compassion for friends or relatives in trouble but none for unpleasant people or enemies. This is not spiritual compassion; it is merely a form of attachment. True compassion does not discriminate between beings; it regards all equally.

Similarly, true love is the desire to maintain the happiness of all beings impartially, regardless of whether we like them or not. Spiritual love is of two main types: that merely possessing equanimity and that possessing the active wish to maintain others’ happiness. When we meditate repeatedly on how all beings have in previous lives been mother, father and friend to us, we soon come to have equanimity towards them all. Eventually this develops into an overwhelming wish to see all beings possess happiness and the causes of happiness. This is great, undiscriminating love.

By meditating properly on love and compassion we produce what are called the eight great benefits. These condense into two: happiness in this and future lives for both ourselves and others and development along the path to full and perfect buddhahood. Such meditation results in rebirth in the three upper realms as a human or a god and fertilizes the seeds of enlightenment.

In brief, we should have the wish to help others maintain their happiness and separate them from suffering regardless of whether they have acted as friend or enemy to us. Moreover, we should develop a personal sense of responsibility for their happiness. This is called the “special” or “higher” thought and is marked by a strong sense of responsibility for the welfare of others. It is like taking the responsibility of going to the market to get somebody exactly what he needs instead of just sitting reflecting on how nice it would be if he had what he wanted. We take upon ourselves the responsibility of actually fulfilling others’ requirements.

Then we should ask ourselves, “Do I have the ability to benefit all others?” Obviously we do not. Who has such ability? Only an enlightened being, a buddha, has the ability to benefit others to the full. Why? Because only those who have attained buddhahood are fully developed and fully separated from limitations; those still in samsara cannot place others in nirvana. Even shravaka arhats or tenth level bodhisattvas are unable to benefit others fully, for they themselves still have limitations, but buddhas spontaneously and automatically benefit all beings with every breath they take. The enlightened state is metaphorically likened to the drum of Brahma, which automatically booms teachings to the world, or to a cloud, which spontaneously makes cooling shade and life-giving water wherever it goes.

To fulfill others’ needs, we should seek to place them in the total peace and maturity of buddhahood; to be able to do this we must first gain buddhahood ourselves. The state of buddhahood is an evolutionary result of bodhicitta. Bodhicitta is born from the special thought of universal responsibility—the thought of benefiting others by oneself alone. To drink water we must have both the desire to drink and a container for the water. The wish to benefit others by placing them in buddhahood is like the desire to drink and the wish to attain enlightenment oneself in order to benefit them in this way is like the container. When both are present, we benefit ourselves and others.

If we hear of the meditations that generate bodhicitta and try to practice them without first refining our minds with the preliminary meditations, it is very unlikely that we shall make much inner progress. For example, if we meditate on compassion without first gaining some experience of the meditations on the four noble truths, or at least on the truth of suffering, we will develop merely a superficial understanding. How can we experience mature compassion, the aspiration to free all beings from suffering, when we do not know the deeper levels of suffering that permeate the human psyche? How can we relate to others’ suffering when we do not even know the subtle levels of frustration and tension pervading our own being? In order to know the workings of our own mind, we have to know every aspect of suffering; only then can we be in a position to empathize with the hearts and minds of others. We must have compassion for ourselves before we can have it for others.

Through meditation on suffering, we can generate a certain amount of renunciation, or spiritual stability. This stability should be guarded and cultivated by the various methods taught on the initial and intermediate stages of training, which are the two main steps in approaching the meditations on bodhicitta. As we progress in our meditations on the suffering nature of being and the causes of this suffering, we begin to search for the path leading to transcendence of imperfection. We meditate upon the precious nature and unique opportunities of human existence, which makes us appreciate our situation. We then meditate upon impermanence and death, which helps us transcend grasping at the petty aspects of life and directs our mind to search for spiritual knowledge.

Because spiritual knowledge is not gained from books or without cause, its cause must be cultivated. This means training properly under a fully qualified spiritual master and generating the practices as instructed.

Merely hearing about bodhicitta is very beneficial because it provides a seed for the development of the enlightened spirit. However, cultivation of this seed to fruition requires careful practice. We must progress through the actual inner experiences of the above-mentioned meditations, and for this we require close contact with a meditation teacher able to supervise and guide our evolution. In order for our teacher’s presence to be of maximum benefit, we should learn the correct attitudes and actions for cultivating an effective guru-disciple relationship. Then, step-by-step, the seeds of bodhicitta our teacher plants within us can grow to full maturity and unfold the lotus of enlightenment within us.

This is only a brief description of bodhicitta and the methods of developing it. If it inspires an interest in this topic within you, I’ll be very happy. The basis of bodhicitta—love and compassion—is a force that brings every benefit to both yourself and others, and if this can be transformed into bodhicitta itself, your every action will become a cause of omniscient buddhahood. Even if you can practice to the point of simply slightly weakening your self-cherishing attitude, I’ll be very grateful. Without first generating bodhicitta, buddhahood is completely out of the question; once bodhicitta has started to grow, perfect enlightenment is only a matter of time.

You should try to meditate regularly on death and impermanence and thus become a spiritual practitioner of initial scope. Then you should develop the meditations on the unsatisfactory nature of samsara and the three higher trainings [ethics, concentration and wisdom] and thus become a practitioner of medium scope. Finally, you should give birth to love, compassion, universal responsibility and bodhicitta and thus enter the path of the practitioner of great scope, the Mahayana, which has full buddhahood as its goal. Relying on the guidance of a spiritual master, you should cultivate the seeds of bodhicitta in connection with the wisdom of emptiness and, for the sake of all that lives, quickly actualize buddhahood. This may not be an easy task, but it has ultimate perfection as its fruit.

The most important step in spiritual growth is the first: the decision to avoid evil and cultivate goodness within your stream of being. On the basis of this fundamental discipline, every spiritual quality becomes possible, even the eventual perfection of buddhahood.

Each of us has the potential to do this; each of us can become a perfect being. All we have to do is direct our energy towards learning and then enthusiastically practice the teachings. As bodhicitta is the very essence of all the Buddha’s teachings, we should make every effort to realize it.