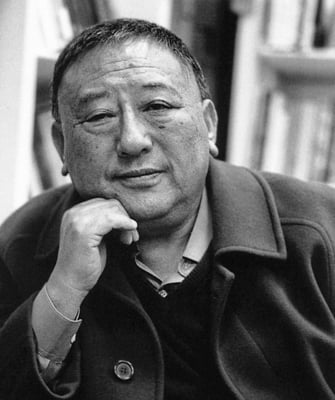

| Gehlek Rinpoche (1939—2017) was born in Tibet and studied at Drepung Monastery and later in India, where he gained his lharampa geshe degree. After publishing many important texts and teaching Dharma in India, in the 1980s he came to the USA, where, based in Ann Arbor, Michigan, he is now spiritual head of the Jewel Heart Buddhist centers in America and abroad.This teaching was given at Tushita Mahayana Meditation Centre on 25 April 1980. First published in Teachings at Tushita, edited by Nicholas Ribush with Glenn H. Mullin, Mahayana Publications, New Delhi, 1981. Now appears in the 2005 LYWA publication Teachings From Tibet. |

Lama Tsongkhapa taught that we should practice both contemplative meditation and concentration meditation. In the former we investigate the object of meditation by contemplating it in all its details; in the latter we focus single-pointedly on one aspect of the object and hold our mind on it without movement.

Single-pointed concentration [samadhi] is a meditative power that is useful in either of these two types of meditation. However, in order to develop samadhi itself we must cultivate principally concentration meditation. In terms of practice, this means that we must choose an object of concentration and then meditate single-pointedly on it every day until the power of samadhi is attained.

The five great obstacles to samadhi are laziness; forgetfulness; mental wandering and depression; failure to correct any of the above problems when they arise; and applying meditative opponents to problems that are not there, that is, they are purely imaginary.

Laziness

The actual antidote to laziness is an initial experience of the pleasure and harmony of body and mind that arise from meditation. Once we experience this joy, meditation automatically becomes one of our favorite activities. However, until we get to this point we must settle for a lesser antidote to laziness—something that will counteract our laziness and encourage us to practice until the experience of meditative ecstasy comes to us. This lesser antidote is contemplation of the benefits of samadhi.

What are these benefits? Among them are attaining siddhis very quickly, transforming sleep into profound meditation and being able to read others’ minds, see into the future, remember past incarnations and perform magical acts such as flying and levitating. Contemplating these benefits helps eliminate laziness.

Forgetfulness

The second obstacle to samadhi is forgetfulness—simply losing awareness of the object of meditation. When this happens, concentration is no longer present. Nagarjuna illustrated the process of developing concentration by likening the mind to an elephant to be tied by the rope of memory to the pillar of the object of meditation. The meditator also carries the iron hook of wisdom with which to spur on the lazy elephant.

What should we choose as an object of meditation? It can be anything—a stone, fire, a piece of wood, a table and so forth—as long as it does not cause delusions such as desire or aversion to arise. We should also avoid an object that has no qualities specifically significant to our spiritual path. Some teachers have said that we should begin with fire and later change to swirling clouds and so forth but this is not an effective approach. Choose one object and stick to it.

Many people choose the symbolic form of a buddha or a meditational deity as their object. The former has many benefits and is a great blessing; the latter provides a special preparation for higher tantric practice. In the beginning we can place a statue or painting of the object of meditation in front of us and look at it as we concentrate. But as it is our mind, not our eyes, that we want to develop, this should be done only until familiarity with the object is gained. The most important point is to settle on one object and not change it. There are stories of great saints who chose the form of a yak as their object but generally it is better to select an object of greater spiritual value and not change it until at least the first of the four levels of samadhi is attained.

Consistency in practice is also important. Once we begin we should continue every day until we reach our goal. If the conditions are perfect, we can do this in three months or so. But practicing an hour a day for a month and then missing a day or two will result in minimal progress. Constant, steady effort is necessary. We need to follow a fixed daily schedule of meditation.

Let’s say our object of concentration is the symbolic form of the Buddha. The first problem is that we cannot immediately visualize the form clearly. The advice is this: don’t be concerned with details—just get a sort of yellowish blur and hold it in mind. At this stage you can use an external image as an aid, alternating between looking at the object and then trying to hold it in mind for a few moments without looking. Forgetfulness, the second of the five obstacles, is very strong at this point and we must struggle against it. Get a mental picture of the object and then hold it firmly. Whenever it fades away, forcefully bring it back.

Wandering and depression

This forceful holding of the object gives rise to the third problem. When we try to hold the object in the mind, the tension of this effort can produce either agitation or depression. The forced concentration produces a heaviness of mind and this in turn leads to sleep, which itself is a coarse form of depression. The subtle form of depression is experienced when we are able to hold the object in mind for a prolonged period of time but without any real clarity. Without clarity, the meditation lacks strength.

To illustrate this with an example: when a man in love thinks of his beloved, her face immediately appears radiantly in his mind and effortlessly remains with clarity. A few months later, however, when they are in the middle of a fight, he has to strain to think of her in the same way. When he had the tightness of desire the image was easy to retain clearly. This tightness is called close placement [Tib: nyer-zhag; Skt: satipatthana]. When close placement is lost, the image eventually disappears and subtle depression sets in. It is very difficult to distinguish between proper meditation and meditation characterized by subtle depression, but remaining absorbed in the latter can create many problems.

We must also guard against the second problem, mentally wandering away from the object of meditation. Most people sit down to concentrate on an object but their mind quickly drifts away to thoughts of the day’s activities, a movie or television program they recently saw or something like that.

Pabongka Rinpoche, the root guru of both tutors of the present Dalai Lama, used to tell the story of a very important Tibetan government official who would always put a pen and a notebook beside his meditation seat whenever he did his daily practices, saying that his best ideas came from mental wandering in meditation.

Our mind wanders off on some memory or plan and we don’t even realize that it’s happening. We think we are still meditating but suddenly realize that for the past thirty minutes our mind has been somewhere else. This is the coarse level of wandering mind. When we have overcome this we still have to deal with subtle wandering, in which one factor of the mind holds the object clearly but another factor drifts away. We have to develop the ability of using the main part of our mind to concentrate on the object and another part to watch that the meditation is progressing correctly. This side part of the mind is like a secret agent and without it we can become absorbed in incorrect meditation for hours without knowing what we are doing—the thief of mental wandering or depression comes in and steals away our meditation.

We have to watch, but not over-watch. Over-watching can create another problem. It is like when we hold a glass of water: we have to hold it, hold it tightly, and also watch to see that we are holding it correctly and steadily without allowing any water to spill out. Holding, holding tightly and watching: these are the three keys of samadhi meditation.

Failure to correct problems

The fourth problem is failure to correct problems such as depression or wandering. The antidote to depression is tightening the concentration; the antidote to wandering is loosening it.

When counteracting depression with tightness, we must be careful to avoid the excessive tightness that a lack of natural desire to meditate can create; we have to balance tightness with relaxation. When our mind gets too tight like this we should just relax within our meditation. If that doesn’t work, we can forget the object for a while and concentrate on happy thoughts, such as the beneficial effects of bodhicitta, until our mind regains its composure, and then return to our object of meditation. This is akin to washing our face in cold water.

If contemplating a happy subject does not pick us up, we can visualize that our mind takes the form of a tiny seed at our heart and then shoot this seed out of the crown of our head into the clouds above, leave it there for a few moments and then bring it back. If this doesn’t help, we can just take a short break from our meditation.

Similarly, when mental wandering arises, we can think of an unpleasant subject, such as the suffering nature of samsara.

When our mind is low, changing to a happy subject can bring it back up; when it’s wandering, changing to an unpleasant subject can bring it down out of the sky and back to earth.

Correcting non-existent problems

The fifth obstacle is applying antidotes to depression or wandering that are not present or overly watching for problems. This hinders the development of our meditation.

The meditation posture

The posture we recommend for meditation is the seven-point posture of Buddha Vairochana. Sit on a comfortable cushion in the vajra posture with both legs crossed and your soles upturned. Indians call this the lotus posture; Tibetans call it the vajra posture. It is the first of the seven features of the Vairochana posture. If you find this or any of the other points difficult, simply sit as is most convenient and comfortable.

The seven-point posture is actually the most effective position for meditation once you develop familiarity and comfort with it, but until then, if one of the points is too difficult you can substitute it with something more within your reach.

Keep your back straight and tilt your head slightly forward with your eyes cast down along the line of your nose. If your eyes are cast too high, mental wandering is facilitated; if too low, sleepiness or depression too easily set in. Don’t close your eyes but look down along the line of your nose to an imaginary point about five feet in front of you. In order not to be distracted by environmental objects, many meditators sit facing a blank wall. Keep your shoulders level, your teeth lightly closed and place the tip of the tongue against the front of your hard palate just behind your top teeth, which will prevent you from getting thirsty when engaging in prolonged meditation.

The meditation session

Start your meditation session with a prayer to the lineage gurus in connection with your visualization. Then go directly to concentrating on your chosen object, such as an image of the Buddha.

At first, your main difficulty will be to get hold of the mental image; even getting a blurred image is difficult. However, you have to persist.

Once you have succeeded, you have to cultivate clarity and the correct level of tightness, while guarding against problems such as wandering, depression and so forth. Just sit and pursue the meditation while watching for distortions. Sometimes the object becomes too clear and you break into mental wandering; at other times it becomes dull and you lose it to sleep or torpor. In this way, using the six powers and the four connecting principles,1 you can overcome the five obstacles and ascend the nine stages to calm abiding, where you can meditate effortlessly and ecstatically for as long as you want.

In the beginning, your main struggle will be against wandering and depression. Just look for the object and as soon as you notice a problem, correct it. On the ninth stage, even though you can concentrate effortlessly for a great length of time, you have not yet attained samadhi. First you must also develop a certain sense of pleasure and harmony within both body and mind. Concentrate until a great pleasure begins to arise within your head and spreads down, feeling like the gentle invigorating warmth of a hot towel held against your face. The pleasure spreads throughout your body until you feel as light as cotton. Meditate within this physical pleasure, which gives rise to mental ecstasy. Then when you meditate you have a sense of inseparability with the object—your body seems to disappear in meditation and you sort of become one with the object; you almost want to fly away in your meditation. After this you can fix your mind on any object of virtue for as long you want. This is the preparatory stage, or the first level of samadhi. Meditation is light and free, like a humming bird in mid-air drinking honey from a red flower.

Beyond this you can either remain in samadhi meditation and cultivate the four levels of samadhi or, as advised by Lama Tsongkhapa, turn to searching for the root of samsara. No matter how high your samadhi, if you do not cut the root of samsara, you will eventually fall.

Lama Tsongkhapa likened samadhi to a horse ridden by a warrior and the wisdom that cuts the root of samsara to the warrior’s sword. When you have gained the first level of samadhi you have found the horse and can then turn to the sword of wisdom. Unless you gain the sword of wisdom your attainment of samadhi will be prone to collapse. You can take rebirth in one of the seventeen realms of the gods of form but eventually you will fall. On the other hand, if you develop basic samadhi and then apply it to the development of wisdom you’ll be able to cut the root of samsara as quickly as a crow takes out the eyes of an enemy. Once you’ve cut this root, you are beyond falling.

Notes

1. See His Holiness the Dalai Lama's Opening the Eye of New Awareness, pp.53-66.